Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

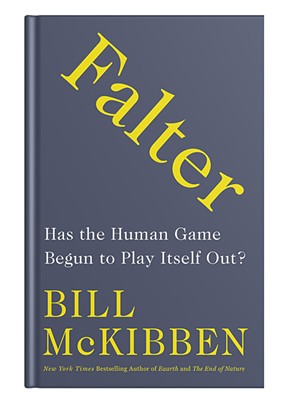

Book Review: 'Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?' by Bill McKibben

Published March 27, 2019 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated April 9, 2019 at 8:16 p.m.

Early in his writing career, recalls Bill McKibben in Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?, he "spent a year tracing every pipe and cable that entered and exited my Greenwich Village apartment." For his 1992 book The Age of Missing Information, he recorded everything that came across 100 channels of cable TV during a single day, then compared watching all of that with spending a day in the woods near his home.

Needless to say, he is thorough.

McKibben's new Falter is concerned with what he calls "the human game ... of culture and commerce and politics; of religion and sport and social life; of dance and music; of dinner and art and cancer and sex and Instagram; of love and loss; of everything that comprises the experience of our species." Characteristically, he begins by focusing on "the most mundane aspect of our civilization I can imagine": a roof.

In quick succession he considers where an asphalt shingle comes from, step by step, and invites the reader to "Marvel for a moment at the thousands of events that must synchronize for all this work ... the sheer amount of human organization..." By looking at the vast via the minuscule, McKibben places us in the midst of the modernity we've made, which is disrupting intricate equilibriums in the nonhuman world surrounding us.

Framed by the brief "Opening Note on Hope" and a contemplative epilogue, Falter has four parts: "The Size of the Board," "Leverage," "The Name of the Game" and "An Outside Chance." If McKibben had ended with part three, this would have been the scariest book this reviewer had ever read.

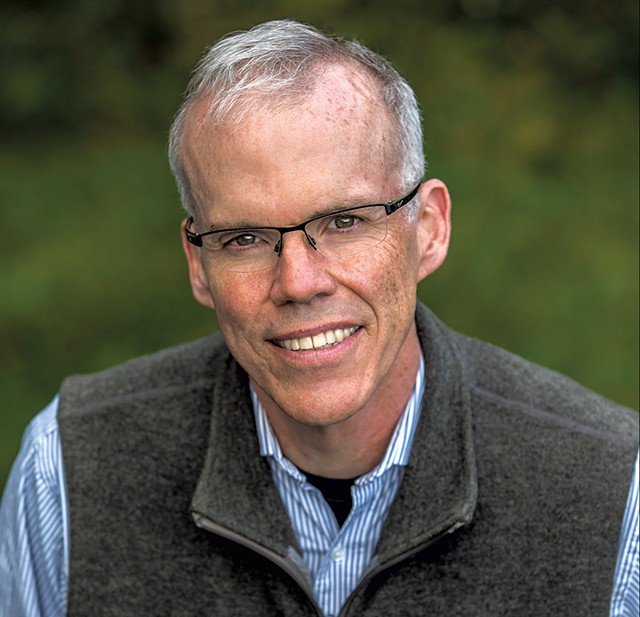

Yet clearly his aim isn't merely to scare. The Ripton resident, who has authored 17 previous books and hundreds of articles and essays, is essentially a teacher, currently the Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College.

Falter poses a question: Given that many people have understood the causes and consequences of global warming for 30 years, why have we let three decades slide by without decisive response? During this period, accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere and oceans accelerated, and we've had "twenty of the hottest years ever recorded." Meanwhile human beings, and especially those of us in the U.S., have "used more energy and resources in the past thirty-five years than in all of human history that came before." And consider the speed: "Even during the dramatic moments at the end of the Permian Age, when most life went extinct, the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere grew at perhaps one-thirtieth the current pace."

What explains near-total inaction? Inertia was a factor, McKibben shows, and society had other priorities, but he describes how democratic processes that might have responded were hijacked by shrewd distortion of evidence and by demagoguery.

Climate change is a major focus of the first part of Falter. It is an accessible, comprehensive and irrefutable compendium of news from that front, albeit news that may be superseded within months of publication.

McKibben then locates global warming within a matrix of other disruptions. His greatest contribution with this new book is to consider how overreliance on extractive and combustive fossil fuels is connected with the most egregious economic inequality in human history. He links both phenomena to two other areas of unprecedented risk-taking: bio-engineering to redesign and "improve" on nature; and rampant replacement of humans with artificial intelligence and automation.

In all four of these fields, coteries of "barons" (oil and coal magnates, Silicon Valley tech moguls, renegade experimentalists) benefit in the short term, maximizing personal advantage while jeopardizing our shared future.

As a diligent investigator, McKibben names names and follows the money, including a detailed chapter on the Koch brothers' maneuverings. But his exploration of how Americans squandered our 30-year opportunity to address the danger goes beyond data. Our crisis is cultural, and Falter aims a disinfecting light on the antidemocratic scorn shared by many of the leaders of our fastest-growing and most powerful industries, who believe that traditions of civil debate, legislative prudence and judicial circumspection are contemptibly inefficient.

Fast food tycoon and Trump insider Andy Puzder has effusive praise for robots, for example: They're "always polite, they always upsell, they never take a vacation, they never show up late, there's never a slip-and-fall or an age, sex, or race discrimination case."

Bizarre drug regimes and cryogenic preservation of brain matter for eventual uploading to the cyber cloud are symptoms of many of these tech-industry elitists' determination to elude or transcend human limitations. Ray Kurzweil, Google's director of engineering, told McKibben that he takes "about a hundred pills a day"; he has no intention of dying. Likewise, many of the tech entrepreneurs are now investing in space technologies, imagining an eventual abandonment of Earth for pristine colonies elsewhere.

A fascinating connection running through these encounters with the fossil-fuel and high-tech elite is the ongoing influence of Ayn Rand (1905–1982). Many readers will be astonished to learn of the breadth of her cultlike sway; her novels are still revered by such influential devotees as Alan Greenspan, Paul Ryan, Rex Tillerson, Mike Pompeo, Clarence Thomas and the present resident of the White House. According to McKibben, the core of Rand's gospel is, "Government is bad. Selfishness is good. Watch out for yourself. Solidarity is a trap."

While he is an unapologetic partisan — he's cofounder of the activist environmental coalitions Step It Up and 350.org — McKibben isn't a polemicist like Rand. Falter is the work of one of America's most skillful long-form journalists. Like his younger self who traced all of those wires and pipes, McKibben takes on a herculean scope of research and an astounding synthesis of sources, reflected in 20 pages of endnotes.

Yet the voluminous citations never encumber the book's narrative pacing. Page by page, what's most unusual is the natural warmth of his first-person voice: loping in gait, assiduous and methodical but brisk in transitions, probing then reflective.

And there are many exclamation-mark moments. McKibben quotes venture capitalist Tom Perkins, who told New York magazine that in his ideal world, "You pay a million dollars, you get a million votes."

McKibben's previous book was a romp, the feisty satirical novel Radio Free Vermont: A Fable of Resistance. Falter, while more somber and severe, shares with its predecessor an uncannily entertaining way of combining information with interpretation and insight, often embodied in a story. Here is a writer who genuinely enjoys people, who loves spending time with scientists and innovators, and who — though he's thought longer and harder than almost anyone about the danger we're in — finds grounds for measured hope. Somehow he has survived with both knowledge and reverence for life.

The fourth part and the epilogue of Falter are rewards, as McKibben proceeds to examine two examples of what he calls "technologies of maturity and balance": solar energy and nonviolent change. These, he believes, especially if combined, could save humanity and our planet. While one might be tempted just to read the last quarter of the book, its impact is greater in light of the difficult truths that precede it.

"We are messy creatures," McKibben writes near the end, "often selfish, prone to short-sightedness, susceptible to greed ... And yet, most of us, most of the time, are pretty wonderful: funny, kind. Another name for human solidarity is love, and when I think about our world in its present form, that is what overwhelms me. The human love that works to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, the love that comes together in defense of sea turtles and sea ice ... The love that lets each of us see we're not the most important thing on earth, and makes us okay with that. The love that welcomes us, imperfect, into the world and surrounds us when we die."

The original print version of this article was headlined "End Times?"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Books, Bill McKibben, Falter, climate change.

More By This Author

About The Author

Jim Schley

Bio:

Contributing writer Jim Schley has edited nearly 200 books in a wide range of genres and subject areas. He leads book discussions around the state for Vermont Humanities. And as a theater artist, having toured internationally with Bread & Puppet and the Swiss troupe Les Montreurs d’Images, currently he’s performing with Parish Players and BarnArts. He lives in Strafford.

Contributing writer Jim Schley has edited nearly 200 books in a wide range of genres and subject areas. He leads book discussions around the state for Vermont Humanities. And as a theater artist, having toured internationally with Bread & Puppet and the Swiss troupe Les Montreurs d’Images, currently he’s performing with Parish Players and BarnArts. He lives in Strafford.

Speaking of...

-

The Over-60 Crowd Steps Up With Bill McKibben's Climate Action Group Third Act

Mar 29, 2023 -

In His New Book of Drone Photography, Caleb Kenna Rediscovers Vermont From Above

Nov 23, 2022 -

From the Publisher: Special Delivery

Sep 21, 2022 -

Book Review: 'The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened,' Bill McKibben

Jul 27, 2022 -

The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, October 13 to 19

Oct 11, 2021 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. Ever Since the Solar Eclipse, I’ve Been Feeling Weird Ask the Rev.

- 3. Animal Communicator Amy Wild Wants a Word With Your Pet Animals

- 4. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, April 24-30 Magnificent 7

- 5. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 6. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 7. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse