Published June 24, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated June 24, 2015 at 10:04 a.m.

In the summer of 1960, Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb, then 72, intended to expand her collection of American folk art to include modern painting. Galleries had loaned her about 10 works by Andrew Wyeth, Charles Sheeler, Georgia O'Keeffe, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and William Zorach for consideration. Notes and a list Webb prepared indicate her interest in a dozen more artists. But when she died in November of that year, all but one of the paintings — Wyeth's "Soaring" — were returned.

Had Webb lived to exhibit these works, the show might have looked a bit like the one now on view at the museum: "American Moderns, 1910-1960: From O'Keeffe to Rockwell." Created by the Brooklyn Museum from its collection, the exhibit has traveled to eight other museums around the country, but its connection with its last stop may be unique.

"This is the collection that never happened," quips museum director Tom Denenberg. Indeed, among the exhibit's 44 paintings and three sculptures are three paintings by O'Keeffe and one each by Kuniyoshi, N.C. Wyeth — Andrew's father — and Marguerite Thompson Zorach, who was William Zorach's wife, Denenberg points out.

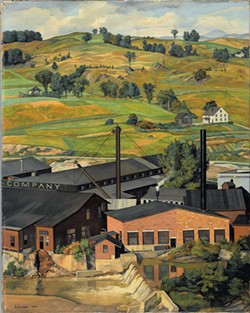

One painting in the show, a Vermont scene, has an even closer connection with Webb. "A Barre Granite Shed" (1931), by Luigi Lucioni, was given to the Brooklyn Museum by Mrs. Horace Havemeyer, likely the wife of Webb's brother. Webb met the New York-based Italian American painter in 1930 and invited him to summer at her estate. He spent the rest of his summers in Vermont, eventually on a farm near Manchester. The Shelburne Museum collection includes a Lucioni still life he gifted to the Webb family.

Such local associations aside, "American Moderns" will fascinate any viewers expecting to find a typical representation of modernism. As Denenberg puts it, until a decade ago, the "received wisdom" in the art-history world was that modernism in the U.S. leapt "from the Armory Show to Jackson Pollock." That is, "modern" art allegedly encompassed only European avant-garde movements such as cubism, first introduced to Americans in the 1913 Armory Show in New York City; and abstract expressionism, a movement of the 1940s through the early '60s.

By contrast, "this material" — Denenberg gestures toward the gallery walls — "was overlooked, or looked down upon, sometimes because of its association with the WPA [the federal Works Progress Administration]." The leftist leanings of Rockwell Kent (1882-1971), for example, contributed to his obscurity. The painter served as president of the communist-affiliated International Workers Order and, late in life, donated hundreds of his paintings to the Soviet Union. Fortunately, Kent's "Down to the Sea," which is among this exhibit's most arresting paintings, was not one of them.

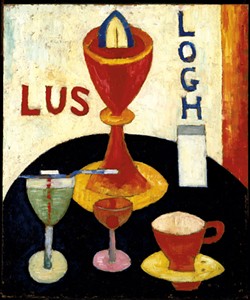

The thematically grouped show does begin with "Cubist Experiments," one of six categories organizing "American Moderns." Echoes of Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Braque abound in this first section. Albert Gallatin's "Composition" (1937), an architectural assemblage of flat shapes hinting at a guitar or violin, recalls Le Corbusier's paintings from the early 1920s. Max Weber's "The Cellist" (1917) channels Picasso's layered perspectives. Marsden Hartley's Fauve-hued "Handsome Drinks," with its inscrutable letters ("Lus, Logh") and title somewhere between arch and despairing, salutes Parisian café life. But it places a delicious-looking manhattan between an absinthe and a coffee. The First World War had just forced the artist's reluctant return to New York.

That city's streets and high-rises inspired many of the works grouped in "Modern Structures." Stuart Davis collaged together symbols of urban life — gas station, barber pole — in "Landscape With Clay Pipe" (1941). Its flat, cartoon-like shapes in unmodulated red, pink, teal and blue suggest Joan Miró's similarly elemental forms and colors. That lively painting contrasts vividly with George Ault's "Manhattan Mosaic," with its spare, geometric apartment buildings nearly blocking out a tiny square of sky.

A greater part of the exhibit, by contrast, is dedicated to images of nature. Denenberg points out that, while "people are getting bombarded with urban imagery in magazines" during this era, urban painters flocked to seaside and pastoral getaways in the summers. Maine's Monhegan Island was already an artists' colony when Kent painted "Down to the Sea" there. The large 1910 work depicting fishermen and their families interacting in small groups along the shoreline is a beautiful study in light and shadow à la Edward Hopper, who would paint on the island six years later.

That other master of light, Winslow Homer, is a direct influence on such scenes; both Kent and Hartley revered the 19th-century painter and his late-career depictions of the sea off coastal Maine. More iconic New England imagery appears in George Biddle's realistic "Giant Crab" (1941) and Hartley's "White Cod" (1942), featuring a ghostly pair of dead fish. Says Denenberg of this group of works, "They're creating a place for old New England in the modern world."

O'Keeffe painted "2 Yellow Leaves (Yellow Leaves)" in 1928, the year before she first visited New Mexico; it probably depicts the fall colors around Alfred Stieglitz's family home in Lake George, N.Y. (see related story on page 36). In a fascinating pairing, the show also gives us the reassemblage of those colors in the completely abstract "Green, Yellow and Orange," which O'Keeffe painted 32 years later.

Form rather than place concerns the artist in the later painting, and even in the earlier one, it's form that draws the eye. O'Keeffe's two aspen leaves, a smaller one atop a larger, slightly damaged one, hint at female and male forms and the transience of their pairing: Already dead, the leaves have been laid on a white surface.

"American Moderns" encompasses such a wide variety of form and subject matter that it sometimes seems as if the exhibit could include any work made in America during the 50 years of its range. A final section on "Americana," for instance, features the illustrator Norman Rockwell's "The Tattoo Artist" (1944) and a 1951 village winter scene by Grandma Moses, called "Early Skating." Denenberg explains, "Folk art is a modernist construction of the 1930s."

Moses' first show, in fact, occurred at the Museum of Modern Art in 1939. When the Shelburne Museum mounts a Grandma Moses exhibit next year, the director says, "our thesis is going to be that she's a modernist."

If the "modern" era is associated with new and radical change, then "American Moderns" as a whole may be more modern than any particular work in the show. Says Denenberg of the exhibit, "It's an attempt to broaden the concept of modernism. It adds a little breathing room to it."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Revisiting Modern"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Totality Towns: What to Do and See in the Path of the Eclipse

Apr 2, 2024 -

Shelburne: What to See, Do and Eat During the Eclipse

Feb 6, 2024 -

Apoc-eclipse Now: Scenes From an Eclipse Planning Meeting in Shelburne

Feb 5, 2024 -

Best outdoor music venue

Aug 2, 2023 -

Best large live music venue

Aug 2, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.