Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

UVM Cancels Commencement Speaker Amid Pro-Palestinian Protest

-

Education

Education Bill Would Speed up Secretary Search…

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

- Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News 0

- 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis 0

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

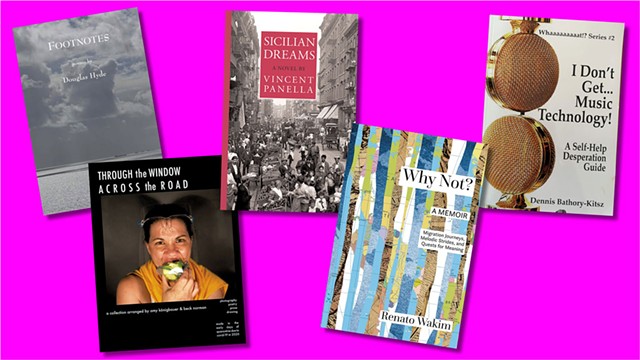

Five Newish Books by Vermont Authors

Published October 7, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 22, 2020 at 11:03 a.m.

Seven Days writers can't possibly read, much less review, all the books that arrive in a steady stream by post, email and, in one memorable case, a committee of raccoons. So this monthly feature is our way of introducing you to a handful of books by Vermont authors. To do that, we contextualize each book just a little and quote a single representative sentence from, yes, page 32.

Inclusion here implies neither approval nor derision on our part, but simply: Here are a bunch of books, arranged alphabetically by authors' names, that Seven Days readers might like to know about.

I Don't Get ... Music Technology!: A Self-Help Desperation Guide

Dennis Bathory-Kitsz, Westleaf Edition, 172 pages. $21.95.

Tape may have left us, but its advances live on.

Anyone who's ever been confounded by byzantine instructions for setting up a new TV or stereo knows how advances in technology can create as many frustrations as they solve. That's especially true in the world of music, where gadgets and gear evolve with the speed of a fast-forward button. To help musicians, engineers and producers keep up, Dennis Bathory-Kitsz recently released the second book in his series of immersive music-related instruction manuals: I Don't Get ... Music Technology!: A Self-Help Desperation Guide.

Bathory-Kitsz is a composer, writer and advocate of contemporary "non-pop" music — a sort of experimental wing of the contemporary classical sphere. After teaching an Introduction to Music Technology course at Northern Vermont University-Johnson, he realized that no book adequately covered the entirety of music production, from creation to presentation, in a comprehensive and accessible way. I Don't Get ... Music Technology! attempts to fill that gap.

In straightforward, conversational language, Bathory-Kitsz covers everything from the history and evolution of recording tech to the latest developments in studio wizardry. Intended for a general audience, the book offers plenty of techie detail to intrigue seasoned engineers while also demystifying the process for home-recording newbs.

— D.B.

Footnotes

Douglas Hyde, Antrim House, 114 pages. $17.

You supply the footnotes.

Douglas Hyde's poetry collection Footnotes is a curious debut, filled with memories of family and meditations on mortality. The title refers to a long poem in dialogue about two people disputing the veracity of their holiday letter-writing tradition. The strongest moments are those that confront the fear of death: In the striking "The Pledge," for example, a woman in a wheelchair keeps up her end of a death pact by smothering her husband with a plastic bag.

Other moments feel awkward. The final poem recounts an anecdote in which a grandfather accidentally appears nude during a video call with his family. Earlier, there's a retelling of an adolescent's first encounter with a naked woman — a stripper at a rural carnival outside Montpelier — that might have been fascinating if not for the prudish way the story is framed. (The "seedy revelations" of the woman's "swiveling breasts" are in danger of corrupting the speaker's "dreams of romance.")

The collection offers lovely lines here and there: "The house shoulders its silence," for example. But surrounding them are descriptions and observations that often feel trivial: hiking with dogs and grandkids, yard chores, vacations, and skiing.

— B.A.

Through the Window Across the Road

Arranged by Amy Königbauer & Beck Norman, self-published, 100 pages. $39.99.

During your hunt for the gods, you may have come upon the realization that the hunt is futile.

It has become a standard not-joke that this year feels impossibly attenuated; life before March seems so very long ago, like a lost childhood. Indeed, the onslaught of 2020 has exhausted our collective amygdalae. And so this selection of photographs, writing and drawings by 23 contributors — created and compiled over five months this year, March through July — feels oddly nostalgic. It also offers something like comfort, measured in relatable responses to the quarantine imposed by COVID-19.

Photographers Amy Königbauer and Beck Norman, who assembled the collection, contribute black-and-white images of individuals and families seen through windows or posed on porches and front yards, some with chickens, dogs or cats. With no explication necessary, the photos convey the remove of "social distance."

The poems, essays and snatches of memoir included here speak to fear, loneliness and isolation but also to resilience, love and gratitude. Some entries, such as Kristina Martzke's "Beloved Seeker," quoted above, suggest existential searching. The blunt exasperation in B. Fox's hand-drawn text says it for all of us: "SUPERCALIFRAGILISTICEXPIALIDOHFUCKALLTHISALREADY."

— P.P.

Sicilian Dreams

Vincent Panella, Bordighera Press, 228 pages. $18.

He closed his eyes and tried to shut out the talk of strikes and revenge and whether they could reach New Orleans.

Social inequities serve as a catalyst in Marlboro author Vincent Panella's historical novel Sicilian Dreams, to be published on November 10.

Set in 1907, the story centers on Santo Regina, a working-class widower in Sicily whose worldview changes after an encounter with real-life mafia boss Vito Cascio Ferro. In the U.S., Regina reconnects with Cascio Ferro — and tangles with another historical figure, New York City organized crime detective Joseph Petrosino.

Panella uses straightforward language sprinkled with Italian terms to spin this fast-moving narrative that acknowledges issues of racial, economic and gender inequality. Supposedly free Black men exist in slave-like conditions, Sicilian workers are cheated out of wages, and women such as Regina's daughter, Mariana, have limited sovereignty over their lives and bodies.

Readers may find themselves transported to another time and place by this story that, in some ways, channels today's pressing issues.

— K.R.

Why Not? Migration Journeys, Melodic Strides, and Quests for Meaning

Renato Wakim, Onion River Press, 428 pages. $19.99.

Part of my pursuit during this period was to not only understand why we do the things we do — and the way we do — but also, what makes the birthplaces where we are brought up to be the way they are.

In July 2018, Renato Wakim's family home in Essex Junction was destroyed by fire. Wakim uses that upheaval to frame his memoir, which chronicles a life of "migration journeys" that eventually brought him to Vermont. "I never felt like an immigrant myself," he writes, "but, rather, one that had the opportunity to choose his own destiny."

Born in Brazil to parents of Lebanese descent, Wakim was drawn during his college years to Berkeley, Calif., where he played his acoustic guitar and washed dishes at the now-defunct Good Earth restaurant. Later, he toured Europe and lived on a kibbutz. After he settled down, the wanderlust remained. So did the "quest for meaning": Wakim peppers his account with quotes from thinkers who influenced him, ranging from psychiatrist Bernard Lievegoed to Albert Einstein to Jethro Tull.

Along with travel, music is a thread through the memoir. "I can't think of a better way to bring people together," Wakim writes — reminding us, as he describes Brazil's tradition of protest songs, that music can be resistance, too.

— M.H.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Books, I Don't Get ... Music Technology, Dennis Bathory-Kitsz, Footnotes, Douglas Hyde, Through the Window Across the Road, Amy Königbauer, Beck Norman, Sicilian Dreams, Vincent Panella, Why Not? Migration Journeys, Melodic Strides, and Quests for Meaning, Renato Wakim

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Margot Harrison

Bio:

Margot Harrison is the Associate Editor at Seven Days; she coordinates literary and film coverage. In 2005, she won the John D. Donoghue award for arts criticism from the Vermont Press Association.

Margot Harrison is the Associate Editor at Seven Days; she coordinates literary and film coverage. In 2005, she won the John D. Donoghue award for arts criticism from the Vermont Press Association.

Pamela Polston

Bio:

Pamela Polston is a cofounder and the Art Editor of Seven Days. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Pamela Polston is a cofounder and the Art Editor of Seven Days. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Kristen Ravin

Bio:

Kristen Ravin was the Seven Days' calendar writer 2015-2021. She also wrote about music and books, and contributed to Seven Days’ parenting magazine Kids VT.

Kristen Ravin was the Seven Days' calendar writer 2015-2021. She also wrote about music and books, and contributed to Seven Days’ parenting magazine Kids VT.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Video: Visiting the Wind Phone at the Lanpher Memorial Library in Hyde Park Stuck in Vermont

- 2. Woodstock Poetry Festival Replaces Bookstock Books

- 3. STRUT! Fashion Show Returns After Four-Year Hiatus Culture

- 4. Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate Poetry

- 5. Shaina Taub's 'Suffs' Earns Six Tony Nominations, Including Best Musical Performing Arts

- 6. Student Film Documents Failed Plan to Cut Books From Vermont State University Libraries Film

- 7. Adam Tendler and the VSO to Premiere Vermont Composer Nico Muhly’s First Piano Concerto Performing Arts

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 5. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 6. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 7. Vermont Poet Sydney Lea on His New Collections of Verse and Prose Books