Published October 28, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 29, 2015 at 9:58 a.m.

When light hits the eye, the cornea refracts it. The iris regulates the size of the pupil, and the lens focuses the light further. Photoreceptor cells in the retina convert the light into electric signals, which are transmitted to the brain through the optic nerve, a bundle of approximately one million fibers. Most of the time, we just call this seeing.

For humans, sight is both a simple biological process and a neurocognitive puzzle. It's a gateway to big questions about self and truth that were first magnified by the invention of photography, followed by the moving image and now by the internet. "Fractured / works on Paper," the current exhibition at Stowe's Helen Day Art Center, bravely attempts to chart this nebulous territory with, as its title suggests, great specificity in material.

Curator Rachel Moore uses the work of 11 artists, two of them based in Vermont, to "illuminate physical quandaries of light, space/structure, and narrative in a formally impressive manner," as she puts it. The exhibition is impressive in both quantity and quality — it includes very large-scale works by artists Dawn Clements and Jane South (who have both, Moore notes, lectured at Johnson's Vermont Studio Center), as well as pieces from internationally known artists Leonardo Drew, Olafur Eliasson and Kiki Smith.

But "Fractured" is not just a vehicle for bringing art-world stars to a small-town gallery — Moore's vision is more egalitarian. She notes that the exhibit "is a showcase of some of the best artists in the world combined with emerging artists that applied through our submissions process." She also points out that the show's gender ratio — eight women and three men — is intentional.

Entering the Helen Day's second-floor gallery, the viewer is greeted assertively by South's "Excerpt," a freestanding sculptural installation resembling a camera, or a television, that has spontaneously exploded. South manages to evoke both devices because the structure's components are invented, mimicking media technology and its packaging but not replicating it. The entire piece is made from meticulously hand-cut and folded black paper arranged around a wooden structure, with a few wires and bulbs thrown in for good measure. Not insignificantly, the bulbs look a lot like the memory orbs in Disney Pixar's recently released Inside Out — small, glowing spheres, that each play an individual memory like a looping YouTube video.

South's work dominates the show, with three more of her sculptures in various sizes spread throughout the gallery. "Untitled (NC Yellow)" and "Untitled (Irregular Ellipse)" are similar to "Excerpt" in their resemblance to mutant Rube Goldberg machines. But they are nowhere near as chaotic; these smaller, wall-hung pieces are tightly assembled and look quite functional, though their function is unclear.

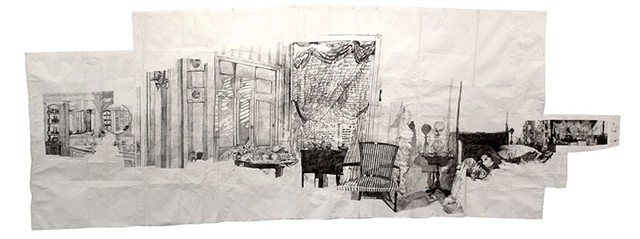

If South's sculptures are like imaginary ocular machinery, Dawn Clements' sprawling scenes suggest the product of a human recording device. The drawings "Mrs. Jessica Drummond's (My Reputation, 1946)" and "Lina's (L'angelo bianco, 1955)" each take up an entire wall. Depicting scenes from old films, Clements sketches female protagonists' domestic spaces in pen, frequently changing scale for a fragmented effect. The scenes are covered with mysterious handwritten notes (such as "instruct my sorrows"), time stamps and dates. By recording her thoughts and associations this way, Clements places herself into movies and worlds that were created decades ago. Her drawings are like sketchbooks from a journey where past and present meet, entangling her own life with cinematic fiction.

Olafur Eliasson's trio of color circles, made in 2008, as well as two pieces from Brooklyn-based Joan Grubin, directly reference the relationship of reflection, color and optics. Each of Eliasson's circles is constructed of three overlapping sheets of paper, presenting a spectrum of variation for each of the primary colors. They look like irises.

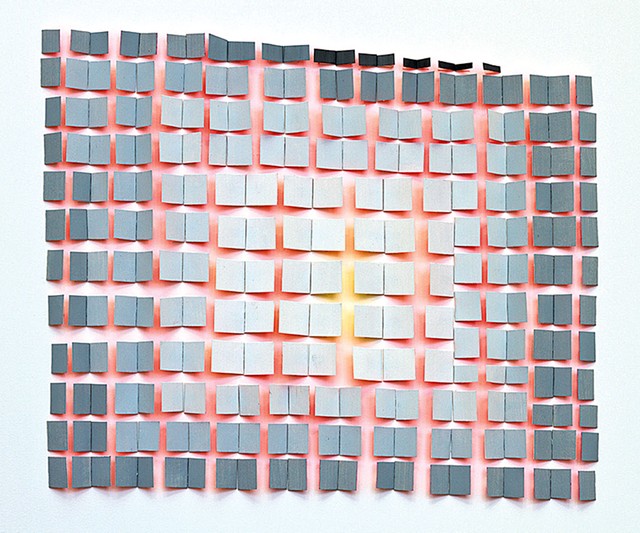

Grubin is more playful. Her "Pink Line Grid" is a blockish arrangement of small, rectangular pieces of black and gray paper partially affixed to the wall, like a grid of sticky notes. The space between the papers is pinkish, but the wall hasn't been painted — it's merely the canvas for color reflected from the underside of the black and gray squares. It looks like pure magic.

Vermont artist Peter Fried's painting "Grid #1" is like an inverse to Eliasson and Grubin: a decidedly lo-fi graphite and acrylic work of gray and black straight lines crossing perpendicularly, like an Excel spreadsheet painstakingly made by hand.

The theme of multiplicity continues in the work of Beka Goedde, Sarah Amos and Kiki Smith. Brooklyn-based Goedde's "Chord" looks like a life-size braided rug constructed of herringbone-patterned gouache and watercolor on paper, chopped up and layered for a slightly dizzying effect. Her collage "Three Chairs in Waves" presents a similarly constructed scene in which three chairs, as well as eating utensils, float in what appears to be a pleasant but zero-gravity kitchen.

Australian-born, now Vermont-based printmaker Amos also uses collage, but her "Blackbox Gum 2" is a collagraph — a type of print made from layering materials on a printing plate instead of directly onto the work.

Smith's "Evidence No. 1" employs a form of printmaking called cliché verre. The image is sketched onto a plate and then transferred to another surface. Here, two pairs of hands, or perhaps one pair drawn in motion, play a game of cat's cradle. The artist has added her fingerprints in white over just one set of the hands.

Other works in "Fractured" include sculptures from Leonardo Drew, Etty Yaniv and Kazue Taguchi. Drew's "Number 134D" and Yaniv's "At that moment, all spaces change" are both highly textural wall-mounted assemblages that evoke the ever-fluctuating balance of chaos and order and seem to deviate somewhat from the show's focus on light and narrative. And it could be easy to miss Taguchi's "Ilhabela," tucked into a corner space isolated from the rest of the gallery. The installation has floor spotlights pointed at Mylar and cellophane paper chains to create twirling, broken circles on the ceiling and walls.

"Fractured" is exciting because it engages with the discrepancies between physical sight and lived experience, while rebuffing the notion that high-concept shows should be high-tech or disorienting. Moore has assembled a remarkable diversity of works that deftly question how we see. In a time when we hear much discussion about what the internet is doing to our brains, "Fractured" is a reminder that fragmentation has been around for a long time, and that going back to basics can be revelatory. In art, after all, what's more basic than using paper to show what we see?

The original print version of this article was headlined "Seeing the Light"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Printed Matters: A Vermont Studio Center Collection Is on View and at Auction

Apr 24, 2024 -

Last Quarter: Spring 2024 Vermont Housing News

Apr 16, 2024 -

New Owners of Robert Paul Galleries Look to the Future

Mar 6, 2024 -

Sculptor Clark Derbes Gives New Life to Fallen Wood

Jan 10, 2024 -

Stowe’s Cork Restaurant Pleases With Wine and Italian-Inspired Comfort Food

Jan 9, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.