Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

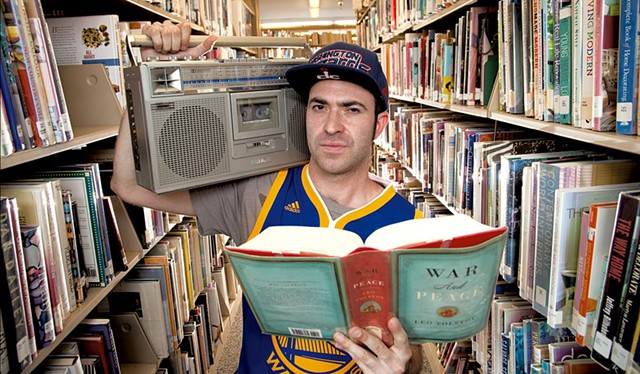

Checking Out Burlington Rapper Learic

Published July 30, 2014 at 11:01 a.m. | Updated October 8, 2020 at 5:25 p.m.

Devon Ewalt, aka Learic, is seated at a table at a bustling Burlington café, his long, sturdy frame leaning casually against his chair. A dog-eared copy of Three Days Before the Shooting..., Ralph Ellison's unfinished second novel, rests beside his coffee mug. He furrows his dark, thick eyebrows, his mouth pursed in concentration. Then a sly grin creeps across his face.

"The first time I ever recorded anything, it was myself rapping 'The Humpty Dance,'" Learic says in his rich, full baritone, referring to Digital Underground's chart-topping 1990 single. "My voice hadn't changed, so it was a pretty funny recording."

Now 33, Learic has grown up a bit since he was a 9-year-old kid laying down on cassette tapes squeaky Shock G tracks about getting busy in Burger King bathrooms. The local rapper's chosen name is actually an acronym for "Learning Entirely About Reality Is Critical." He's a cofounding member of seminal Burlington hip-hop act the Aztext, which remains Vermont's preeminent rap export.

But since that group has gone into semiretirement — or at least has scaled back its previously grueling schedule of performing and recording — Learic has come into his own. He has ascended as a dynamic, provocative and — with apologies to his longtime Aztext cohort, Pro — prolific voice in Vermont music.

This year alone, Learic will star in at least four of the most impressive and artistically bold recordings released in Vermont, in any genre. And that's not hyperbole.

For example, take Unusual Subjects, his recent album with young rap protégé Kin. The record is easily the rawest of the 2014 efforts to which Learic has lent his name — perhaps even his rawest since the Aztext's 2006 debut, Haven't You Heard? But it still ranks among the better recent local hip-hop recordings in an increasingly crowded and talented field. It's a field Learic has helped groom and grow.

Then there is This Is How It Must Be, Learic's collaboration with local songwriter and producer Jer Coons and Eric B. Maier as the Precepts. Built on catchy, collectively written pop hooks and given life by eclectic beats and live instrumentation, it's unlike any local hip-hop record ever made. But Learic has long made a habit of doing things a little differently from anyone else.

For example, the Aztext ran well ahead of the industry curve by releasing their 2011 album, Who Cares If We're Dope?, as a serial record in four shorter "episodes," each helmed by a different producer. It was an ingenious move that helped the band stay relevant after a long hiatus and reminded audiences from Vermont to Europe that the Aztext were, are and always will be dope. Perhaps not surprisingly, one of Learic's 2014 releases will be a new Aztext joint.

But before that album hits, fans will consume Take Flight, Learic's forthcoming EP with producer Dante Davinci — aka JJ Vezina of Upsetta Records — as the Write Brothers. Cinematic in scope, the project was written less as a collection of traditional rap songs than as a series of thoughtfully considered narrative vignettes. The EP has already caused a stir among hip-hop bloggers across the country, thanks to its high-flying first single, "Extraordinary I." Those in the know locally, such as rapper and Vermont Hip Hop News blog founder Justin Boland — aka Wombaticus Rex — have good reason to believe Take Flight will be the next Vermont hip-hop record to garner serious national attention.

"If it doesn't blow Devon's shit up," says Boland of the Write Brothers record recently over beers at the Daily Planet, "then something is just really wrong with music."

Learic has been regarded as one of Vermont's most technically gifted and cerebral rappers since the Aztext's mid-2000s heyday — and likely even earlier, with his band the Elementrix and as a frequent collaborator with influential hip-hop group the Loyalists. He's also virtually peerless as a freestyler and widely acknowledged as the state's premier battle rapper. Now the strength and scope of his latest output attest that he's reaching unprecedented artistic heights. Learic is not merely upping his own game, he's changing the game for everyone else in Vermont.

Listen to any Learic track, and a couple of things will become immediately clear. One, while he raps with an identifiable style and swagger, he's versatile. Just as importantly, he's adaptable. For example, with the Aztext, Learic's flow is often more purposeful and measured than that of his partner, Pro, who's typically the more acrobatic linguist of the two. That's less a reflection of Learic's ability to deliver tongue-twisting bars than of his understanding of how he can best play to his partner's strengths.

Though he's well equipped for a starring role, Learic is perfectly comfortable cast as the straight man — no doubt owing to his time spent studying acting at the American Musical and Dramatic Academy in New York City. But dig on this flashy line from "Extraordinary I," and it's obvious he's easily capable of nimble wordplay:

Life's passing me by like a marching band.

Ask Gary Larson if he's a Pharcyde fan.

Animated, illustrated, canister-contaminated,

causing animals to mutate and move up the food chain.

The second thing about Learic that bears notice is the wealth and variance of cultural reference points embedded in his rhymes. You'll rarely hear him get lazy and rap about how good a rapper he is. Instead, he challenges listeners — and other rappers — to keep up by incorporating clever nods to hip-hop, film and classic literature, among his myriad interests.

For example, after that "The Far Side"/ Pharcyde/Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles line, he goes on to spit about research chemists, American history and the video-game characters Mario and Luigi.

"How many rappers do you know that can reference Kool Moe Dee and Keats, not just in the same song but the same sentence?" observes Pro, whose given name is Brian McVey, in a recent phone interview.

Answer: maybe just one.

Learic is a cultural sponge. He's a voracious reader who carves out time daily with books the way some people block out time for yoga or running or breakfast. He's a font of knowledge about film, both highbrow and lowbrow, and he can talk pretty much any style of music for hours on end.

Learic was born in the Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., the second child of a George Washington University English professor (mother) and a land-use lawyer who also logged time as a teacher (father). He says he was introduced to the classics at an early age, which helps explain his insatiable intellectual appetite.

"They surrounded me with literature," Learic says of his parents. But he adds that his immersion in the works of Shakespeare and Keats was hardly oppressive. "The approach was never daunting. They didn't force it on me," he says. "It was just, like, 'Look at this.' That doesn't mean I didn't watch Saturday-morning cartoons and movies. Literature was just always part of it."

So was music. Learic says his entire family loved music, if with divergent tastes. His mother adored folky singer-songwriters such as Joni Mitchell and James Taylor. His father was into blues. His older brother was a jazz aficionado, always putting Miles Davis and John Coltrane on the stereo.

"I learned to absorb everything," says Learic. "It was never compartmentalized."

He credits his childhood in D.C. with fostering his love for rap music.

"The way I rap and the people I've modeled myself after was shaped by the place I grew up," he says. He bought his first rap tape, Naughty by Nature's self-titled debut, when he was 10 years old.

Northwest D.C. is hardly the ghetto; it's one of the city's better areas. But it is an urban neighborhood whose cultural demographics make Vermont's pale in comparison. Learic, who is white, says he was often in the racial minority in school. He points this out not to bolster some phony notion of street cred but to illustrate that hip-hop was ingrained in him in much the same way the Bard and Satchmo were.

"Hip-hop was part of the culture," he says simply.

It was not, however, part of the culture in Hinesburg, Vt., the rural community where his family moved when Learic was 11.

"I was a city kid," he says. "To me it was a one-horse town. There was, like, one of everything. I didn't know if I could do it."

Learic's sense of culture shock receded somewhat when his family moved to Essex Junction, a town that has perhaps two of everything but was physically closer to Vermont's version of an urban environment: Burlington.

"It was not an easy transition as a lover of hip-hop," Learic says of the relocation to Vermont. "Socially, it was hard."

This was the early 1990s, when alt-rock and grunge ruled the airwaves — just before Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg would make rap more palatable for suburban audiences with 1992's The Chronic.

"I loved Nirvana and the Offspring, too, and still love Weezer," Learic says. "But I loved hip-hop."

He eventually found a kindred spirit in middle school named Daniel Gillian.

"He had the baggy hoodie and jeans, so I knew we were probably into the same stuff," says Learic.

The two bonded over their intellectual curiosity as well as a shared love of hip-hop. Still in middle school, they read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Then, taking a page out of that book, they began reading the dictionary.

"People would think we were so weird for reading the dictionary," recalls Learic. "And we were like, 'Well, Malcolm X did it.'"

Learic's first rap, if it could be called that, was a poem he wrote in sixth grade in response to Rodney King's beating by LA police. He can still recite the first four lines from memory:

Rodney King was a helpless man

LAPD was like the Ku Klux Klan

They beat him and they beat him and they wouldn't stop

It's hard to believe he was beat by a cop.

"Yeah, it was poetry," Learic says. "But it made that jump into the timing and cadence of rapping."

Learic began messing around with his parent's Yamaha Clavinova, a digital piano, and recording rudimentary beats. He also started writing more raps, which he describes as containing mostly earnest, bumper-sticker-level wisdom. Or exactly what you might expect from a 14-year-old kid.

"It was really well-intentioned; it just wasn't very good," Learic says. "I was trying to sound like a rapper."

He crafted a four-song EP, intended only for the ears of some best buds. One night, he played the tape for a friend in the parking lot at a Vermont Expos game. The following Monday at school, other kids were talking excitedly about it. Young Devon Ewalt discovered his friend had played it during a study hall.

"That was the moment I believed I could do it," Learic says.

Soon after, he started his first rap group with fellow Essex High schooler Jeremy Donahue; they called themselves Learic and Phantom. In their senior year, the duo released an EP under the new name Subliminal Messages. Donahue eventually changed his rap name to Framework, and later cofounded the Loyalists. Learic credits that group, which preceded the Aztext, with laying the foundation for the current generation of Vermont hip-hop.

After high school, Learic reconnected with his childhood friend Dan Gillian. Together they founded the live hip-hop outfit Elementrix. That Burlington group also included Dan Schwartz, who now plays in the Philadelphia indie-folk band Good Old War. Elementrix achieved a modest degree of success, including touring New England and opening for Spearhead.

During that show, Learic freestyled onstage with Spearhead MC Radioactive. If his first mixtape was the catalyst for taking rapping seriously, holding his own with Radioactive was the moment Learic understood he could make it his life.

"When you're a local musician, you wonder, Am I good for here, or am I just good?" he says. "But there are moments in your life when you realize you are that good. That was one of them."

Learic no doubt experienced many such validating moments as a member of the Aztext. For about five years in the mid-2000s, they were not only Vermont's highest-profile rap group but one of the state's best-known and most respected musical acts, period. The Aztext had fans all over the United States and Europe.

But eventually the grind of touring and making records began to wear, particularly on McVey. The rapper started to question how much energy he could devote to music now that he had a family and a demanding job as sales manager at Dealer.com.

So the duo put the Aztext on the back burner. Learic, still hungry for making music, began performing Aztext material solo — with McVey's blessing.

"There was never animosity about that," says McVey, who has known Learic since high school. "We both knew I couldn't keep up with it anymore. And it's been really gratifying to watch him do his thing."

A world of new collaboration opportunities soon opened up. Learic began regularly guest rapping with the Lynguistic Civilians, the current face of Vermont hip-hop and a band heavily influenced and inspired by the Aztext.

"It's safe to say that, without the Aztext, there might not be a Lynguistic Civilians," says the Civilians' MC Scott Lavalla, aka Vermonty Burns. "Seeing their live show when I was a teenager growing up in Hartford, Vermont, buying their albums and seeing that they have songs with guys like [New York rappers] Double A.B. and Wordsworth, that was an eye-opener."

Blogger Boland, a Northeast Kingdom native, had a similar experience, though his reaction to the Aztext was slightly different.

"We all kind of hated them," he says with a chuckle. "But it was just jealousy because they were so good. When I got to know Devon, I realized he was all about Vermont hip-hop and doing whatever he could to help the scene grow."

Boland adds that Learic is "one of, if not the, best freestyle rappers I've ever seen, anywhere."

In addition to seeking out opportunities with other producers and rappers, Learic began devoting his energy to rap battles — freestyle rap competitions in which the goal is not only to rap better than your opponent but to mentally wear him or her down in the process. He rarely loses a rap battle at the local level. In 2012, Learic advanced to the second round of Black Entertainment Television's "Freestyle Friday" in Atlanta against national competition.

Generally, Learic exudes a calm, even-keeled demeanor, bordering on shyness. But the second he steps onstage to battle, he transforms. You can see it in his posture, which becomes almost frighteningly aggressive. You can feel the intensity in his rhymes, which spare no opponent. But even in this brutal arena, Learic relies more on wit than bravado.

"Rap is a genre that basically consists of dudes yelling at each other into microphones," says Boland. "So it's confrontational by nature. And one way to confront someone, especially in a battle, is by being as aggressive and nasty as possible."

Boland says there is another way, though: "You can be the smartest guy in the room. And in Devon's case, he usually is."

That blend of brain power, improvisational skill and passion translates to Learic's recording projects. Much of the Precepts record, in particular, was written in an opposite fashion from the way rappers typically write. Rather than coming up with verses and building hooks around them, the trio often developed the hooks on this record first; then Learic wrote lyrics to fit.

"Hip-hop is obviously very often verse-driven," says Coons. "But we started getting really collaborative and experimental with the hooks."

Coons, Maier and Learic worked on the record for 18 months, during which time they became friends. Coons and Maier began pitching the rapper hooks based on what was going on in his personal life at the time.

"Whether it was about a breakup or whatever else was happening with him, the hooks basically became writing prompts," Coons says. "I think he really thrives on that challenge, which is why he's such a great battle rapper, too. When the pressure is on, Devon has nowhere to go but to whatever is in the deep recesses of his brain."

"That record changed the way I think about rapping," Learic says. "It became less focused on rhyme schemes and the technical aspects and all about what we were saying, the stories we wanted to tell. The more you free yourself from the technical constraints of rapping, the more things flow, the more it just works.

"It's like acting," he continues. "Anthony Hopkins says his lines 1,000 times so he doesn't need to remember them, and just inhabits his character."

That approach carried over to the Write Brothers project. Indeed, there is a uniquely dramatic quality to Take Flight. And Learic's rhyme schemes, many cowritten with Vezina, can be wildly unconventional, sometimes even veering into spoken-word poetry.

"We approached it almost like you would writing the treatment for a screenplay," he says.

Learic points to the song "Moon Boots" as an example. The lyrics were inspired by Pierre Boulle's Garden on the Moon, a 1965 science fiction novel that takes place during the space race. In the book, the Japanese beat the Americans to the moon, despite having the technology to get an astronaut there but not back.

"The song is about an astronaut who is about to go to the moon," Learic explains. "But think about what else is going on at that time: Vietnam, race riots, the Kennedy assassination ... so much turmoil. So what if he gets up there after this hero quest, looks back at Earth, and a change happens?"

In the song, that change is reflected in two lines: "There's no people, / the Earth looks so peaceful."

"He realizes that it's people who are the problem," says Learic. "So what if he just chooses to live out the rest of his life with the oxygen he has left and doesn't come back?"

Vezina's evocative beats set the scene. As the astronaut prepares on launch day, he contemplates the minutiae of everyday life — traffic snarls, kids playing outside, drinking coffee in the morning — and the song cruises with manic, dubstep energy. But then our hero gets to space, and we feel his inner change occur in Vezina's serene, weightless beats.

"We approached it cinematically," says Vezina by phone from his West Coast home. "We spent hours shaping and reshaping it, like you would writing a film or a novel."

Vezina, who founded Upsetta Records in Burlington but now works as a producer in California, points out that every song on Take Flight was approached in a similarly no-holds-barred manner.

"We didn't put it in a box," he says. "We didn't say, 'This is how inventive or crazy it's gonna be.' We decided if we were going to write about something really deep, we should just do it and let whatever comes out, come out."

Vezina adds that Learic's training as an actor played a role in helping them do exactly that.

"I think it shows in the depth of the storytelling," he says. "In a perfect world, we would be in the same town or on the same coast and be able to work on an in-depth stage show, where the audio and visual are one thing."

Learic has recently left Burlington to pursue acting once again in New York City. He says he'll still be heavily involved in Vermont hip-hop, but he feels the need to reconnect with his theater roots. So might Learic's next artistic venture be, say, a hip-hopera? Don't rule it out.

"Actually," he reveals, "I've been working on a C.S. Lewis-inspired hip-hop musical for a while now."

INFO

theaztext.com, facebook.com/theprecepts, soundcloud.com/the-write-brothers

The original print version of this article was headlined "Novel Concepts"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Music Feature, rap, hip hop, Learic, Aztext

More By This Author

About The Author

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Speaking of...

-

With 'GUMBO,' Rapper and DJ Fattie B Unites a Scene and Makes the Record of His Life

Nov 23, 2022 -

Video: Benjamin Lerner and Joshua Sherman Team Up to Make Music About Recovery

Jul 15, 2021 -

Rapper Benjamin Lerner Champions Recovery on Debut Record 'Clean'

Jul 14, 2021 -

Best hip-hop artist or group

Jul 31, 2019 -

Vermont Rapper/Comedian Omega Jade Finds Catharsis in Humor and Hip-Hop

May 15, 2019 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Soundbites: Burlington Record Plant On the Move Music News + Views

- 2. On the Beat: New Music From Phish and a Family Folk Affair in Grafton Music News + Views

- 3. Three Quick-Hit Reviews of Local Albums Album Review

- 4. Soundbites: Umphrey's McGee Loves Burlington Music News + Views

- 5. Community Garden, 'Me vs Me' Album Review

- 6. Frankie White, 'brain dead' Album Review

- 7. Six Quick-Hit Reviews of Local Albums Album Review

- 1. Legendary Vermont Saxophonist Joe Moore Dies Music News + Views

- 2. Soundbites: Trouble & Together at the Flynn Music News + Views

- 3. Soundbites: Burlington Record Plant On the Move Music News + Views