Published February 10, 2010 at 7:44 a.m.

Living abroad for 40 years will change a man, even a dyed-in-the-wool, sixth-generation Vermonter.

J. Brooks Buxton began what he calls “my corporate career” in management with CitiBank and concluded as president of Conoco Arabia Inc. and director of Conoco Middle East Ltd. Over those four decades he lived in Beirut, London, Riyadh, Tripoli, Tunis and Dubai. Buxton traveled frequently and extensively. He learned Arabic. He educated himself in both the quotidian affairs of the region and its lengthy, storied past. And he amassed a stunning collection of artwork.

Yet, “once a Vermonter, always a Vermonter,” says Buxton’s sister, Carlynn Farr, of Burlington. “With all his travels, Brooks returned home. I think he appreciates it more than we do.”

Perhaps so. When Buxton retired from ConocoPhillips in 2003, he moved back to the town where he started: Jericho. Since then, in an elegant, light-filled home with a valley view, he’s spread out his collection. And he’s established himself as a one-man force to be reckoned with when it comes to preserving material relics and more elusive memories of our state’s rich past.

In Buxton’s home, his foreign acquisitions — among them gorgeous 19th-century albumen photographs from the Middle East, Chinese ceramics and a Paleozoic-era trilobite from what is now Morocco — mingle companionably with American paintings, decorative arts, heirloom furniture and hundreds of art and history books.

But if the mix offers clues to the trajectory of his life, the Vermont landscape paintings and antiques speak to Buxton’s beloved avocation — you could even call it a mission.

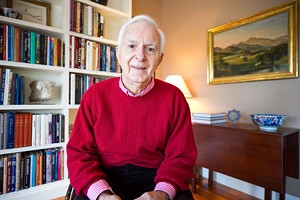

Now 75, Buxton remains an avid collector and, more importantly, a benefactor who regularly gifts Vermont institutions artwork, books, historical documents and other ephemera. A recent example: four town maps by John Johnston, Vermont surveyor general in the early 1800s, given to the University of Vermont’s Special Collections library.

“Brooks has been very generous to us over the years,” says director Jeffrey Marshall, who’s been there for 22 of them. “Many of his collecting interests coincide with ours, so we’re happy when he finds something that he knows is appropriate. We also really value his advice and deep knowledge about books and art in Vermont,” Marshall adds.

Not that all of Buxton’s gifts are Vermontiana. Among the numerous items he has bequeathed to Special Collections are two experimental books created by British earthwork artist Richard Long; one is composed of handmade papers containing mud from rivers around the world. When President Barack Obama received the Nobel Peace Prize last year, Buxton gave the library a signed, limited first edition of President Jimmy Carter’s acceptance speech at his own Nobel ceremony in 2002 — an item he’d picked up at Bauman Rare Books in New York City.

Whatever the donation, “The standard is very high,” notes Buxton, a firm believer in intellectual and aesthetic rigor. “I’m emphatic about that.” While the remark may make him sound elitist, it’s just that he wants the very best for the library and museum at UVM — from which he graduated in 1956 — as well as for the state’s historical repositories. The quality of his gifts, he asserts, “keeps on raising the standards in the state.” Buxton adds, “I hope that years from now students will remember that they saw an important piece at the Fleming or in Special Collections, and they’ll become donors themselves.”

But the possibility of shaping future philanthropists is not Buxton’s sole motivation. He is simply passionate about history. His knowledge is sophisticated and encyclopedic, but his evident delight in sharing it is almost childlike. Even when giving directions to his house, Buxton can’t help including delicious footnotes about the historic buildings, farms and businesses one will pass along the way. He is fiercely protective of the state’s collective memory of itself, and laments the loss of Vermont-made artifacts to out-of-state institutions. Buxton should know; he can rattle off the respective merits of dozens of world museums — from Khartoum to Houston — with the familiarity of one who’s really studied their collections.

You would be shocked, he says disapprovingly, to see the number of pieces of early furniture, items of decorative and folk art, and documents that have “slipped away” — probably from the hands of cash-strapped Vermonters who sold what they could to get by. Buxton seems determined to get back as much as he single-handedly can. And fellow auction-goers ought not to be fooled by the white-haired gentleman in the wheelchair, with his warm brown eyes and gracious manners: Buxton is a tenacious contender.

“After looking at an auction catalog or inventory, he goes in with the organization’s needs in mind,” says Mark Hudson, executive director of the Vermont Historical Society, where Buxton is a trustee. “He has such a tremendous knowledge, you know when he’s donated something it has importance historically to our organization.” And, notes Hudson, while many individuals give artifacts to the VHS, “going to auctions on our behalf is unique.”

It’s part and parcel of Buxton’s style of philanthropy, though. Sometimes a cash contribution is called for. But he’d rather give it specifically for the conservation of objects or paintings or a historic-preservation project, explains Janie Cohen, executive director of the Fleming Museum. The restoration of an 1885 portrait of Frederick Billings for UVM is just one example. Buxton has been on the museum’s board since 2002. But even in the 1990s, when he was either in London or Riyadh, “whenever he came home,” Cohen recalls, “he always wanted a gallery tour.”

“The ways he’s been involved with us are diverse,” Cohen says. “Brooks loves the Fleming building and helped to lead a fundraising effort to restore the Marble Court. He helped us do research when we did the [Lake Champlain] Quadricentennial show. He heads the facilities committee on the board.” Buxton has also donated artworks to the Fleming, including a pair of abstracted landscape paintings by Montréal/New York painter Louise Belcourt and artifacts from the Middle East.

Cohen calls Buxton “very worldly, very cosmopolitan, but very Vermont.”

Buxton may have left ConocoPhillips, but the word “retired” doesn’t describe his level of activity since returning to Vermont. For one thing, he maintains an independent, internationally based consulting business, Buxton Mideast, Inc. that advises on oil- and gas-development projects. “We’re currently working on a major, $12-billion export refinery in Saudi Arabia,” Buxton notes. “There are a lot of economic, legal and management issues in the early stages — particularly legal parameters — to be worked out.”

And then there are his boards. In addition to the Fleming and the VHS, Buxton serves as trustee for the Jericho Historical Society, the Jericho Cemetery Association, the Friends of the State House and — his latest cause — Green Up Vermont. If environmental activism seems like an anomalous interest, Buxton points out rather tartly that Vermonters have always cared for their land. “Why is it that Vermont is the way it is today?” he asks rhetorically, annoyed that anyone would think being “green” is a new concept. “My father would say, ‘Explain to me this organic food … it’s what we all did!’”

Buxton’s love of the land partially accounts for his attraction to early Vermont landscape paintings: “They’re marvelous records of what Vermont looked like” 100 or more years ago, he says. Aside from their obvious attributes — no power lines, highways or big-box stores — the images convey a harmonious, if sometimes hardscrabble, relationship between humans and nature. Paintings in his possession such as James Hope’s “Wedding Cake House” (c. early 1850s) and Sylvester Phelps Hodgdon’s “Hay Fields” (1866) exemplify this pastoral ideal.

“The works in the Buxton collection contribute significantly to our understanding of Vermont as place and idea,” writes artist and publisher Glenn Suokko in Pastoral 10. The latest issue of his Woodstock-based biannual magazine is devoted exclusively to Buxton’s artwork. “I wanted to do a feature on Brooks because he is doing a lot of things for the state,” Suokko says in a phone interview. “His collection is very inspiring.” Suokko first met Buxton at a historic-preservation event that was featured in Pastoral several issues back. The two met up again at the dedication of the Frederick Billings portrait at UVM — the namesake of the former Billings Library, Suokko explains, is the great-great-granduncle of his wife, Ann Billings.

Though the Pastoral feature focuses on Buxton’s historical pieces, his ardor for the past does not keep him stuck in it. His personal collection also includes contemporary pieces by, for example, Wolf Kahn and Claire Van Vliet, and a striking minimalist work on paper by the Belgian artist Jean-Marc Louis. Buxton owns several works by master printmaker Bill Davison and has become pals with the former UVM professor.

Davison recalls the day they met, some five years ago. “Brooks had been on a trip to Montréal with Janie [Cohen] to see an art show, and apparently on the way back he told her he wanted to collect Vermont artists who make prints,” he says. “Shortly after that we arranged a meeting at his house. I took a portfolio and a couple of framed pieces. He bought four for his own collection and one for the Fleming.”

Davison was surprised, “since Brooks’ collection is primarily about landscape.” But, he notes, one of his pieces is “a record of duck hunting on Lake Champlain. Another is about the British Museum — I think that’s what he enjoyed.”

The men bonded, Davison believes, because they’re both native Vermonters — who discovered their parents had known each other. “We had hunted and fished in the same areas of Chittenden County,” he says. “And Brooks also went to UVM.”

Davison remembers with a chuckle leaving Buxton’s house through the garage and seeing some modern masterpieces by such artists as Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Sure, they’re just exhibition posters of the works. But they’re in the garage, framed and neatly arranged on the walls. “I said to myself, ‘I can’t let this guy go from my posse of friends,’” Davison says. “‘He’s too unique.’”

That Buxton is a paraplegic seems almost irrelevant. It’s impossible not to notice that he’s in a wheelchair, of course. Yet Buxton exudes such capability and — there’s no other word for it — indifference to this condition that he puts others at ease about it. He has no truck with anything like pity, and accepts such help as he does need, like an occasional chauffeur, with equanimity. “My lifestyle is different now, being in the chair,” he allows. “But it doesn’t matter; you can still do things.”

Indeed. Buxton has been on a safari in Ethiopia and traveled alone to India, among other international excursions, since a rare nontrauma spinal-cord injury in the early 1990s left him paralyzed from the chest down. But if he brushes off the effects of his disability, he doesn’t mind telling the story of how it happened.

Buxton was simply sitting at his desk in London when two discs ruptured at once. The only warning was some earlier back pain, which a doctor had written off as “normal business-traveling-man bad back,” he recalls. Buxton underwent two significant surgeries, “but the damage had been done.” He spent five months in the hospital and rehabilitation. Typically, rather than dwelling on his own twist of fate, he mentored the other patients. “Spinal-cord injuries are most common in young, active men,” Buxton explains. “A number of them were soldiers or in the police force.”

He soon learned that these men were generally dismissed from their jobs, left with few prospects and no safety net. Buxton also quickly discovered how unaccommodating Britain was to people in wheelchairs. He was spurred to action, and began advocating for the men he met — “Why couldn’t they take a desk job?” he’d demand of employers. He wrote letters. He protested at venues that lacked access. At one theater, Buxton recalls, “I bought tickets and then just sat there, blocking the traffic, until the manager came out and apologized because I couldn’t get in. People would come up and thank me.”

Buxton took his outrage all the way to Parliament, where he became known for his efforts “to improve employment and education,” he says. He also contributed to spinal-cord-injury research in London. “The U.S. and Canada are way out in front on rehab and reintegration,” Buxton declares.

“When Brooks had his surgeries and ended up in a wheelchair, it was very traumatic for all of us,” says his sister. “But it didn’t stop him — he’s been all over.” Farr fondly recollects visiting Buxton in London with her husband and two children. “Brooks took us to the museums, restaurants, everywhere,” she says. “He’s very independent.”

Back home in Vermont, Buxton wheels easily around a tastefully appointed and spotlessly clean house designed by his niece, Lori Buxton Myrick. Her inspiration for the structure, he explains, was the farmhouse in Marshfield where several generations of Buxtons grew up. Though built in 2003, the house has high ceilings and classic architectural details that suggest a much earlier vernacular. And despite the step-free exterior, generous doorways and spacious halls, the house does not shout “handicapped accessible.” Built into a hillside, it has stairs for guests and a discreet elevator for Buxton.

Mostly, though, the house looks like a mini-museum of artworks, books and handsome furniture. There are well-burnished tables, chests, sideboards and chairs, many of them passed down through the family. “My parents and grandparents were aware of good Vermont furniture,” Buxton says. “Mother would always oil it twice a year.”

Family memories loom large at the Old Mill in Jericho, where Buxton’s father was once employed by the E.W. Bailey Grain Co. A vintage photo of the place now hangs in his foyer. Buxton grew up in the house next to the mill, along with his older brothers, Freeman and Ronnie, and his little sister, Carlynn. Buxton likes to talk about outdoor explorations in the area — long before Joe’s Snack Bar became a seasonal institution nearby — and skating on the pond in the winter. Carlynn says her “very bright” brother was fascinated by history even then.

On a recent cold night, though, he’s focused on another kind of story. As program chair for the Jericho Historical Society, which is housed in the Old Mill, Buxton is playing host to a standing-room-only crowd that has come to hear Mark Breen talk about the “vagaries of winter” past and present. It’s not clear whether the attendees are fans of the “Eye on the Sky” meteorologist, obsessed with weather, or simply eager to hear anything related to their hometown hero, Wilson “Snowflake” Bentley. It doesn’t matter to Buxton, who’s tickled at the big turnout.

Before Breen begins his presentation, armed with slides, charts and a laser pointer, Buxton gives a few introductory remarks. Appropriately, given the venue, they are filled with historical anecdotes. Buxton, who can take multiple detours for such details and remember to come back to the subject at hand, is in his element. And he hasn’t a qualm about publicly chiding Breen for using highways as reference points when forecasting the weather on his Vermont Public Radio show.

If they insist on saying “north or south of Route 4,” he worries aloud, will Vermonters forget the place names of their own geography? Is “Eye on the Sky” a GPS service or a weather service? The indulgent smile on Breen’s face suggests he’s heard the admonishment before.

Buxton tells the audience that Breen has driven two hours from St. Johnsbury, a town whose name inspires him to another volley of Vermont history. Its Fairbanks Scales (now the Fairbanks Museum) was one of the state’s first global companies, he reports.

Like all great collectors, perhaps, Buxton shows us the truth of William Faulkner’s dictum: “The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.” “If only Mr. Fairbanks were still around,” Buxton tells his audience almost wistfully, “he surely would have loaned Mark his private train coach for the trip.”

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Q&A: Catching Up With the Champlain Valley Quilt Guild

Apr 10, 2024 -

Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show

Apr 4, 2024 -

Q&A: Meet a Family in Waterbury That Embraces Halloween Year-Round

Feb 14, 2024 -

Video: Goth Family in Waterbury: Sarah, Jay and Zarek Vogelsang-Card

Feb 8, 2024 -

Q&A: Art Entrepreneurs Tessa and Torrey Valyou Celebrate 15 Years of New Duds

Oct 11, 2023 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.