Published June 24, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated June 24, 2015 at 2:18 p.m.

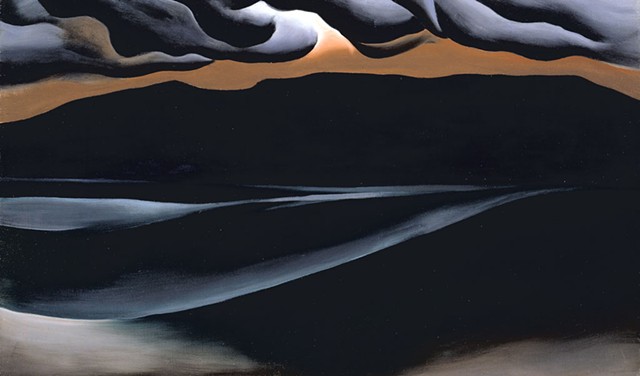

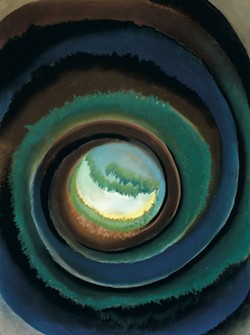

As beautiful as Lake George is, Georgia O'Keeffe made it even more striking in her many paintings of the mountain-rimmed, blue-green waters. She painted that New York landscape in starlight, in orange and yellow autumnal hues, in velvety layers of blue on blue. In all, O'Keeffe completed some 225 paintings of the resort area from 1918 to 1934. During those years, she spent part of every summer, and sometimes fall, in this town at the southern tip of the Adirondack Park, 35 miles from the Vermont border.

O'Keeffe continued to visit the lake until 1946, yet her connection to the region is virtually a footnote to her famous biography in the public's mind.

One of the most notable American artists of the 20th century, O'Keeffe is best known for her association with a very different place: New Mexico, the land of bleached cow skulls and desert flowers. That's where she based her life and her art from the 1930s until her death in 1986 at the age of 98.

Still, art historians agree that O'Keeffe's time in Lake George also played a significant role in her development as an artist. There she painted poppies, canna lilies and petunias in early examples of the enlarged flower paintings for which she would become famous. Long walks and still moments in the orchards, meadows and gardens on the Lake George property where she lived honed her sensitivities to the natural world.

"It really provided her with a visual foundation for her later career," explains Erin B. Coe, director of the Hyde Collection in nearby Glens Falls and cocurator of the critically acclaimed 2013 exhibit "Modern Nature: Georgia O'Keeffe and Lake George."

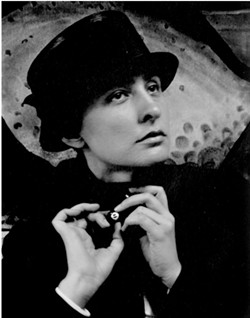

The region was even more important to another major art figure of the 20th century: O'Keeffe's husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who summered on Lake George for most of his life, and whose ashes remain there. He took most of his famous portraits of O'Keeffe — with her long, slender fingers; ink-dark eyes; womanly body and almost mannish face — in New York City, where they spent the winter. But the series includes some portraits from their time in Lake George.

Despite all that history, today it's hard to find any signs of O'Keeffe, or of Stieglitz, in this tourist haven that's chockablock with motels, mini-golf and water slides. The local historical society has a small display about the couple at the old red brick courthouse in the center of town. But the organization's office is closed, possibly to reopen in July, according to a sign on the dusty door.

One mile north of Lake George Village on Route 9N, a small historical marker stands on a clump of grass near the hillside property where O'Keeffe and Stieglitz lived. The sign was erected in 2012 by local art lovers and Coe, who spent five years researching O'Keeffe's presence in Lake George.

The hilltop farmhouse where the artistic couple summered, in the company of members of Stieglitz's family, is gone. So are the outbuildings — the "shanty" where O'Keeffe painted, the barns she depicted, the darkroom where Stieglitz printed his photos, the poplars and oaks that appear in both their works. A developer purchased the 37-acre property in the late 1950s and had the structures burned in a practice fire drill, as Coe relates in an essay published in the "Modern Nature" catalog. He then built the hodgepodge of ranch homes that now occupy the property.

"Everything's gone. There's nothing left. It's a 1960s suburban subdivision," Coe says.

People still come looking for the Stieglitz farmhouse, only to be disappointed, says Jephson Hilary, an art and antiques lover who lives with his wife, Barbara, in one of the few older homes remaining on the hill. The Hilarys operated an inn at the foot of the property for almost two decades and sold it last year. They, like the current owners of the Inn on the Hill, promoted the O'Keeffe connection and often encountered visitors who wanted to see the white clapboard farm where the artist lived.

"They do these pilgrimages and come looking for the house. And that's the sad thing, because it ain't here," Hilary says.

A British expat whose well-appointed living room speaks to a love of old things, Hilary supposes that back when the hill was scraped of the old farm buildings, a different mentality was in place. "There was no saving of anything. This was the '50s," he laments. "We wanted to flatten everything."

Why isn't there more local recognition of O'Keeffe and Stieglitz? "I don't know," Hilary says. The essential blotting out of the summer homestead of two famous 20th-century artists is "just a great shame," he notes.

O'Keeffe visited Lake George briefly in 1908 as a 21-year-old art student but didn't begin coming as a summer resident until 10 years later with the much older Stieglitz. At that time, he was her married lover and a New York City art-world insider helping to launch her career. The couple spent a few summers on the lakeshore at the formal Stieglitz family summer estate, Oaklawn. Stieglitz's father had purchased the Queen Anne-style mansion in 1886 and added the farm across the street to his holdings in 1891.

Oaklawn was sold in 1919, and that farm became the summer home for the family, including O'Keeffe and Stieglitz, who would marry in 1924.

The formal estate still stands as part of a condo time-share development. The exterior wears a modern skin — newish siding and roofing — that makes it difficult to discern the historic home underneath. A plaque at the front door notes its significance.

It was on the shoreline near Oaklawn that O'Keeffe scattered Stieglitz's ashes — at least some of them — in 1946. A few years later, in 1949, she made New Mexico her permanent home.

The changes to the places O'Keeffe inhabited at Lake George make it difficult to imagine her life there in the 1920s, but Coe offers a helpful description of the artist's routine in the museum catalog.

O'Keeffe walked into the village for her mail every day, passing the summer tourists, the souvenir hawkers and the high-speed trolley to Glens Falls. She sometimes hiked the two-mile trail to Prospect Mountain. She would have seen steamers coming and going along the 32-mile-long Lake George.

Especially in her later years, when O'Keeffe was focused on the spare, open landscapes of the Southwest, she described Lake George as almost oppressively green, and declared it not painting country. Although the Stieglitz family had a housekeeper, O'Keeffe expressed occasional frustration in letters to friends about the interruption of her creative work by household duties and obligations toward the extended Stieglitz clan at Lake George. She escaped much of that, and perhaps her husband's Svengali role, when she began spending time in New Mexico circa 1929.

In her younger days, though, when O'Keeffe was still in the throes of deep passion for Stieglitz, she sometimes raved about the beauty of the Lake George landscape in her correspondence with artist and writer friends.

The place certainly made an impression. Aspects of O'Keeffe's lasting vision as an artist took root in Lake George, says Katherine Hoffman, professor and chair of the fine arts department at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, N.H., and the author of several books about O'Keeffe and Stieglitz.

"Some of her landscape sensibility and sense of the play of light and shadow and water and so on, I think that's reflected in her Lake George paintings," Hoffman says.

O'Keeffe repeatedly painted the fallen leaves, the poppies of early summer, the apples in the orchard and, especially, the view of the lake from the farmhouse on the hill that rose steeply from the water.

The view is one of the few ways fans of O'Keeffe can connect to the artist in today's Lake George. A short walk up Hill Drive brings a pedestrian to a perch with an overlook of the lake not unlike O'Keeffe's perspective 90 years ago.

"You look at essentially what is her view," Coe says. "That's unchanged."

Without the farmhouse property, it's difficult for the village of Lake George to create the sort of artist tourism that flourishes in New Mexico, Coe notes. There, visitors can go to the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, as well as to her home and ranch, which are almost undisturbed. "You know you are in O'Keeffe country," Coe says.

Another missing link in Lake George is actual work by O'Keeffe. No paintings exist in local museums such as the Hyde or the Chapman Historical Museum in Glens Falls, six miles from Lake George; or at the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake. Nor is one of these small institutions likely to acquire an O'Keeffe work, given their going rate, unless it's through a bequest. Last year, a white flower painting by O'Keeffe sold for $44.4 million at auction, a record at the time for a female artist.

For the O'Keeffe "Modern Nature" exhibit, Coe borrowed some 60 works from museums and collectors, a mammoth task and a triumph of perseverance. The exhibit traveled to Santa Fe and San Francisco, attracting many visitors and raising the profile of the artist's connection to Lake George. But now the O'Keeffe paintings of the lake, the barns and the poppies have gone back to their owners.

Stieglitz gave photos to the family's beloved housekeeper, Margaret Prosser, and some of those remain in the region — one owned by the Hyde. Both the housekeeper and O'Keeffe sometimes rescued Stieglitz's prints from the trash bin after he discarded them because they didn't meet his standards, according to Coe.

While more Stieglitz photos could reside in attics or chests in Lake George, that's unlikely, given his renown. It's even less likely that someone might discover a lost O'Keeffe painting lying about. Not only has the artist grown more famous over time, but she worked primarily in oil and hence produced art in much less volume than her husband.

Hilary has found nothing in the nooks and crannies of his own house. "Believe me, I've looked," he says. He agrees with Coe that O'Keeffe paintings probably won't materialize in a dusty Lake George shed or basement any time soon: "I would think probably anybody who's got half a brain would have cashed in on it long since."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Georgia in New York"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

'Art/Text/Context' at the Fleming Museum Encourages Critical Thinking

Mar 8, 2023 -

Creating Abstract Art Inspired by Nature

Apr 6, 2021 -

Peak Parking: Crowded Lots and Trails Prompt Restrictions Along Route 73

Jul 24, 2019 -

Timber? Court Bars Tree Cutting for Snowmobile Trail in 'Forever Wild' Adirondack Park

Jul 24, 2019 -

Hiker Adam Valastro Aims to Break 46er Speed Record

Jul 24, 2019 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.