click to enlarge

- Amy Lilly

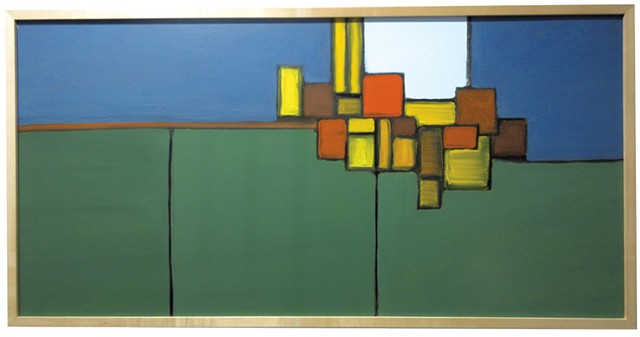

- "View of Lucca"

Ray Brown's exhibit at the Front in Montpelier will close on March 29, two weeks before his 80th birthday. Though currently recovering from heart and lung ailments in a rehab facility, Brown came out in a wheelchair last Friday to attend his opening. The show's title references the last volume of poetry by his friend David Budbill, who died in 2016.

If the title seems to suggest imminent mortality, though, the oil paintings are mainly focused on ways of seeing in the here and now. Most of the works explore landscapes and buildings, either as abstracted geometric forms or as semi-realistic forms reduced to their essentials. Three small works depicting a trio of vessels channel Giorgio Morandi; Brown's own varied collection of vessels shows up in six still lifes of flowers in bud vases.

This is the Front's first solo exhibition, inaugurating the collectively owned gallery's new plan to alternate monthly between group and solo exhibits. Hasso Ewing and Michelle Lesnak, two fellow gallery members, chose the paintings from among Brown's extensive output in his home studio while he was in rehab, according to his wife, Jody. The works date from 2008 to 2019 (more recent ones can be viewed around the corner at the Drawing Board, an art-supply and framing store the couple owned from 1983 to 2007). Yet they continue experiments with form that Brown began 60 years ago.

click to enlarge

- Amy Lilly

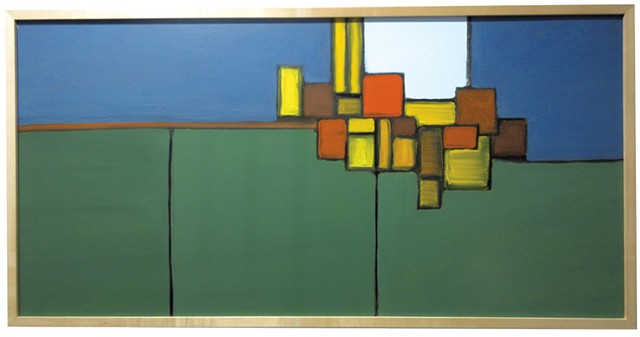

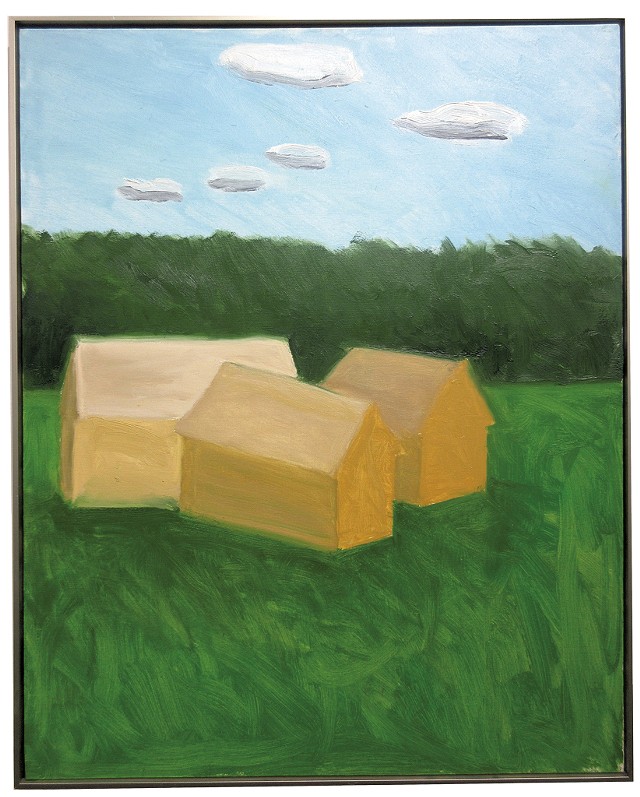

- "Ochre Buildings"

Born in Brookline, Mass., Brown attended the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston from 1959 to '63 — the height of abstract expressionism.

"I thought when I went to art school — and I was madly wrong about this — that I would learn to paint like the late 19th-century painters," Brown recalled by phone before the opening. Instead, he learned to imitate Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

In an interview that appears in the 2019 documentary Ray Brown: Portrait of an Artist, by Nat Winthrop (available on YouTube), Brown identifies his great leap forward as an artist: the moment when he thought to marry abstraction with landscape.

A series of Italian landscapes on view at the Front, made from sketches Brown did during five visits to that country, demonstrate his ongoing interest. "View of Lucca" depicts a cluster of heavily outlined rectilinear shapes set between a stepped green landscape and dark blue sky, both as geometrically rendered as the Tuscan town.

click to enlarge

- Pamela Polston

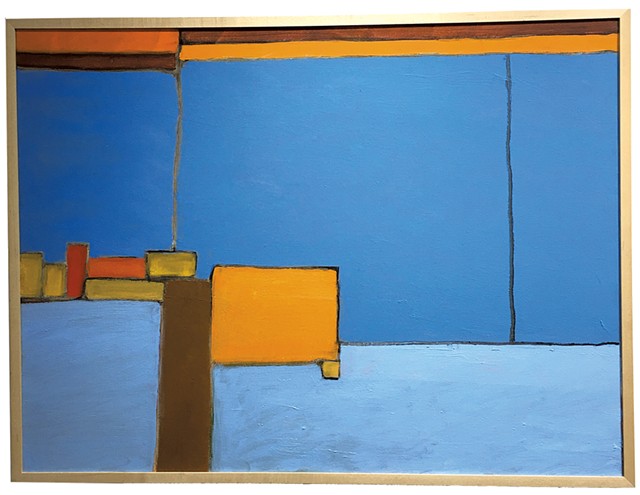

- "Tuscany Square"

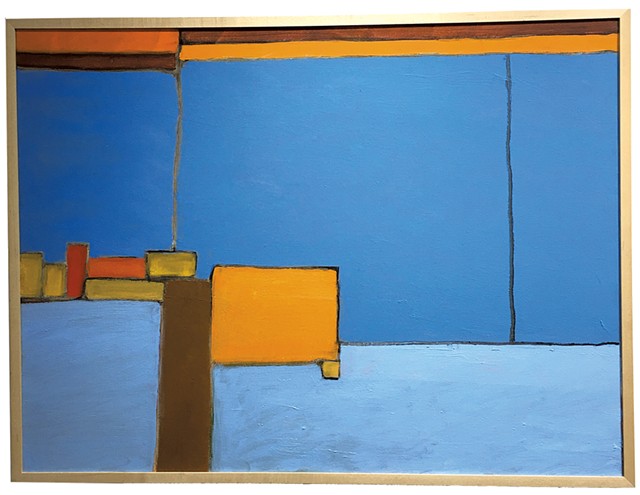

The similarly flat "Tuscany Square" and "Tuscany #4" pursue the same idea with more freedom, as do three "Assisi" paintings. In these, earth and blue sky — or perhaps water — appear merely as select blocks of color in compositions with many.

After college, Brown attended the storied Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where he found his "own style," he said. At the time, that meant religious paintings based on Bible scenes. He returned to the Boston area to teach in several schools and museums before moving to Vermont with Jody in the early 1980s.

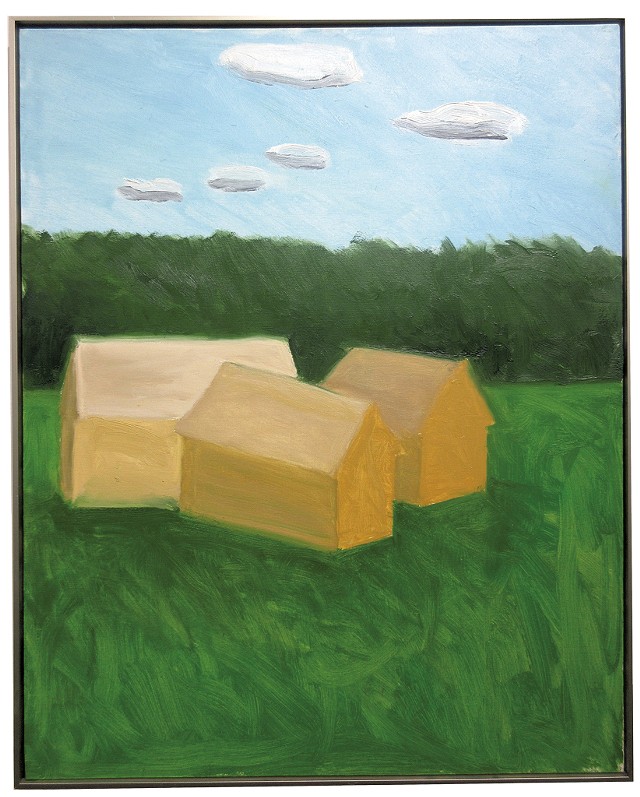

Brown has been painting Vermont's landscapes, barns and gabled houses ever since. Examples included in the exhibit seem to indicate a preference for a greater degree of realism when it comes to Green Mountain scenes. "Hardwick," "Hardwick II," "Grey Sky" and "Blue Sky" render the buildings as blocky forms in perspective. Some are set against a scrim of dark green forest, or include textured grass in the foreground or defined — if geometrically rendered — cloudscapes.

Perhaps the least realistic of these is "Ochre Buildings," if only because the monocolored trio of buildings has no recognizable arrangement — they look like cardboard cutouts — and the color is atypical for the area.

click to enlarge

- Pamela Polston

- "Three Villas"

Equally surprising color choices inform the four flat-perspective paintings titled "Newcomb's Forge #1," "Villa," "Two Villas" and "Three Villas." The first is an ode to the abstract forms of a friend's forge in Massachusetts, minus the expected black of that apparatus. It depicts two red rectangles with white tips extending toward each other from the top and bottom of a green background. In the villa paintings, blocks of yellow stand out among blocks of bright green and dark red.

In Winthrop's film, Brown says he discovered early on that he was color blind — or at least that he didn't "see colors the way other people saw them." He appears to have viewed this trait as an obstacle to overcome — an attitude the artist has brought to many challenges. At the age of 66, for example, Brown had a stroke that disabled the right side of his body. Over time, he taught himself to paint with his left hand.

When asked what drives him to start a painting, Brown replied, "the need to paint. I paint every day, or I read. Right now I'm reading a book about color."

Brown's exhibition at the Front may be a tumble toward the end, or it may simply be the determined continuation of a life's work.