Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Pipe Dream? It's Decision Time on Burlington's Long-Simmering Proposal to Heat Buildings With Wood-Fired Steam

Published September 27, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 4, 2023 at 10:09 a.m.

About 75 percent of the heat used to make steam at the 50-megawatt facility escapes through the plant's soaring smokestack and its smaller twin cooling towers, which release billowing white plumes into the sky above the Intervale plant.

In 2007, Schultz cofounded a citizen's group called Burlington District Energy System. Its goal: harness the wasted heat and pump it into a network of pipes to warm homes and businesses so that they will no longer rely on fossil fuels. Schultz has been such a staunch advocate that a former general manager of Burlington Electric once called him the "spiritual leader" of the effort.

But as a moment of truth looms, Schultz is having a crisis of faith.

This summer, smoke from Canadian wildfires darkened skies above much of the U.S. A city in Hawaii burned to the ground. Catastrophic floods ravaged Vermont. Like people worldwide worried about the climate crisis, Schultz watched in horror.

"When I look at what's happening in the world, I mean, holy shit!" said Schultz, 81. "Burning wood is just not the thing to do. The whole thing is absurd."

Since the plant opened in 1984, city officials have taken the position that burning trees sustainably harvested from local forests is a climate-friendly alternative to the way most electricity in the U.S. is produced — by burning fossil fuels such as natural gas, coal and oil. And it takes advantage of a renewable fuel source: wood.

But today, as climate scientists warn of the urgent need to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, a growing number of experts and environmental activists argue that burning trees and other forms of organic material, collectively called biomass, is also bad for the climate.

The shift in thinking has heightened the scrutiny of both McNeil's operations and its potential expansion. Climate scientists held a symposium in June to urge Burlington to rethink its reliance on burning trees for electricity. Clean energy advocates proposed state legislation that would have prevented Burlington from calling McNeil's power renewable. And climate activists have held loud rallies demanding that the city shut down the plant. Last weekend, protesters crashed Burlington Electric's Net Zero Energy Festival, which had been billed as "a day of outdoor fun for the whole family to share Burlington's Net Zero Energy vision." Protesters paraded through the celebration with a huge black snake puppet representing the steam pipeline.

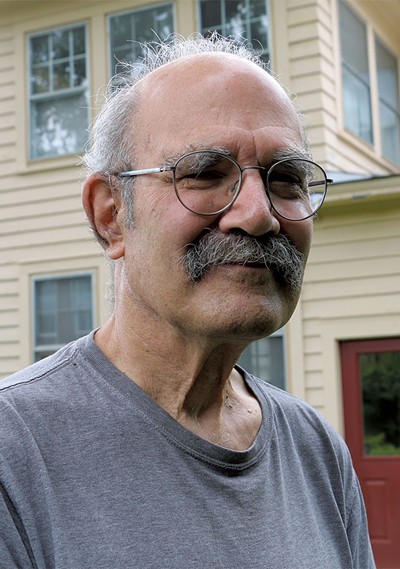

The debate has intensified as the Burlington City Council inches closer to a pivotal decision on a complex, $42 million proposed project that would pipe steam from McNeil to the University of Vermont Medical Center.

Project backers hope to supply the hospital with a renewable, climate-friendly heating source to displace the huge volumes of natural gas — "fossil gas" to use critics' term — that the hospital consumes today. And they note with suspicion that Vermont Gas Systems, which would lose one of its biggest customers, supports the project and would partly own the distribution system.

But questions about McNeil's true climate impacts, the potential of climate-friendlier power options and the project's soaring estimated costs all threaten to undermine the case for district energy, leading to a do-or-die moment for the city's highest-profile climate solution.

If the project can't overcome the looming financial and political hurdles, Mayor Miro Weinberger's aggressive goals to become a "net-zero" city by 2030 could prove significantly harder to reach. The term refers to removing as much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as is being added to it — which is sometimes referred to as being "carbon neutral." Burlington hopes to reduce and eventually eliminate fossil fuel use in the heating and ground transportation sectors, and the project has for years been a key component.

"This is it. We are at the go, no-go decision," Weinberger said. "We are either going to emerge from this intense period of analysis, investment and work and finally find a path to get this built, or we're done."

Carbon Counting

Since McNeil's earliest days, Burlington has been considering ways to make it more efficient. At least six district energy studies over the years have gone nowhere. Yet the current proposal to pump McNeil's steam to heat the hospital has gotten far closer to fruition than past efforts.

"Every single study that's ever been conducted on this has been a feasibility study," Darren Springer, the electric department's general manager, said. "This is an engineered project that's ready to go and actionable."

Well, it's not totally ready to go. The project still needs a contract with the hospital, council approval and an Act 250 permit.

Burlington City Council work sessions on the project have twice been postponed to give more time for contract negotiations between BED and the hospital, which are now in their third month. The closed-door talks, which involve financial terms and the structure of the complex deal, are "dynamic," Springer said. The hospital would buy the steam, providing revenue that would help pay for the system.

Springer said he hopes to have an agreement to bring to the council by October 10 so he can publicly share the latest details and financial terms.

"If we are able to bring it forward, that will be an exciting moment," he said.

The project's recent progress has fired up climate activists. They worry that a major investment would extend the operation of a nearly 40-year-old plant they say contributes to the climate crisis.

"We fundamentally do not believe that we should be giving a lifeline to the McNeil facility," said Elena Mihaly, director of the Vermont chapter of Conservation Law Foundation. "It's a dirty facility that is nearing the end of its useful life."

Mihaly and others argue that McNeil and Ryegate, the other wood-fired electric power plant in the state, should be phased out in favor of clean energy such as wind, solar and hydroelectric. Those sources already fulfill 68 percent of Burlington's energy needs, while McNeil kicks in 32 percent. The city's power portfolio has enabled officials to proclaim since 2014 that it uses 100 percent renewable energy.

At the heart of the issue is a wonky but fierce debate about how harmful biomass electricity is to the climate. Backers note that carbon from biomass energy theoretically can be recaptured if new trees are allowed to mature. Yet a growing number of climate scientists warn that burning trees for energy is creating a carbon debt that future forests will be unable to pay.

"We know we don't have time on our side," Mihaly said. "From a climate perspective, we have no choice but to look at how we move past burning wood for electricity in Vermont."

Meanwhile, leading climate accounting organizations consider biomass energy sources such as McNeil to be carbon neutral under certain conditions. Burlington Electric contends that McNeil meets the standard because the wood chips it burns are sourced from healthy forests that suck up more carbon than logging removes.

Either way, burning trees produces a huge amount of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas contributing to the climate crisis. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, McNeil spews about 400,000 tons of the gas every year, more than any other energy facility in the state. That doesn't include additional gas released by the machines that harvest, process and transport the chips to McNeil.

The argument for biomass energy being carbon neutral is that the fuel comes from part of the natural, aboveground carbon cycle, as opposed to the fossil carbon that humans have been extracting from the ground since the 1800s.

Climate scientists and groups such as 350.org, Third Act, Stop VT Biomass and Standing Trees argue that forests need to be protected to store as much atmospheric carbon as possible.

"UVM Medical Center is one of the state's great prizes," environmentalist Bill McKibben said in a statement. "I hope it supports energy sources — sun and wind — that neither foul our lungs nor lead to the climate disasters that their nurses and doctors must treat. A lifeline for McNeil isn't really a lifeline for Vermonters."

Councilor Gene Bergman (P-Ward 2) has long been a supporter of the district energy project, but the June biomass symposium and other research have changed his mind. He lives in the Old North End and can see McNeil from outside his home.

"I don't believe we should be expanding the burning of fuels — in this case, biomass — in a climate emergency," Bergman said. "Put simply, we need to stop burning stuff."

Supporters of the district energy plan stress that the plant, which is jointly owned by the electric department, Green Mountain Power and the Vermont Public Power Supply Authority, plays a vital role in the stability and cost-effectiveness of the state's electricity grid.

Unlike wind and solar, which are intermittent, McNeil can be turned on anytime it's needed, including in the dead of winter, and run virtually nonstop. (It is in use about 60 percent of the time.) Without the plant, Burlington — and the state — would be more dependent on electricity purchased from the grid, largely generated elsewhere in New England from fossil fuels, project backers argue.

"Would we build it today? Probably not," Councilor Mark Barlow (I-North District) said of the plant. He sits on a committee that's been reviewing the district energy proposal. "But we have it, and to me, it seems we need to do what we can to make McNeil better."

Hospital or Bust

The current district energy project is a slimmed-down version of one proposed in 2017. That iteration would have sent hot water from McNeil to the hospital and possibly parts of the UVM campus before looping downtown. It would have hooked up 46 buildings with a combined 4.2 million square feet of space. The medical center, a handful of buildings at UVM, and downtown properties such as city hall, Hotel Vermont and the future CityPlace Burlington project were all considered potential customers.

Cost estimates ranged from $39 million to $53 million, and the project promised to reduce Burlington's greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent over 30 years. Like previous versions, however, the plan stalled without backing from building owners.

The process nevertheless proved valuable because it showed that 70 percent of the potential greenhouse gas emission reductions could come from a single customer: UVM Medical Center. Eager to keep the project alive, the city asked a previous consultant, Ever-Green Energy from St. Paul, Minn., to retool the plan to focus on the hospital's heating needs.

"It's not an easy project," said Michael Ahern, the company's senior vice president of system development. "There's a lot of different folks working to try to make this happen."

In 2022, Burlington Electric, Ever-Green and Vermont Gas formed a nonprofit called Burlington District Energy, helmed by Springer, that would build and own the system. Neither taxpayers nor ratepayers would be on the hook for it.

The main players driving the project know each other well. Vermont Gas president and CEO Neale Lunderville spent four years as Burlington Electric's general manager after Weinberger appointed him to the post in 2014. At the time, the mayor tasked Lunderville with getting district heating done. That didn't happen, but Lunderville, who landed at Vermont Gas in 2020, remains a close confidant of the mayor's.

"My duty here is to do what's in the best interest of the customer and is aligned with our company values," Lunderville said.

Weinberger also has a close relationship with UVM Medical Center president and COO Stephen Leffler. They worked jointly on COVID-19 policies during the pandemic, appearing on webcasts together.

A hospital spokesperson did not make administration officials available for an interview. In a statement, the hospital took the position that it "remains interested and engaged in this project" and is analyzing the financial complexities.

"Our goal throughout this process continues to be ensuring that we make informed decisions that put our patients first and remain true to our commitments to the communities for which we care, while also continuing to act as good stewards of limited healthcare dollars," the statement reads.

Leffler, meantime, has personally endorsed the project. In May, he wrote a letter to Vermont Treasurer Mike Pieciak, encouraging the state to approve a $25 million low-interest loan for it.

"The project would benefit our operations and community by advancing local and state climate goals, supporting energy innovation, and fostering strong partnerships to support the local economy," Leffler wrote.

Project backers appear to be doing everything they can to get the hospital on board. The pipeline, originally designed to connect to the hospital near the emergency department, was rerouted to the eastern edge of the property to accommodate future expansion plans, Ahern said.

But both building and borrowing money have gotten much more expensive in the past few years. In 2020, Ever-Green estimated that the streamlined project would cost $16 million. Inflation, supply chain challenges and a sharp rise in interest rates have since caused the price tag to balloon to $42 million, Ahern said.

The project was banking on the $25 million state loan, with the balance coming from $12 million in tax-exempt bonds and a $5.2 million federal grant lined up by former U.S. senator Patrick Leahy.

Following the July floods, however, the state is prioritizing loan applications for housing projects, according to a spokesperson for the treasurer. Springer acknowledged that the delay in obtaining loan funds could increase borrowing costs, but he couldn't say by how much. He acknowledged that the financial challenges represent "headwinds" for the project but said they were manageable.

The contract with the hospital is the biggest sticking point. But the gas company, which could stand to earn "clean heat credits" for the project under a new state program being developed, could sweeten the pot with financial incentives for the hospital. And the city holds some leverage, too.

Burlington has a new carbon-pollution impact fee, which voters approved and is soon to become law, that would penalize the medical center if it sticks with fossil heat. The hospital could face fees for failing to make eco-friendly heating upgrades. As the hospital grows and replaces its systems, the mayor noted, "they will be facing a very substantial carbon pollution fee if they continue to rely on fossil fuels for that energy."

Waste Not

click to enlarge

- Luke Awtry

- Engineer Paul Pikna pointing out equipment at the McNeil Generating Station

When it's operating, McNeil burns about 74 tons of wood chips hourly in a massive furnace that transforms water into a potent plume of superheated steam. That steam, which emerges from the boiler at 950 degrees and pressure of 1,250 pounds per square inch, is forced through a massive turbine generator at the heart of the facility.

Ascending a steel ladder on a recent tour of the nine-story plant, engineer Paul Pikna pointed through a tangle of pipes, ducts and valves on the underside of the turbine. Deep in those industrial innards, a new high-pressure pipe would be added to siphon off some steam before it could generate electricity. That steam would be piped out of the building and to the hospital. (A 10-megawatt electric boiler would be installed to ensure that the steam could be delivered even when McNeil is not operating.)

The diverted steam would reduce the plant's electricity-generating capacity by about 3.5 megawatts — or 7 percent. While power sales to the grid could drop, the hospital would provide a new stream of revenue that would benefit Burlington Electric, Springer said.

The steam would travel a mile and a half through a 12-inch pipe buried in an insulated trench beneath city streets and sidewalks to the east end of the medical center's campus.

A smaller four-inch distribution line could supply steam to a handful of nearby university buildings. But there is no plan to hook up main campus buildings because the university hasn't shown an interest, Springer said. The university runs its own steam-based district energy system, which is powered by natural gas with an oil backup.

The steam from McNeil would enter the hospital's distribution system, allowing it to take its natural gas boilers offline for much of the year. Those boilers would always be available as a backup power source in the event that McNeil goes offline, or on cold winter days.

After the hospital's heating system used the steam, it would naturally condense into water and flow through a separate pipe back toward McNeil. The Intervale Center or nearby commercial operations could use the water, which would still be hot, to heat buildings, but there are no agreements for that yet.

Once the water returns to McNeil, a device would capture some of the waste heat from the smokestack to reheat the water, which then would flow into the boiler to be fired into steam once more. That in turn means less wood would need to be burned. This could increase the efficiency of the plant from 26 percent to 29 percent.

That's "nothing to sneeze at," Springer said. But Schultz called the improvement paltry.

He and his fellow committee members have vigorously debated whether to support the current version of the project. Earlier this summer, Schultz said he'd come to agree with those who think McNeil should be shut down.

After meeting with Springer and Lunderville to learn more, however, he and other committee members have softened their position. The group now says it could support the project on three conditions. One is that the city commits to hiring an independent auditor annually to ensure that McNeil's wood harvests are sustainable.

McNeil purchases more than 88 percent of its chips from logging jobs in Vermont and New York. The majority are from "tops and limbs" of trees that were cut down for other reasons, such as lumber or firewood, according to the plant's chief forester, Betsy Lesnikoski. Critics are skeptical, noting that the electric department's own contracts require the delivery of "whole tree chips" and allow clear-cutting of up to 25 acres.

Another condition: The city must install equipment using waste heat to dry the wood chips before they are burned. The 400,000 tons of chips used annually are mostly unseasoned, slower-burning green wood.

A 2019 study estimated that such a project might cost $4 million. But it could reduce the amount of chips burned by roughly 7 percent and save nearly $800,000 per year. Officials never pursued the project because low electricity prices at the time didn't justify the investment, Springer said.

"The economics of doing this now are much stronger than they were back then," said Springer, who agrees the idea merits new analysis. But Schultz said he's not interested in more studies, only in a binding commitment to do it.

The group's final condition: A new citizens' group must be formed to ensure that the city follows through on its promises.

Said Schultz: "All of us are too damn old to be doing this stuff anymore."

Steaming Mad

click to enlarge

- Katie Futterman

- Climate activists protesting at the McNeil Generating Station in July

Environmental activists have been turning up the heat on city leaders all summer. About 40 people gathered outside McNeil one Saturday in July to protest the district energy plan. "Temps are Rising and So Are We," read one sign. "Use Our $ for Climate Solutions," said another.

"It's a depressing topic these days," activist Catherine Bock told Seven Days.

Speakers who urged the city to close the plant argued that burning trees is worse than burning coal. They said they worry future generations will face the climate calamities that have already begun.

"What we're talking about are trees," Geoff Gardner said. "Which should be either lying down dead in the forest or standing up tall and alive in the forest, where they do a tremendous amount of good."

Other speakers mocked the electric department's reliance on a 40-year-old plant and accused the department of greenwashing, or falsely touting its energy as climate friendly.

Lena Greenberg said the public isn't being told the truth about climate change, declaring: "I'm standing right in front of one of those lies."

Project opponents note that there are other ways to reduce the hospital's fossil fuel use: geothermal, reusing waste heat from its existing system or installing electric boilers.

Jay Peak Resort, for instance, with 178 hotel rooms and the region's largest indoor water park, has huge heating needs. It recently installed a $1 million electric boiler that is expected to reduce the resort's propane use by 60 percent, saving an estimated $250,000 per year.

click to enlarge

- Kevin Mccallum ©️ Seven Days

- Activists outside the June biomass symposium in Burlington

In Burlington, the Hula campus in the city's South End uses geothermal heating, something officials have considered for city buildings, according to Weinberger.

But neither of those options seems to be viable for the hospital, Springer noted: Geothermal systems can't produce steam, and electric boilers can be expensive to run.

It's not clear how thoroughly the hospital has explored heating options or whether it considers McNeil its best bet. Instead of answering that question, a hospital spokesperson listed some of the other ways the facility has improved its energy efficiency.

Considering a range of energy alternatives is important, Springer said, but opposing an actual, shovel-ready climate solution in favor of hypotheticals is an example of making the "perfect the enemy of the good."

Burlington has an aggressive plan to get to net-zero carbon emissions in buildings and transportation by 2030. The road map relies on weatherizing homes and businesses, heating them with electricity, encouraging conservation, and accelerating the shift to electric vehicles. The district energy plan at the hospital would reduce fossil fuel use in commercial buildings citywide by 16 percent, the biggest single cut to fossil fuel use in Burlington buildings, according to estimates.

In an interview last week, Weinberger expressed strong support for the project but also resignation that it could be snuffed out. If it is, the city stands ready to help the hospital explore other ways to limit its fossil fuel use, the mayor said. "We need to do that because it's basically the biggest economic entity in the city, and they need to participate in getting to net zero, whether with this project or without it," he said.

Weinberger agreed the district energy decision is a nuanced one. He said he is "persuaded by the argument that we do ultimately want to move away from combustion and from biomass." At the same time, doing so without viable alternative energy sources would lead to more fossil fuel use, he said.

That's a convincing argument for Barlow, the city councilor, who said he'd likely vote for the project, if and when it comes before him.

"The thing about governing is, there aren't clear choices a lot of times," he said. "There's no black and white, or good and bad. It's murkier than that. And this is one of those times."

Katie Futterman contributed reporting.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Environment, Climate Crisis, Burlington, Joseph C. McNeil Generating Station, McNeil Plant, wood heat, biomass

About The Author

Kevin McCallum

Bio:

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

More By This Author

Latest in Environment

Speaking of...

-

New Marker Provides a Window Into the History of Burlington's Battery Park

May 8, 2024 -

Queen City Café’s Biscuits Are Hot at Burlington's Coal Collective

May 7, 2024 -

Abbey Duke Replaces Emma Mulvaney-Stanak in Legislature

May 6, 2024 -

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate

May 1, 2024 -

Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help

May 1, 2024 - More »

find, follow, fan us: