click to enlarge

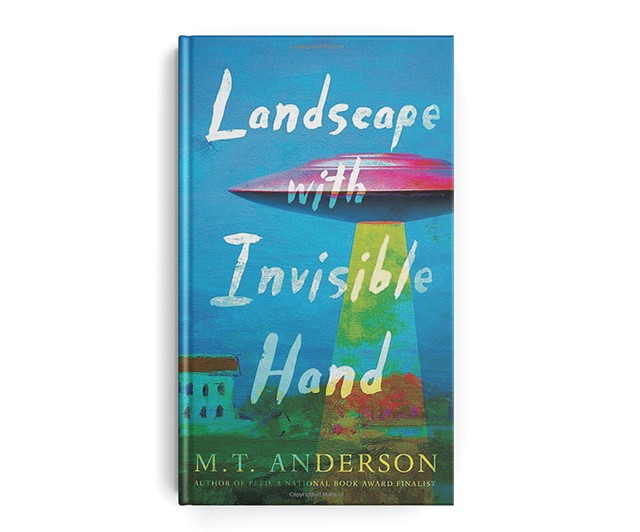

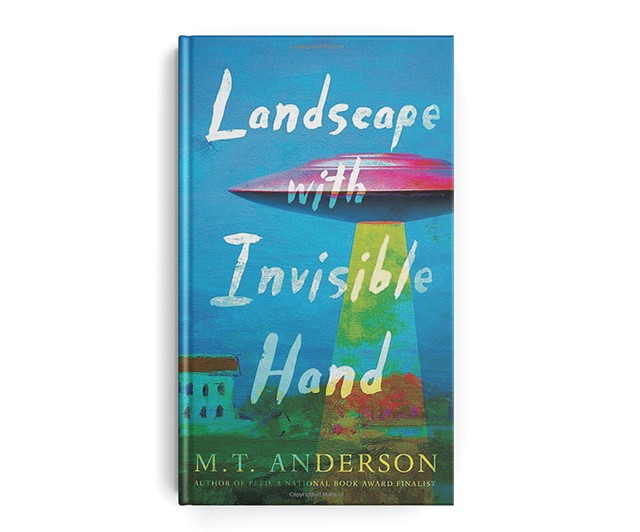

- Landscape With Invisible Hand by M.T. Anderson, Candlewick Press, 160 pages. $16.99.

How do you write a book about the human costs of laissez-faire capitalism that won't make readers' eyes glaze over? Make it about an alien invasion. At least, that's the sly solution that East Calais author M.T. Anderson deploys in his latest young-adult novel, Landscape With Invisible Hand.

The book's 18-year-old narrator, Adam Costello, is an artist. He shares his first name with Adam Smith, the 18th-century father of neoclassical economics. Smith used the metaphor of an "invisible hand" to convey the notion that market forces inexorably work to transform individual selfishness into social benefit.

Although Adam's mom evokes Smith's principle at one point, Adam himself is no economist. He's busy painting and drawing the world around him — a world transformed by the arrival of an alien race called the vuvv.

Technically, these advanced creatures — who look "like granite coffee tables" — haven't invaded at all. They've simply invited Earth to sell its raw materials to them and join their Interspecies Co-Prosperity Alliance. For a few Earthlings, the influx of alien tech has created unimaginable wealth. Most others, like Adam's middle-class family, have seen their livelihoods vanish along with terrestrial industry. Adam tells us, "We watched a billion people around the globe lose their jobs in just a year or two."

In this satirical fable, barely longer than a novella, Anderson imagines Americans learning how it feels to be colonized, economically and culturally, by a race of beings that casually assumes its own superiority to Homo sapiens.

The vuvv take a patronizing, reductive interest in human culture: To them, all our music is 1950s doo-wop, and statues of a crucified Buddha are prized souvenirs of our planet. ("You people are so much more spiritual than we are," a vuvv enthuses.) To keep their families alive, humans learn to cater to these mangled alien understandings. Adam and his girlfriend, Chloe, make money by performing "1950s love" on a video channel for an enthralled vuvv audience (see excerpt above).

Too bad that, after a few months of exchanging endearments such as "Golly, you're marvelous!" and "Gee willikers, the moments we spent apart were torture," the two young people realize they hate each other. "Human love is forever," a vuvv sternly informs them, before demanding restitution for the subscribers they've "defrauded." "It lasts until the end of time."

Local classical music lovers may know Anderson as the author of an acclaimed book on Dmitri Shostakovich and as the force behind text-and-music events such as the Craftsbury Chamber Players' concert of works by experimental Soviet-era composers in May. In the world of teen readers and educators, however, the National Book Award winner is perhaps best known for Feed (2002), a dystopian novel that presaged the rise of smartphones and social media.

In Landscape, Anderson returns to the register of that earlier novel. With a comedian's deftness, he uses a wise-ass teenage narrator to transform potentially ponderous social critique into a compelling story. Fans of George Saunders' CivilWarLand in Bad Decline will recognize a similar alchemy here: Both authors know how to use a strong voice to infuse their social satire with genuine feeling.

Landscape is rich in absurdist comedy, much of it delivered via Anderson's cutting one-liners. When Adam and Chloe attempt to kiss, their mouths are "stuck together uncomfortably like fried onion rings"; a doo-wop standard translated into vuvv "sounds like someone vacuuming shag carpet." But readers who get on board for a jokey allegory will find themselves growing more emotionally invested in Anderson's characters than they expect.

The novel isn't just a spoof on Smith's faith in beneficent market forces; it's also about the dilemmas of artists under corporate patronage. Each of the short chapters, with a couple of exceptions, is titled after one of Adam's paintings. These range from escapist fantasias ("A Crystal City in a Range of Misty Mountains") to sober depictions of his increasingly ravaged hometown ("The Parking Lot of the Looted Old Stop & Shop").

When Adam enters a vuvv-run student art contest — probably his one shot at a better life — he has to ask himself which version of Earth he wants to present: fantasy or reality. The stakes rise as his family's fortunes decline, along with his health.

Anderson's scenario isn't lacking in pointed topical commentary. While Adam's mom stands in long job lines and perkily extols the entrepreneurial spirit, other displaced workers raid bodegas and blame immigrants for their misfortune. Meanwhile, TV pundits decry human "laziness." Adam muses: "I'm not sure there really even was a middle class anymore — just all of us hoeing for root vegetables next to our cracked above-ground pools."

More than a lament for all these victims of the "invisible hand," Landscape is a disenchanted meditation on the ways in which humans (and, yes, probably vuvv) fool themselves into believing that "winning" is their destiny. Faced with their relegation to galactic third-world status, people like those in Adam's family struggle not just with poverty but with a chronic state of denial. "Hell, we're American," Adam says. "We keep on being surprised that victory isn't ours."

But what if good old effort and stick-to-it-iveness don't result in any winning at all? What if the invisible hand just isn't tipping our way? The logic of coming-of-age fiction dictates that Adam will eventually have an epiphany that makes sense of the cognitive dissonance with which he's been raised. The insight he gains is just as darkly, subversively brilliant as this novel itself.

From Landscape With Invisible Hand

I designed a site with us running hand in hand through some kind of field. It's cartoony, so we're more adorable. If you wait for a minute, it switches to a thing where we're on opposite sides of the space, and we run toward each other with our arms out. Then, as we collide, our bodies turn into a burst of flowers and spray through each other. The flowers drift and spell out "Ad & Chloe." Then you can choose episodes.

"Why are we standing in so much grass?" Chloe asked with her arm around my neck. "Aren't we worried about ticks?"

"Maybe it's wheat," I said. "Wheat's nostalgic. As a crop."

"You have some weird ideas."

"Wheat's super American."

"Do they even grow wheat around here? Where do they grow wheat now?"

I shrugged. "Floating around the sun, mainly."

Each episode was one of our dates. We went to a party where I introduced Chloe to people from my school, or we baked snickerdoodles, or we just hung in a parking lot. Each episode had a little title and a description translated into vuvv. "Ocean Memories: Humans Adam and Chloe are going to the beach now! They are in true love. They have playful splashing. The water is too cold for organism Adam and he squeals like a piggy, says loving Chloe! Humans find the oscillating presence of hundreds of billions of gallons of a chemical that could smother them relaxing. This leads to cuddles in mounds of finely ground particulate detritus. 'I'll always be true!' says Adam!"