Published June 28, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 12, 2019 at 3:17 p.m.

The human cost of Vermont's opiate crisis was on display at a recent SubStat meeting at the Burlington Police Department.

Chittenden County State's Attorney Sarah George and Burlington Police Chief Brandon del Pozo sat alongside street cops from Essex, Burlington and Winooski at a boardroom table. There were no snacks or bottles of water, and little chitchat.

The group immediately got to work, studying a spreadsheet of every overdose and drug-related crime in the area for the past month, projected onto a screen.

One by one, they went through the cases to compare notes and strategize how to help the people they encountered.

They brainstormed ways to get a wealthy University of Vermont student in the throes of a heroin addiction away from her boyfriend, a fellow addict who has been controlling her. They talked about an Essex woman who lost custody of her two children and left a slurred message with the police department asking for help with her addiction.

A Winooski police officer reviewed his team's response at a downtown apartment where a drug user had overdosed and been revived with Narcan before the EMTs arrived. He refused a ride to the hospital — and further treatment. The officer asked George to intervene.

"He isn't going to respond to us, but maybe you can help," suggested Lt. Michael Cram. As a state's attorney, George can bring charges — or at least threaten to — in an effort to scare the man straight.

Sitting silently in a corner of the room were two men dressed in civilian clothes: Eric Fowler, a Burlington police crime analyst, and Sam Francis-Fath, Chittenden County Opioid Alliance data manager, are tasked with creating reports and databases about the police response to opioid-related crime.

Although the duo didn't have much to say that day, they've been instrumental in calling out a problem less obvious than the ravages of opioid abuse. They say their work is made more difficult by a dearth of information about doctor-prescribed opiates — a primary cause of the epidemic. Four out of five new heroin users had previously abused prescription pain relievers, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration reported in 2013. Pain meds likely launched some of the tragedies being discussed that day in the ninth SubStat meeting since February.

The state makes only a tiny sliver of drug-dispensing data available to the Vermont public, and it's out of date.

Access to more and timelier data "would give us a much more clear picture of what's going on in the universe of prescribing practice," said Francis-Fath. "There is an assertion that doctors have [gotten] it together and stopped overprescribing. It would be nice to have data to back that. Everyone is wondering. We could know if what we're doing is effective."

Earlier this year, the two data guys had a breakthrough. Frustrated by how little the state Department of Health made available, Fowler and Francis-Fath dove into federal Medicare data, which is public information.

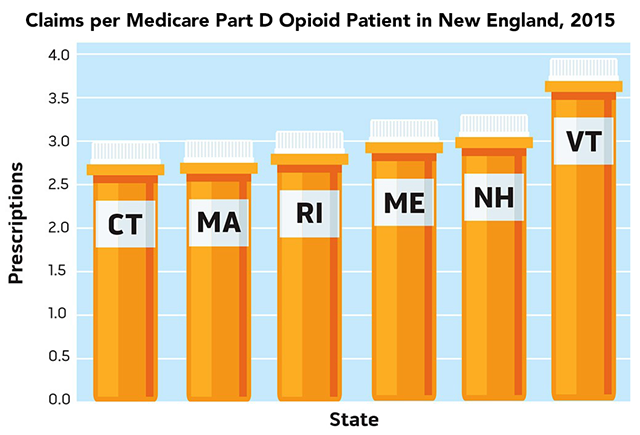

They found that Vermont physicians wrote 17 percent more opiate prescriptions per patient than their counterparts in other New England states.

Fowler and Francis-Fath published their findings in a report that Burlington officials have been circulating.

Alarming as it was, that glimpse didn't show the whole picture. Only 14 percent of insured Vermonters have Medicare Part D plans, and they are generally seniors and others on Social Security. What is the rest of the population picking up at the pharmacy? Only the state health department knows; since 2009, its Vermont Prescription Monitoring System has kept track of statewide drug distribution. But that info is not available to the public, researchers, law enforcement or, in some cases, its own investigators tasked with regulating doctors.

Del Pozo, Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger and some other prominent officials say it's time for that practice to change. In interviews with Seven Days, they called for medical providers and the Department of Health to become more transparent by sharing prescribing information with the public.

It will be impossible, they say, to solve the opiate crisis without more scrutiny of doctor behavior. They believe the VPMS should be opened to pressure doctors to write fewer and shorter scripts.

"We all feel that we're making progress in understanding the dangers of overprescribing," Weinberger said in an interview in his office. "We all want to see that continue, and having data beyond Medicare would be helpful."

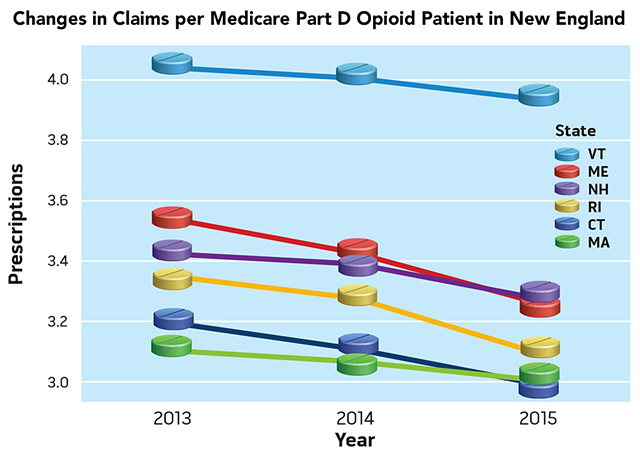

Seven Days recently conducted an independent analysis of three years' worth of Medicare prescriptions that included 2015 data released in May — the most recent numbers available. It showed no substantial decrease in prescribing rates, even after then-governor Peter Shumlin made Vermont's opiate crisis the focus of his State of the State address in January 2014.

Last year, Vermont set a state record with 105 opiate overdose deaths, prompting cries of concern from government officials and private citizens alike. The state is on pace to set a new record this year, according to 2017 first-quarter data from the Vermont health department. In Burlington, both fatal and nonfatal opiate overdoses are on track with last year's tallies.

"Given where we are now, it's reasonable to reassess if the limitations we built into [VPMS] still make sense," del Pozo said. "Right now, the only truly reliable and recent number we have is the death toll. Everything else we have is an estimate."

Policing Doctors

Are some doctors prescribing far more opiates than others? Are certain drugs more likely to be subject to overprescription? Have people in certain medical specialties curtailed their use of opiates, while others have not?

The answers to many of those questions are in the 8-year-old VPMS, a statewide database of all prescriptions issued by Vermont-licensed pharmacies.

The database was designed primarily to allow doctors and pharmacists to keep an eye out for patients who were "doctor shopping" to fuel their addictions. It is also billed as a tracking tool to allow health experts to observe statewide trends in prescribing.

Annual reports on the Department of Health website offer some summary information: Vermont doctors issued 601,506 opiate prescriptions in 2015, almost one script per state resident. Overall, one in five Vermonters received a prescription for at least one opiate that year. The report includes graphics that break down opiate recipients by county, age group and gender.

But that's the extent of what's publicly available from the VPMS — for now.

A thicket of rules and laws safeguards the database and forbids its release under the public records act. Only a handful of health department employees can log in.

Calls to increase access in 2012 brought the VPMS before the legislature. The debate revolved around two primary concerns: the confidentiality of doctor-patient relationships and whether police officers should be able to see the database without a warrant, as former public safety commissioner Keith Flynn was advocating for at the time.

"People wondered, was it a medical tool? Was it a clinical tool? Was it a law enforcement tool?" former health commissioner Dr. Harry Chen recalled.

"The legislature came down really, really strongly that it was going to be a clinical tool," said Chen. The police were frozen out. "Now we're bringing in another question — should this be a publicly available database? But that was never what it was intended to do. Doctors really don't want the state to get in between them and their patients."

Since they lost the battle for access five years ago, police have not formally challenged the legal protections of VPMS. But, in a recent interview, Commissioner of Public Safety Tom Anderson said he, too, would like to see the database opened, in at least some fashion, for study and evaluation by both regulators and the public.

"We have to look at prescribing practices," Anderson said. "I concur with Chief del Pozo that with the prescription monitoring program, some additional transparency would not necessarily be a bad thing. The doctors are a big part of the solution to the problem. We've just got to stop prescribing as much."

Jackie Corbally, a former health department employee who worked on VPMS and is now Burlington's opioid policy coordinator, was more direct.

"When the system was crafted, we were not in the middle of an epidemic," Corbally said. "[VPMS] is sitting on a large wealth of information, and any resource that would help us further understand this epidemic should be forthcoming."

Attorney General T.J. Donovan agreed.

"We need the data, because the data tells the story," Donovan said. "It's not about going after doctors; it's about education and awareness. And if there's outliers out there, we need to know."

Law enforcement officials say they have little interest in launching investigations of doctors. There are no recent Vermont cases of "pill mills" — doctors or pharmacists dishing out drugs at enormous rates for little patient gain — and they have enough to worry about with street dealers.

"It would be helpful to see the data, but I can't see it kicking off a criminal investigation," Anderson said. "It would be more important, if you saw an outlier, for somebody to go talk to them."

In fact, that's precisely how doctor policing works in Vermont. The Vermont Board of Medical Practice handles regulation of physicians. Board members, appointed by the governor, include a mix of professionals and civilians charged with granting licenses to practitioners and making sure providers are following the rules.

A review of cases brought by the medical board since 2013 shows that relatively few have gotten into trouble for overprescribing, and all of those cases involve doctors accused of diverting pills for their personal use.

One example: Former Burlington family care doctor Cynthia Haselton lost her license for three years in 2012 after she wrote 288 prescriptions for drugs including Adderall and Vicodin to fake patients — and obtained the drugs for herself.

But the medical board, which has two full-time investigators, is designed to be reactionary, not proactive, in monitoring the state's 4,500 licensed doctors. It responds to complaints filed against them.

Between 2011 and 2015, it averaged 197 investigations and nine disciplinary actions a year. Most of the latter were settlements; only 11 cases between 2012 and 2015 resulted in a doctor temporarily or permanently losing his or her license.

While overprescribing is among the board's top concerns, investigators do not have access to VPMS, according to executive director David Herlihy. They can review VPMS data only after they receive a verified complaint and formally launch an investigation. But it is extremely rare for a patient or member of the public to complain about a doctor being too liberal with prescribing medications.

In fact, Herlihy said, it is more common to receive complaints from patients who allege that doctors unreasonably withheld medication from them.

"Could we find more cases if we had the ability to just sift through the data and VPMS? Probably," Herlihy said. "But the board hasn't been pushing to get that. There are strong concerns about the magnitude of the opioid problem. There are also strong concerns about privacy. I think Vermont has done a pretty good job of balancing the competing interests here."

Only one individual in the Department of Health can take a proactive step against an overprescribing doctor: the commissioner. He or she can look at the VPMS, according to the law governing the database, and make contact with any suspected abusers.

Seven Days filed a public records request for correspondence between commissioners and doctors since 2012 under that provision. No such records exist, the department's attorney responded.

Chen, who retired in March after six years, said he referred approximately one case a year to the medical board — and sometimes spoke to the doctors involved.

His successor, Dr. Mark Levine, said he has monitored VPMS data but has not made referrals to the board or reached out to any doctors. Levine said he opposes increasing the availability of VPMS data for fear it would lead to "public shaming" of doctors.

Too Many Pills

Seven Days analyzed Medicare data from 2013, 2014 and 2015 and found that Vermont doctors prescribed their opiate patients enough drugs to last 82 days — more than any other New England state. Doctors in Massachusetts prescribed for 63 days; New Hampshire, 67 days.

Vermont patients also tended to get more scripts than patients in the other states.

"The data suggests clearly that Vermont seems to be an outlier among New England states in pure volume of prescriptions that are being made for the population," del Pozo said.

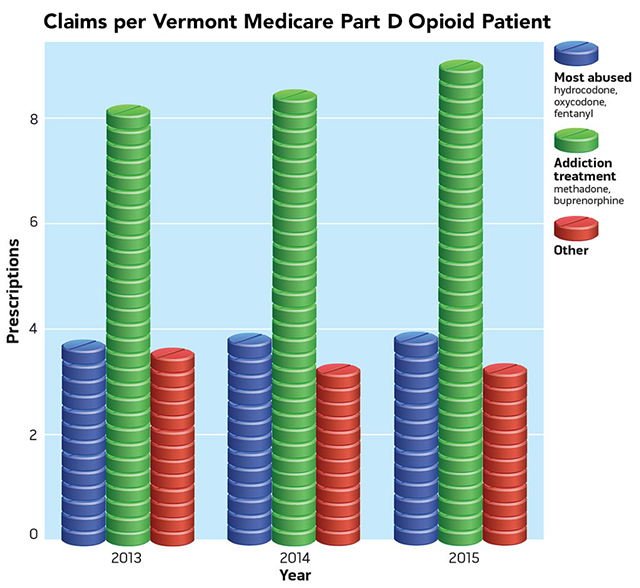

During the same period, Seven Days' analysis found, the number of days for which Medicare patients were prescribed the most-abused opiates — including oxycodone and hydrocodone — increased slightly in Vermont.

"In 2015, enough painkillers were handed out in Vermont to give every man, woman and child a bottle of 100 pills," then-governor Shumlin said as he signed into law a bill that restricts prescribing — effective this July.

The Medicare data shows that, in the same year, prescribers doled out 2.9 million days' worth of opiates to Vermonters in the program, who then numbered about 90,608.

Seven Days reached out to Vermont's top 15 prescribers of opiates in the Medicare program during that same period. Three of them agreed to talk.

Former University of Vermont psychiatrist Brian Erickson said he was not surprised that he had the most opiate claims under Medicare in 2013 and 2014. Erickson worked at a UVM Medical Center pain clinic and treated patients who had already been prescribed opiates by their primary care doctors.

If doctors contributed to the opiate epidemic by prescribing painkillers, they did so unwittingly, said Erickson, who left Vermont at the end of 2015 to take a job in Minnesota.

Erickson said that, in the 1990s, the medical community was focused on eliminating pain, which had been dubbed "the fifth vital sign." Doctors were encouraged to prescribe relatively new opiate drugs such as OxyContin, which were heavily marketed by pharmaceutical companies and believed to be safe.

"There was a belief that patients deserve to be treated for pain," Erickson said. "There was a sense in medicine [that] if patients said they had pain, then you would use opioids and be relatively comfortable with it. The pendulum has swung from doctors being concerned they would be in trouble for undertreating."

Erickson said he was keenly aware of the risk of creating addicts with prescription pills and took steps to prevent patients from abusing the medications while working in Vermont. He said he explained the dangers of the medications with all of his patients, subjected them to random pill counts to make sure they weren't taking more than the allotted dosages and switched medications if a patient had suspiciously "lost" any meds.

"Doctors don't like to be in the role of police and detective and judge, but I would spend a lot of time talking to the patients and their families and say, 'Look, these opioids can be helpful, but there are concerns,'" Erickson said.

He said most of his patients who were on long-term opiate prescriptions led normal lives, holding jobs and raising their families.

"You have to pay attention to people," Erickson said, "but it's a myth that it's terrible for all of them."

In fact, rationing opiates for pain patients could drive them to seek relief in more dangerous environments, said Cheryl Gagnon, a top Medicare prescriber who until recently worked as a physician's assistant at the UVM Medical Center pain management center in South Burlington.

"The bottom line is: People are going to go to the street because they're going to be in so much pain," she said.

Ten years ago, Windsor physician Clifton Lord took on chronic pain patients that other doctors rejected. But in the past couple of years, he's become increasingly concerned about consequences of overprescribing and, in some cases, has opted for physical therapy and acupuncture instead.

"I was careful before — I wasn't taking on all comers — but I've become even more discerning and discriminating," Lord said. "I have changed a lot. I want to treat people with things that work and don't make things worse. Anybody who takes opiates eventually becomes dependent physically."

UVM Medical Center chief medical officer Stephen Leffler summed up the physicians' perspective: "No provider ever started prescribing to make someone an addict."

More than a year ago, the UVM Medical Center started keeping track of the prescribing behaviors of its doctors — not just at the hospital but throughout its entire network of medical centers.

The act of compiling that data and sharing it with employees has already sparked a decrease in opiate prescribing, said Leffler.

UVM Medical Center doctors prescribed 7 percent fewer opioids in the first quarter of 2017 than in the same time period a year ago and managed to cut the tally further in the second quarter of 2017, according to a hospital report.

Vermont's second-largest health care provider, Dartmouth-Hitchcock medical center, took a different approach: It looked at variations in prescribing practices related to specific medical procedures. By alerting doctors to the disparities, the Lebanon, N.H., hospital recently reduced post-op opiate prescriptions for five outpatient operations by 53 percent, according spokesman Mike Barwell.

Are such efforts making a difference? Until data professionals such as Fowler and Francis-Fath can access the VPMS, it's hard to say.

"We recognize we have an opiate crisis in the state of Vermont, and we're absolutely committed to being part of the solution," said Leffler. Hospital representatives have been meeting regularly with police and other health officials to discuss trends and brainstorm strategies. Those monthly gatherings, called CommStat, have been off-limits to the media.

Leffler said he believes that doctors throughout Vermont have woken up to the dangers of overprescribing and will steadily reduce the number of pills they dole out in the years to come.

Levine, the new health commissioner, cited a recent measure that suggests opiate dispensing may be on the decline in Vermont: He said the American Medical Association just released a 50-state report that says statewide retail prescriptions of opiates dropped 10 percent in 2016, twice as steeply as the national average of 5 percent.

The former practitioner of internal medicine said that word of the opiate crisis made him less inclined to prescribe the drugs — and his patients less likely to want them.

Offered opiates, "Many patients would say, 'I'm in pain, but no, no, I don't need them.' My colleagues had similar experiences," Levine said.

The new health department rules going into effect July 1 should nudge doctors even further in that direction.

The wide-ranging standards, which were two years in the making and opposed by some doctors, will forbid the use of opiate painkillers to treat minor injuries or procedures, cap the number of pills doctors are allowed to prescribe for more serious injuries, and require doctors to educate patients about the risks of opiate addiction.

"The conversation really changed over the past year," Leffler said, noting that "many, many providers" now want the Department of Health to use the VPMS to keep their colleagues in line.

Almost a decade after Vermont started keeping a half-closed eye on the ways in which medical professionals contribute to the opiate crisis, "We are more open to transparency," he said.

Opioids Prescribed Through the Medicare Part D Program in Vermont, 2013 to 2015

Note: Does not include numbers for prescribers who wrote fewer than 11 prescriptions for a drug in one year.

Source: Medicare Part D prescribing data,

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Crunching the Medicare Numbers

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services releases summary data on the prescribing habits of medical practitioners for their Medicare Part D patients — but its data is not absolutely complete. Doctors with fewer than 10 opiate-receiving patients, or who wrote fewer than 10 prescriptions for opioids over the course of the year, show up as blanks in the database. For our analysis, Seven Days digital editor Andrea Suozzo filled in some of those using the median of possible patient numbers. She also removed spreadsheet rows of data containing more than one blank field. This eliminated some low-prescribing providers from the data — but allowed us to calculate prescribing practices for the program as a whole.

Read more about our process and methods here.

Correction, June 28, 2017: An earlier version of this story misspelled data analyst Sam Francis-Fath's last name.

Correction, June 29, 2017: This story erroneously cited a statistic from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It has been removed, and a figure from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration added in its place.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Just What the Doctor Ordered"

More By This Author

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

Running to Raise Money for Opioid Recovery, Salisbury's Chip Piper Completes 10 Marathons in 10 Days

May 28, 2024 -

Driven by Grief and the Hope of Helping Others, Chip Piper Aims to Run 10 Marathons in 10 Days

May 8, 2024 -

Outgoing Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger Holds Court — for the Last Time — at ‘the Bagel’

Apr 3, 2024 -

Burlington Will Pay for Some Security Improvements at Decker Towers

Apr 1, 2024 -

'Safe Haven': Vermont Is Considering Controversial Overdose-Prevention Sites. 'Seven Days' Went to New York City to See One.

Mar 20, 2024 - More »

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.