click to enlarge

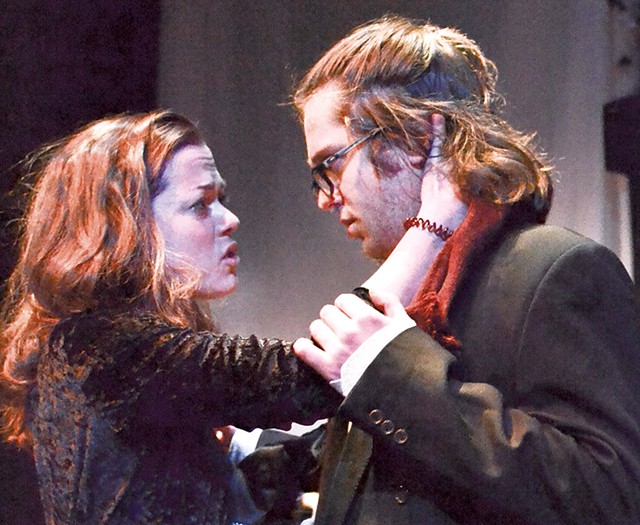

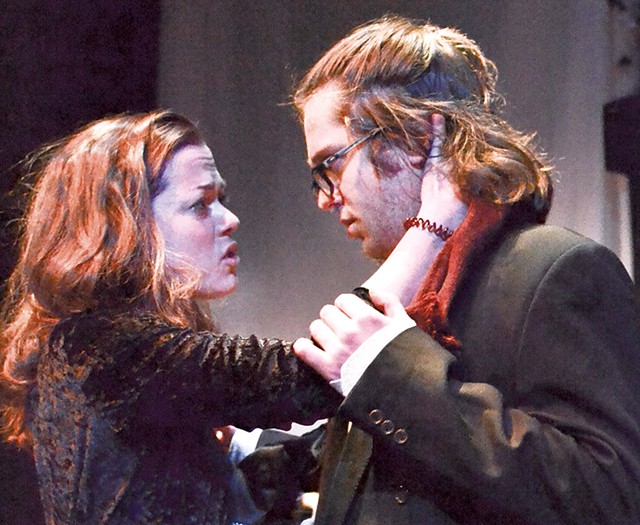

- Courtesy Of Linda Treash/barnarts

- Katie Cawley and Christian Coffman

In Anton Chekhov's The Seagull, everyone is busy pursuing art, love and happiness, and then realizing that, for the most part, all three are out of reach. It's a sad story about comical characters who don't, or at least shouldn't, take themselves too seriously. In the BarnArts production at the Grange Theatre in South Pomfret, a cast of community actors revives a classic play.

First performed in 1896, The Seagull broke away from the melodramatic acting style of the day to usher in psychological realism and nuanced performances. It's hard now to imagine the sharp shift the play represented, but if it can't startle any longer, it can at least feel comfortably contemporary.

Unfortunately, most theaters staging Chekhov today can't resist allowing the period details to make it creak like a relic. This production uses modern dress and changes snuff to cigarettes, but horses, Hamlet references and rigid Russian social classes remain, anchoring the play in a different era.

That's not a problem in itself, but director Aaron M. Hodge substitutes stiff formality for Chekhov's casual treatment of everyday life. The tone is never breezy, and the light comedy is often lost.

Paul Schmidt's 1997 translation strips away the archaic, stilted language, and his text should give performers the calm assurance of matter-of-fact dialogue. But Hodge and the actors work against it, seeking a higher pitch of dramatic speech, probably because the story is actually melodramatic indeed.

It's a play of small, daily details, but the plot includes a shocking and ruinous love affair and a suicide attempt. The biggest events occur offstage, so Chekhov always shows characters reconciling themselves to upheaval, rather than the cataclysm itself.

The story begins with a play. Arkadina (Rebecca Bailey), a famous actress, is visiting the country estate of her perpetually ailing but never really ill brother, Sórin (Daniel Deneen). Arkadina's son, Treplev (Christian Coffman), has written an abstract play in the new Symbolist style that he hopes will prove him his mother's artistic equal. The mother and son are in a battle of wills that neither admits to and Treplev can't possibly win.

The performance is outdoors, beside a lake at moonrise. Treplev is in love with Nína (Katie Cawley), a young woman who lives across the lake. She'll perform the play and hopes to become an actress, an ambition that might be advanced by Arkadina's current lover, the popular author Trigórin (Mark Alloway), who will be in attendance.

Chekhov populates The Seagull with characters high and low, mingling them so we can see how all of them yearn for something they can't quite have. The estate's tedious, self-important manager Shamráyev (Joseph Ronan) wants his version of grandeur, despite being lower class. His daughter, Másha (Chelsea Mojallali), is in love with Treplev and acutely aware of the hopelessness of her infatuation. She decides to throttle her impossible love by marrying a man she cares nothing about, the poor schoolteacher Medvedénko (Cedar Davidson), a man who wants so little yet still can't quite earn that extra kopek.

Shamráyev's wife, Paulína (Courtney Hollingsworth), flirts with Dorn (Jim Schley), the country doctor. She thinks it's her turn for romance, but he has spent his long bachelor life in shallow, brief affairs and feels no need for another. Sórin has always wished to marry and live in the city; he finds himself near the end of his days alone in the country. Trigórin would rather go fishing than bask in his fame.

A set of characters ineffectually exploring their chronic dissatisfaction offers a director several choices. As written, these people can elicit compassion or contempt, so directors are free to explore anything from cynical humor to deep psychological dredging to taking a stab at pure pathos. In this production, Hodge focuses on the romantic doom of Nína and Treplev, parking the other characters mostly in the shadows. Nína's downfall is getting what she thinks she wants; Treplev's is neither getting Nína nor the artistic success that could make up for losing her.

Hodge emphasizes the dramatic arc for these two characters, but because their darkest events occur offstage, he doesn't have the action to make them sensational or the words to make them woeful. Chekhov withheld those elements to show a different kind of dramatic reckoning, but in this production the performers portray the suffering through somewhat superficial acting. We see an actor raise an eyebrow, but we don't see a character feel the little shock that makes it impossible not to raise an eyebrow. It's acting from the outside in, and even though it may be heartfelt, it can read as mannered.

All the performers have nice moments and show what's at stake for their characters. Chekhov counted on an ensemble to tell his story, and The Seagull is built on contrasts between old and young, jealous and confident, despairing and hopeful that these disparate characters embody. To make it work as theater, the acting ensemble has to engage with each other and create a whole larger than the sum of its parts. As the run continues, these performers may start to connect more fully, but on opening night the show was still a collection of individual efforts.

If Shakespeare pushes actors to emote to the breaking point, Chekhov humbles them with language so plain that a pause and a glance will do all the work. The secret is trusting it, because the story itself beckons actors to overdo the humor or the despair, or both.

This production seems to be searching for something grand in Treplev's artistic quest and Nína's downfall, but the text doesn't cap events with tidy morals. The company has located the tragedy for the characters but not quite found the comedy that surrounds it.