click to enlarge

- Photos Rachel Elizabeith Jones

As the Atlantic announced earlier this year, "The Internet Is Enabling a New Kind of Poorly Paid Hell." The bleak story detailed Americans' increasing reliance on income earned by performing tasks on digital gig platforms. Among the offending companies is Amazon's Mechanical Turk, where workers earned an average hourly wage of $2 in 2017, according to Wired.

Impersonal, geographically diffuse and unregulated, Mechanical Turk's 21st-century "workplace" has drawn in not only hundreds of thousands of work seekers, but also a host of pesky instigators: artists. Among the latter are xtine burrough and Sabrina Starnaman, University of Texas at Dallas professors whose collaborative installation "The Laboring Self," at Castleton University's Christine Price Gallery, critiques the assumption that new forms of digital labor represent progress.

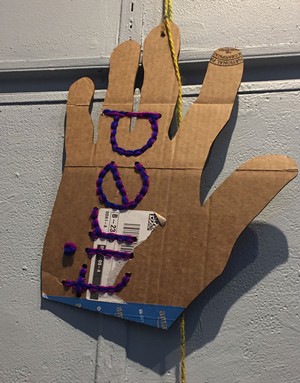

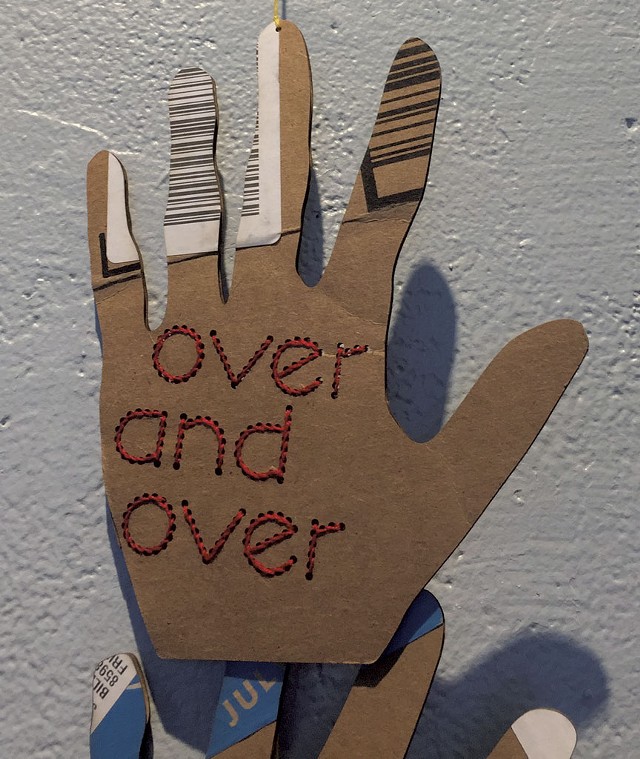

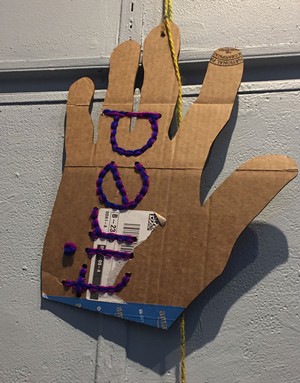

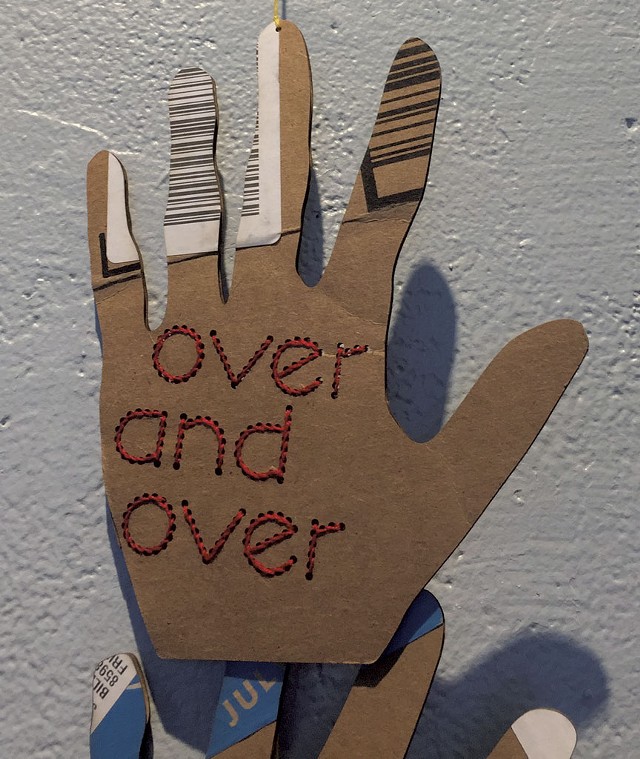

Predominantly a conglomeration of cardboard and string, the exhibition doesn't look like much. Behind the works, however, is a powerful mission: to make visible the labor of "hired hands" in the digital space, and to detail that labor's impact on the bodies and minds of those who perform it. Called "Human Intelligence Tasks," or HITs, jobs available to "Turkers" include taking surveys, transcribing, analyzing data and countless other actions that require a human brain.

"Turking on my couch / destroys my posture," reads a phrase stitched into a pair of cardboard hands, laser-cut from Amazon shipping boxes. Collectively titled "Hired Hands," long strands of eight or so such cutouts cluster in two places in the gallery. Burrough and Starnaman hired workers on Mechanical Turk to trace and measure their hands and asked them to respond to questions about how Turking affects their bodies.

click to enlarge

"In solidarity with our hirees," reads exhibition text, "we embroidered each hand with phrases pulled from their written responses." "MTURK makes my hands sore," reads one. "Makes my eyes tired," says another. One hand just says, "over and over."

Gallery visitors are encouraged to reflect on their own experiences of work at a table strewn with markers and blank cardboard hands. One of the results, distinguishable for being handwritten and not stitched, offers, "It makes me loose [sic] faith but sometimes not."

Starnaman and burrough first met in 2016, long after burrough had become entranced by the possibilities and pitfalls of Amazon Mechanical Turk. She first encountered the platform in 2008, three years after its launch in 2005. That same year, burrough began the now-biennial "Mechanical Olympics," hiring Turkers to interpret various Olympic sports on video for above-average MT wages.

The professors' shared artist statement explains that, after meeting at UT Dallas, they quickly bonded over their mutual "passion for embodiment, literature and labor." Starnaman is a literary scholar with a focus on Progressive Era social reform, and "The Laboring Self" distinctly displays her influence.

A monitor in the gallery provides exhibition background and context, including the origins of the term "mechanical Turk." It also articulates one of the show's central theses: "The work of the contemporary digital worker in the virtual factory is as invisible as the work and body of the factory worker in the 1800s ... As American Literary Realism (1865-1914) brought the factory worker to the public consciousness in fiction, this exhibition brings the digital worker to public awareness."

Burrough and Starnaman make this historical parallel explicit in several ways. "Invisible Labor #1" presents a framed Amazon box with hand silhouettes cut out of it. Mounted on the wall surrounding this work are laser-cut wooden hands bearing phrases from writings on 19th-century industry and industrial workers.

"Working people do not have 'the luxury of grief,'" says one, borrowed from early-20th-century Pittsburgh social reformer Crystal Eastman. "Still more fatal is the crime of turning the producer into a mere particle of a machine," says another, quoting Emma Goldman's 1911 pamphlet "Anarchism: What It Really Stands For."

click to enlarge

Visitors get the opportunity to etch these sentiments into their minds, and onto paper, in a second interactive component. Wooden discs with laser-cut renditions of the quotes share a table with paper and crayons that visitors can use to make rubbings to keep or contribute to the exhibition.

As questions and concerns mount about developments in artificial intelligence, burrough, Starnaman and their anonymous collaborators make a valiant effort to take Amazon's "artificial artificial intelligence" to, um, task. Combining digital savvy and low-fi craft, "The Laboring Self" argues against the internet as an inherently liberating force. It counters that vision by highlighting how bodies and capital are caught in a complex, sometimes overwhelming, web — whether or not we can see it.