Published November 21, 2007 at 12:47 p.m.

We've all heard the Thanksgiving story where the cook forgets to stick her hand in the turkey's body cavity and extract the bag of squishy organs. Sure, it's kinda gross in there — but anyone who's omitted that step knows the tale ends with someone fanning smoke away from a blaring alarm and running to the store for a back-up bird. Good luck finding one.

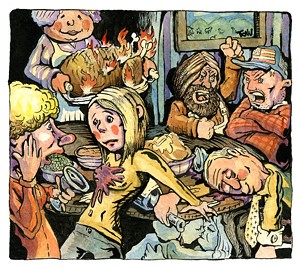

Few people's holidays end with the arrival of the fire department or a trip to the ER. But that doesn't mean putting an elaborate meal for 20 — or 10, or two — on the dinner table is a breeze, especially when familial tensions, hours of food prep and altogether too many cooks come into play. Though real disasters are few and far between, little things seem to go awry on a regular basis.

Yep, we're counting the rude comments Aunt Ethel makes when she's downed too many glasses of sherry, and the experience of watching your fave football team go down in flames — even when your stuffing doesn't.

Seven Days asked a few Vermonters to share their Thanksgiving travails for your reading pleasure.

Matt Birong, 3 Squares, Vergennes

Why settle for a plain old turkey when you could partake of a Cajun dish called turducken? Local lore, perhaps apocryphal, tells us this is an American twist on a classic Bedouin wedding dish. The original supposedly involved a camel, a sheep, several chickens and some fish. (Or was that a dirty joke I once heard?) In the States, a turducken is a turkey stuffed with a duck stuffed with a chicken. For good measure, enthusiastic chefs sometimes fill the chicken with sausage. In other words, it's cardiac arrest on a platter.

And it's just the kind of challenge that Birong, a culinary school grad and chef-owner of 3 Squares in Vergennes, likes to tackle. But the first time he made one, things didn't turn out quite as expected.

With 12 hungry people waiting at the table, Birong removed the concoction from the oven, let it rest so the copious juices could redistribute, and made an incision. "It was raw in the middle," he recalls. "I wouldn't say sashimi, but it was close." He'd been fooled because "it was such a mass of poultry that the thermometer didn't penetrate to the middle of the bird," he guesses.

Birong butterflied the meat and threw it under the broiler. In the end, the turducken was served and enjoyed. But for the sports fans in the room, all was not well. "We ended up eating an hour and a half late," Birong says. "It interrupted the football games a little."

Susan Reid,King Arthur Flour, Norwich

King Arthur Flour knows all about the potential for kitchen disasters — the company runs a baking emergency hotline. When a question stumps the folks at the phones, they refer it to Susan Reid, a former NECI chef-instructor and Culinary Institute of America graduate, who helps write King Arthur's cookbooks and bi-monthly newsletter.

Reid has heard her share of holiday sob stories. In fact, explaining how she handles sticky pastry questions, she sounds more like a therapist than a gastronome. "We're talking to people in the middle of crises," she explains. "A lot of times they want to make a substitution but are afraid to. We validate them and give lots of permission."

But some deviations from the instructions are, well, problematic. "One person put a full cup of yeast into a recipe, and it was crawling out of her oven," Reid relates. Another "called in high dudgeon to tell us our key lime pie recipe was awful." Unable to find three bottles of key lime juice, the customer had instead used lime oil, typically dispensed by the drop.

Though she's managed to avoid such faux pas, Reid has her share of grueling Thanksgiving memories: She used to work lengthy Turkey Day stints at the Bedford Village Inn in Bedford, New Hampshire. "It was the same meal, served over and over again for 10 hours," she says. "It was family style. We probably did 70 or 80 turkeys. We had a 120-gallon steam kettle in the corner, and it was filled with gravy," she remembers. "There were turkeys everywhere . . . it was brutal."

Gary and Patty Sundberg, Island Ice Cream, Grand Isle

"Patty and I have been pretty lucky," Gary Sundberg relates, "We've never had a bad Thanksgiving." They do, however, have a cautionary tale for anyone who's hoping to be in the gravy. One year, Gary got a little too aggressive with the lumps. "I wasn't supposed to stir as hard as I did," he admits. "I stirred the Teflon coating right off of the pan . . . Then I asked, 'What's all this black stuff in the gravy?'"

The mistake sent the Sundbergs running to the grocery store for packets of gravy powder, chock-full of yummy ingredients such as autolyzed yeast extract, partially hydrogenated soybean oil and modified potato starch. Sounds just like the homemade stuff, no?

The fate of the cookware was even less savory, Gary explains: "It was one of those big roasting-pan things with the steel handles. Something that Patty really liked. I think it made its way to the trash bin."

Robin Bertrand, Stern Center for Language and Learning, Williston

Without the proper equipment, the simplest kitchen task can turn into a nightmare. Especially when guests are a bit tipsy. Another gravy tale with gravitas comes from Robin Bertrand. When they were newlyweds, she and her husband proudly hosted their mothers at their new condo, which lacked a well-stocked kitchen. "We had to use one of those foil roasters for the turkey," Bertrand says.

Not feeling particularly confident in front of the stove, she was relieved when her mother and mother-in-law offered to make the gravy. "The turkey was resting, we'd been drinking wine, and they were stirring and stirring," she says.

After a time, one of the women noticed the pan was looking a little dry. "My mother added more water and flour," explains Bertrand. But a few minutes later, they were still puzzled: The gravy kept disappearing.

Finally, they discovered that their vigorous stirring had poked a hole in the foil pan. "All of the gravy went down through the electric burner into the hole in the oven . . . The entire top of the stove was full before we figured it out," Bertrand chuckles.

The cleanup was no fun and, worse, they had to eat naked mashed potatoes.

Sean Buchanan, Wood Creek Farm, Bridport

The garrulous Buchanan, host of Vermont Public Television's "Feast in the Making," couldn't stop at just one story.

As a youngster, Buchanan enjoyed eating off a set of dishes with pictures of an adorable bunny — until one Thanksgiving, when he was about 10 years old.

"My mother was a really eclectic cook," Buchanan explains. That year, she augmented her Thanksgiving menu by preparing a rabbit. "I remember being horrified," he says. "I had to eat rabbit off my Peter Cottontail china. There was a little bunny on the plate smiling at me." It took Buchanan 15 years to learn to love eating the lepus.

Like Reid, Buchanan also knows what it's like to cook Thanksgiving for an army of resto patrons. Years after his run-in with the painted cottontail, he worked as executive chef at a Colorado resto. "We did a Thanksgiving buffet, and we based the numbers on the year before," he recalls. But the meal proved way too popular: "About halfway through, we were almost out of everything."

Buchanan had to turn to the local mega-mart. "I called the grocery store at 6 o'clock at night, and they had 20 pre-packaged meals they didn't know what to do with," he says. "The first people got the really good, home-cooked Thanksgiving meal." The others . . . well, their turkey and sweet potatoes may have tasted a little canned. Does Buchanan regret the deception perpetrated on the latecomers? "You've gotta have food, that's what it comes down to," he muses.

Rob Litch, Misty Knoll Farms, New Haven

Litch, who raises thousands of turkeys at Misty Knoll, sees a side of Thanksgiving most people never witness — the one that involves feathers, squawking and lots of turkey poop.

Even with nearly 20 years of poultry production under his belt, things on the farm sometimes get, er, fowled up. A few years ago, Litch recalls, "Everybody wanted turkeys in the 16-pound range." But he hadn't started enough birds at the right time, and quickly ran out. "That was my worst sizing year ever," he recalls with a groan. "I was able to offer them 12-pound birds and 20-pound birds . . . I remember a stream of angry people."

Paul "Archie" Archdeacon, Gracie's, Stowe

Though Gracie's recently hosted a "game dinner," Archdeacon, the restaurant's owner, isn't a fan of firearms. So when his brother-in-law, who resides in Springfield, Massachusetts, invited him to a Thanksgiving "turkey shoot," he was quick to decline. "I told him I was afraid of guns and didn't want to go," he says.

His brother-in-law wasn't having it. "He dragged me along," Archdeacon recalls. With a heavy heart, he climbed into the pickup truck and braced himself for an unpleasant morning. At 10 o'clock, they arrived at a friend's house, ostensibly to round up the hunting crew. The men, 20 or 30 strong, gathered in the basement.

But something was wrong. Nobody was in camo — and instead of rifles, the guys bore booze. Their version of a turkey shoot turned out to involve making obnoxious gobbling noises and "shooting" bottles of bourbon — Wild Turkey brand, of course.

Archdeacon may have been relieved, but not everyone was happy. "At noon [the friend's] wife came down and started yelling that we were ruining her Thanksgiving," he relates. Pissing off the missus seems to be a tradition 'round those parts — according to Archdeacon, the yearly "turkey shoot" is approaching its 25th anniversary.

Crystal Maderia, Kismet, Montpelier

When customers read the menu at Kismet, the cheerfully decorated Montpelier restaurant Crystal Maderia owns with Alanna Dorf, they know right away they're in the hands of hard-core localvores. The crunchy café goes through three or four pounds of organic local bacon on weekdays, and more during weekend brunch. Its website lists Green Mountain sources for a host of ingredients, from pastry flour to polenta.

Can you keep it local and still feast on Thanksgiving? A few years ago, Maderia — living at the time in the coastal city of Mendocino, California — gave it a try. At the time, the word "localvore" hadn't yet been coined. "My partner and I decided we'd start a new tradition of only having local foods for our Thanksgiving meal," she says. But after weeks of searching, they weren't making much progress. Perhaps because they'd limited themselves to ingredients from just three towns.

Meat came from an unlikely source. "One person called me randomly in the middle of the night and said that he'd found a deer that had been hit by a car and asked me if I wanted the meat . . . I was psyched. It was a score," Maderia says. "We went out to the woods and left apples as gifts for the deer spirits."

With the main course taken care of, there was still the problem of sides. "I scoured the woods for two days looking for mushrooms," Maderia says. Luckily, she found a couple of big ones, and some wild berries.

Although the vegans who joined the couple for dinner hadn't eaten meat in 10 years, they decided to partake of the venison. "It was all we had," Maderia recalls. "We had huckleberries, mushrooms and road kill."

Laura Kloeti, Michael's on the Hill, Waterbury

Holiday-meal planning is a constant tug-of-war between the cautious — the types who request the same green-bean casserole and mashed sweet potato with crunchy marshmallow topping year in, year out — and the adventurous. But even the latter know each culinary experiment is a gamble. Laura Kloeti found that out about five years ago, when she tried a new method of preparing her family's Thanksgiving turkey. "I smoked a turkey with hickory chips on the BBQ and then basted it with Guinness beer," she describes. Visually speaking, it was a smashing success — "the most beautiful golden-brown turkey ever."

Although it was thoroughly cooked, the poultry "had a pink tinge to it," says Kloeti, as smoked meats often do. And that wasn't the only source of cognitive dissonance. "The whole time, throughout the meal, everyone kept making comments about . . . how it tasted exactly like a ham," Kloeti confesses. The final verdict: "It was delicious, just not a 'Thanksgiving Turkey.'"

Marialisa Calta, food writer, Calais

Holidays may be blatantly commercialized, but they still give us a chance to reflect on what's truly important — if we can find time between mediating the family rows and basting the turkey.

On one such day of thanks, 20 years ago, Marialisa Calta got a bit of a wake-up call. During a blinding snowstorm, she'd gathered with a group of friends at the East Montpelier home of Nona Estrin, an author and artist. The meal was a potluck. Most of the gang was there, but fellow writer Andrew Nemethy — accompanied by the all-important potato dish — was still missing.

Then came a phone call. Nemethy had flipped his car, but wasn't injured. "We were greatly relieved to know that he was unhurt . . . but the unspoken question was, were the potatoes OK?" Calta divulges.

She continues: "A party set out to go and collect Andrew, and took a picture at the scene: Andrew — snow falling all around — standing in front of his upside-down car, holding the pot of potatoes."

Yes, the potatoes survived — and, Calta concludes, "a great Thanksgiving was had by all." Goes to show: Even when the gravy's lumpy or the turkey's raw, or half your guests decamp mid-meal to see that new Stephen King movie, this is a time to remember that the two most important things in life are the people you love and the food they make.

When Thanksgiving Was a Movable Feast

"Franksgiving" - it sounds like a holiday devised by Oscar Mayer, or maybe some unholy Turkey Day corpse reanimated by a mad scientist. In fact, it's a reminder that Thanksgiving as we know it is a pretty recent invention.

In 1621, the Pilgrims didn't wait for the fourth Thursday in November to give thanks. They were thankful enough in October. (Canadians still are.) After all, there were no football rivalries or mega-malls in search of shoppers - nothing to dictate a fixed date.

After the American Revolution, presidents changed the date of Thanksgiving whenever the spirit moved them. They also declared days of fasting - which, oddly enough, have not become national holidays. President Lincoln settled the matter (or so he thought) by proclaiming Thanksgiving to be the last Thursday in November. And there it sat . . . until 1939.

Clearly, Lincoln hadn't done the math. Three hundred-sixty-five days in a year divided by seven days in a week leaves a remainder of one day . . . which means each date falls on a different day of the week each year. Eventually it came to pass that Lincoln's Thanksgiving fell on November 30, leaving only 24 days before Christmas!

Shopping days, that is - and in 1939, as the U.S. struggled out of a severe depression, those days were even more precious than they are today. The business community pressured President Franklin D. Roosevelt to push the date of Thanksgiving back a week, to accommodate more pre-holiday spending.

But in August, when Roosevelt leaked the impending change, all hell broke loose. Football fans feared a fumble - schedules with classic Thanksgiving Day rivalries would have to be reshuffled or accept the lower attendance of a game played in the middle of a work week. Poultry producers protested - the change would mean a week's loss of growth for the birds and warmer weather for shipping. Pundits penned polemics.

In October, FDR issued his proclamation: For the year 1939, Thanksgiving would fall on Thursday, November 23. The decree applied to all federal employees, plus the citizens of Washington, D.C., and the territories. Governors decided for their respective states.

Vermonters were not impressed. Governor George Aiken made his proclamation: "Ain't gonna happen" (or words to that effect). In fact, the governors in traditional New England - Republicans all - thumbed their noses at the Democrat in the White House and stuck with November 30. So did 17 more of the 48 states. Twenty-two switched to "Franksgiving." The remaining three double-dipped.

The Thanksgiving breakdown of the states didn't completely mimic political lines, but one wag remarked: "The Democrats get turkey on the 23rd; the Republicans get the leftovers."

In 1941, Congress put its foot down and made Thanksgiving a national holiday - celebrated, by law, on the fourth Thursday in November. Let us be thankful.

The Seven Days guide to NOT spoiling Thanksgiving

DON'T:

1. Wonder out loud about the number of calories in a splash of gravy or a sliver of maple pumpkin pie. Nobody wants to think about it on a holiday, not even you.

2. Judge each dish as if you were on "Iron Chef." Aunt Betty will probably cry if you remark that the mashed sweet potatoes with marshmallows are "a little one-note," and she "could have been more creative with the presentation."

3. Show up with a bowl of healthy quinoa instead of the buttery mashed potatoes you were asked to bring.

4. Answer in menu-speak when somebody asks what's in the salad. The correct answer is "Greens, walnuts, apple slices and cheddar cheese." Not "organically grown baby mesclun mix from Crazy Creek Farm, hand-harvested English walnuts, sliced Gravenstein apples plucked in a pesticide-free orchard on the shores of a windy lake, and cave-aged cheddar made from raw Guernsey milk." See, you're bored already.

5. Calculate the green-bean casserole's carbon footprint. The "inconvenient truth" is that nobody really wants to know. Not today.

6. Initiate a Bobby Flay-style Thanksgiving throwdown. If you're at Uncle John's, then Uncle John makes the best fixins ever. Period. Even if the stuffing is dry, the gravy is lumpy, and you have a degree from NECI.

7. Announce that "meat is murder" and start handing out PETA pamphlets just as Grandma totters triumphantly from the kitchen with the turkey.

More By This Author

Speaking of Food, culture

-

Q&A: Howard Fisher Delivers Meals on Wheels With a Side of Good Cheer

Dec 20, 2023 -

Video: Howard Fisher Delivers Meals on Wheels

Dec 14, 2023 -

Q&A: Alexis Dexter Rescued 57 Shelter Cats During the July Flood

Sep 13, 2023 -

Video: Two Months After the Flood, Alexis Dexter Rebuilds Kitty Korner Café in Barre and Continues to Rescue Cats

Sep 7, 2023 -

Video: Saying Goodbye to Burlington’s Penny Cluse Café

Nov 17, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.