Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Public Libraries Adapt to the 21st Century … and Uphold Democracy

Published February 19, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated May 3, 2022 at 2:27 p.m.

Outside, frigid temperatures had turned Burlington's latest snowfall into crusty meringue and rocks of ice. Inside the more hospitable Fletcher Free Library on a weekday morning, it was business as usual. A dozen or so patrons staked out chairs or tables in the spacious atrium; others browsed the stacks, settled into private nooks or waited in the checkout line. Senior citizens studied newspapers, future chiropractic patients slumped over their smartphones, and industrious individuals clacked away at the library's computers. By the front desk, a staffer and an aggravated gentleman engaged in some kind of détente.

Though these murmured conversations, rustling pages and clicking of digital devices did not exactly equal silence, every patron on all three floors of the Fletcher Free was in shush mode, as if a librarian with finger to lips stood before them. As if this place were considered sacred. Yet when a gaggle of children burst through the front door with unrestrained outdoor voices, no one looked up. The bubble of excitement soon disappeared into a kids' yoga class.

Anyone who has ever entered a library is familiar with this scene — the self-enforced hush, the attitude of tolerance, the freedom of access. But if you haven't been to your public library in, oh, the past 10 or 20 years, you might be surprised by how things have changed.

From a largely expanded inventory of items on loan to community-minded programming and resources to librarians engaged in defending democracy's promise of equal access to information, "The public library is now in transition," said Vermont State Librarian Jason Broughton. Seven Days visited seven of them last week to find out how and why.

'Libraries Step Up'

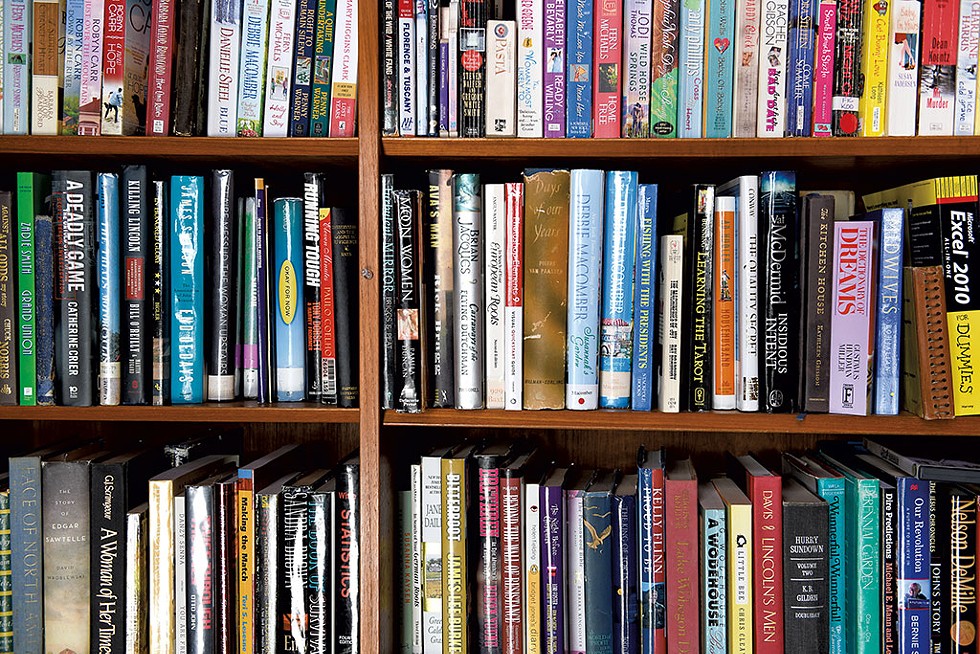

Today, at nearly every library, you can check out a motley assortment of things that aren't books — gardening tools, snowshoes, games and puzzles, telescopes, tennis racquets, bakeware — and, of course, "books" that are e- or audio. Two of the most popular items at the Fletcher Free, revealed director Mary Danko, are the ukuleles and the metal detectors. Its Library of Nontraditional Things even has a food dehydrator, a fold-up wagon and, um, human skull facsimiles. The Fletcher Free purchases items, Danko said, according to perceived or expressed community needs.

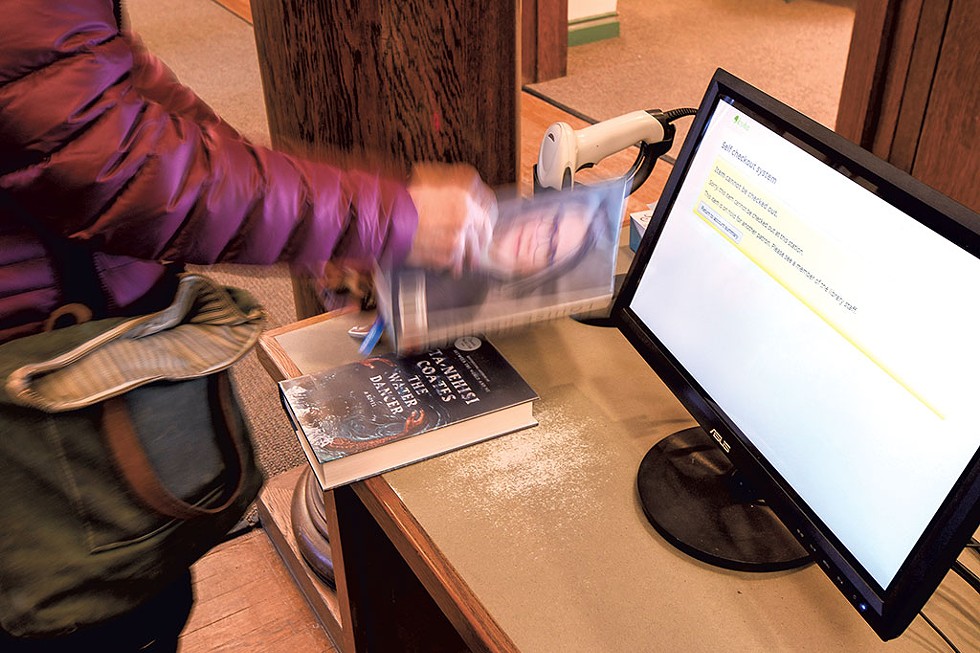

Another hallmark of today's libraries? Technology. With the incursion of the internet into modern life, the institution that passionately promotes free and accessible information for everyone has gamely taken on the responsibility of offering computer time to its patrons. It even teaches them, as needed, how to set up an email address or download a government form.

"You need technology to do anything," said Jessamyn West, "even apply for a job." West is a Randolph-based librarian, technologist and consultant who has been writing and speaking nationwide on the intersection of libraries, technology and politics since 2003. The creator of librarian.net and a former moderator on the group blog MetaFilter, she is something of a folk hero in library communities, not least for her work "on the front lines in battling the USA Patriot Act," as Wired put it.

One of West's frequent topics is bridging the digital divide — that is, how to provide internet access and training to people who lack it. In her talks, she notes that 10 percent of Vermonters — about 63,000 people — don't or can't use the internet. Thirty percent of those individuals report that broadband is not available where they live. Many of them are elderly, clinging to an analog world that no longer exists.

"If the government — town, state or federal — is requiring you to do a technologically mediated thing, they have a moral responsibility to help you do it," West declared. "Libraries step up because nobody else is doing it."

Even if they don't need help navigating their digital devices, patrons can go to libraries for the free Wi-Fi.

Another change — though it's not immediately obvious unless you peek at a library's monthly calendar — is the uptick in programming and community events. A sampling: language classes and voting information for New Americans. Chess clubs. Teen maker spaces. Banjo meetups. Racism discussions. Meditation instructions. Film screenings. Youth climate meetings. And that's to say nothing of a multitude of story times for children and families — including, in some Vermont libraries, a reading hour with drag queens.

Some contemporary library activities don't appear on any schedule. In more urban areas, for example, librarians have learned how to administer Narcan, should a visitor happen to overdose on the premises. Libraries are a refuge for homeless and mentally challenged individuals; many simply need a warm place to hang out, but some arrive with personal exigencies for which the holder of a library science degree is not trained. And yet library staffers have stepped up in this arena, too.

"One difference I've seen is how we have partnered with the Burlington Police Department and the Howard Center," said Danko, who has been with the Fletcher Free for three years. "I see my colleagues having to do social services."

Danko suggested that meeting these needs shouldn't be a library problem. "It's a community problem; it's the country's problem," she said. "We have to work on solutions to housing and services."

While waiting for that to happen, libraries continue to respond to their communities' needs as best they can.

"Historically, libraries were passive — a keeper of books, of knowledge," said State Librarian Broughton. "In contemporary times, they are community engaged and active in education."

Considerations of race, diversity, gender identity, disability, what it is to be a Vermonter — "all of that comes into play" in a library, Broughton pointed out.

Accordingly, he said, libraries today are more strategic in their offerings to the public — everything from health and fitness education to agricultural literacy. "It's really the library as an informational hub," he explained. "The library is part of the community ... and it's a safe place for discussion and civility."

#FundLibraries

The expanding provisions of libraries have not escaped the attention of Vermont legislators. A current Senate bill, S.281, would establish the Working Group on the Status of Libraries in Vermont. Its objective, over the next year or so, would be to study and report on the status of Vermont libraries — and, ultimately, to strengthen and support those libraries and improve their services.

Asked to comment on the bill's genesis, key sponsor Sen. Ruth Hardy (D-Addison) said, "I just really love libraries and think they don't get enough attention. They are often the hub of the community, especially in small towns."

Part of the reason for the proposed library study, Hardy added, "is to tell their stories and how they could do better."

One of those stories is about the challenges of the physical structures. Many of the state's libraries, built a century or more ago, have run out of space, need upkeep, aren't energy efficient and aren't as flexible as today's programming needs require, she observed. (Indeed, some tiny-town Vermont libraries still lack adequate plumbing or electricity.)

Hardy anticipates that other issues are library staffing and pay, as well as how libraries might be able to help in the face of, say, future climate crises or emergency management. "In some towns, residents rely on the library for information," she said. "How can we support their role in the 21st century?" The bill is currently with the Senate Committee on Appropriations.

Meantime, President Donald Trump's recently released fiscal year 2021 budget proposal, if approved, would permanently shutter the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services (along with the national endowments for arts and humanities), thus eliminating federal funding to America's libraries altogether. The IMLS gives grants to state library departments, funding that provides public libraries with crucial support services.

One vital service, noted Broughton, is administering interlibrary loans — a system that gives cardholders of even the smallest library access to millions of books housed elsewhere around the state and country.

U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) was among those who pushed back against Trump's proposal last week. "My life was influenced at an early age by getting my first library card at the age of four at the Kellogg-Hubbard Library in Montpelier," he wrote on Twitter. "From that moment forward I was a frequent visitor to the Children's Wing, cultivating a lifelong love of reading and learning."

The senator's tweet prompted thanks from some followers, accompanied by the hashtag #FundLibraries. But Leahy's support for the Kellogg-Hubbard has gone way beyond nostalgia and lip service. Famously a Batman fan with cameo roles in five films about the Caped Crusader, he has donated his cinematic royalties to the library — nearly $158,000 to date.

In addition, between 2000 and 2008, Leahy procured more than $1,323,000 in federal funding for his beloved Kellogg-Hubbard, according to a spokesperson at his office. In appreciation, the library named a new wing after the senator.

As for the president's proposal, it's particularly draconian but nothing new; conservative administrations have long tried to ax the arts and humanities. But with an acquiescent Republican majority in the Senate, will 2021 be the year they finally prevail?

There is reason to think not: The library community has managed to counter the past three budget-cut proposals, notes an article in Publishers Weekly. In fact, the IMLS has actually seen modest increases in budget allocation in each of the past three years.

In that article, American Library Association president Wanda Brown was quoted saying, "After three years of consistent pushback from library advocates and Congress itself, the administration still has not gotten the message: eliminating federal funding for libraries is to forego opportunities to serve veterans, upskill underemployed Americans, start and grow small businesses, teach our kids to read, and give greater access to people with print disabilities in our communities."

All this said, the fact remains that public libraries typically operate on a shoestring. Vermont is one of eight states that does not include direct funding for libraries in its budget, relying on the feds — and library "friends" groups — for support. Yet public libraries are being asked to do more, for all subsets of their communities.

A Portal and a Place

Vermont, a state with 251 towns, has 183 public libraries. That number does not include the dozens of school libraries, from elementary to college, across the state. Some libraries are municipal, meaning they are town or city departments, and the cost of running them is included in the town's budget. Some libraries are incorporated, essentially run as a nonprofit with a board of trustees.

We have Founding Father Benjamin Franklin to thank for establishing the first "membership library" in the colonies, in 1731. Years later, after the Revolutionary War, he also played a role in creating the first lending library — in the Massachusetts town that took his name. Public libraries began spreading in earnest after the American Civil War. The first totally tax-supported public library was built in Peterborough, N.H., in 1833, according to a history on the Digital Public Library of America.

Skip ahead a few decades, and U.S. towns that wanted to build their own libraries found a veritable patron saint in Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish American steel magnate turned philanthropist. "Building a Library outranks any other one thing that a community can do to benefit its people," he wrote in an 1889 magazine article titled "The Gospel of Wealth." "It is the never failing spring in the desert."

Carnegie spent close to $42 million to build 1,689 public libraries around the U.S. between 1881 and 1917. Four of the so-called "Carnegie libraries" are in Vermont: the Fletcher Free in Burlington (1904), the Fair Haven Free Library (1908), the Rockingham Free Public Library (1909) and the Morristown Centennial Library (1913). All still function as public libraries, and all have been annexed and renovated to create additional space for growing needs.

To that point, the Fletcher Free, which was renovated and expanded in 1981, has once again reached a condition that Danko called "at capacity." The library has just finished a feasibility study for funding another expansion. This time, though, the building would not be enlarged but "restructured" to make more efficient use of existing space. "People want more meeting rooms — we get more requests than we can handle," Danko said. "They want a café, a more cheerful children's area. They want better use of the outdoor space."

The city will be looking at the results of its study over the next six months, Danko said.

The need for more room is a common lament. "Our No. 1 challenge is facilities and space," said Dana Hart, director of the Ilsley Public Library in Middlebury. Built in 1924, the distinctive white stone building on Main Street seems large but apparently is not large enough. The basement community room is in constant demand.

One good thing about these growing pains? They illustrate how much town residents rely on and engage with their libraries.

Broughton has been the state's head librarian for two and a half years and reckons he's visited "over 100" of Vermont's 183 libraries to date. Not surprisingly, he's a major library enthusiast. For anyone else who might care to geek out over libraries, Broughton pointed out the most recent (FY2018) results of the Public Library Survey, available on the department's website. Created by IMLS, it's a compendium of information that the state's libraries are asked to update each year.

The survey report even handily offers a list of "superlatives," where you can learn such facts as "highest total circulation" (Fletcher Free, 389,347), "highest per capita collection expenditures" (Sherburne Memorial, $42) and "highest interlibrary loans sent" (Rutland Free, 5,581).

There is also a spreadsheet listing Vermont's libraries in alphabetical order, their town, population and other stats. What's perhaps most interesting are the metrics of "least" — for example, Hancock, population 300, is Vermont's smallest town to have its own library.

This terse compilation of statistics doesn't get into aesthetic, architectural or quirky features of Vermont libraries. It doesn't tell us, for example, that the Haskell Free Library & Opera House in Derby Line straddles the U.S./Canadian border, or that the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum houses a glorious art collection, or that the Groton Free Public Library offers free hot soup on Friday nights.

Rather, the survey is "a broad statistical summary of a year in the life of a public library," and its findings are essentially of use to government officials in "planning for the future and documenting the significance of libraries." Which is pretty much the goal of the Working Group on the Status of Libraries in the Vermont Senate.

Nearly every town wants to have a library, it seems, whether for the books or the communal opportunities or access to the world via broadband. "Pittsfield has had a volunteer-run library since 1901," noted West, referring to the Roger Clark Memorial Library. "Just last year, the town voted to pay a librarian."

The intrepid residents of West Danville reopened the Charles D. Brainerd Public Library in 2017 after years of inactivity. Housed in a former gas station, it claims to be the state's smallest library. Two other public libraries — in Danville and North Danville — are minutes away.

Regardless of size or circumstance, "a library is as much a portal as it is a place — it is a transit point, a passage." So wrote Susan Orlean in her 2018 nonfiction best seller The Library Book. It is a place where people can go not only to find books but, possibly, to find themselves.

If you're among the adults who recall, like Sen. Leahy, the magical hours spent in that portal as a kid, rest assured that today's children are doing the same — and borrowing Jenga games, Hula-Hoops and GoPro cameras, as well as books.

Who knows what Vermonters of the future will find there?

— P.P.

Light Reading

Worthen Library, 28 Community Lane, South Hero, 372-6209, southherolibrary.org

Keagan Calkins can't help but gush about the windows. "I remember the first time when it rained when we were in here in the summertime, I was like, 'Oh, something's happening outside, and I know about it!'" she said on a recent afternoon in the new Worthen Library building in South Hero.

When Calkins became the library director of what was then called the South Hero Community Library in 2015, it was tucked inside Folsom Elementary School, sharing the space with the school's own library, which lacked both windows and air conditioning. But in the summer of 2019, the library moved into a new, light-filled building just off Route 2. It is quickly becoming South Hero's premier community gathering space.

Sitting in cozy, low-slung chairs in front of one of those south-facing windows, Calkins and library board chair Ken Kowalewitz recalled the years of preparation it took to move into the 5,200-square-foot building.

Kowalewitz said the library board had been planning for this change since early 2013. After the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, schools across the country, including Folsom Elementary, stopped allowing most visitors during the school day. That meant community members couldn't access their library until after school hours.

The board felt a separate building was necessary, but it was mostly a dream until Ed Worthen, a retired professor and longtime library enthusiast, died in 2016 and bequeathed nearly $1 million to the library board. The new building cost $1.5 million in total.

The spot on Route 2, donated by developers Nate and Katherine Hayward and Matt Bartle, was also a major win for the library. Nearby is another new building containing a health center and a bagel shop, the town's firehouse, and an office building under construction. There are also plans for a senior center and a brewpub, and those involved hope to build a bustling commercial strip for South Hero.

Calkins called it a "librarian's dream" to design a new library from the ground up and said it was important to build a functional community space. There's a kids' section and story nook in the basement, so young visitors can make as much ruckus as they like without disturbing adult patrons. A large meeting space with an attached kitchen can accommodate everything from bridge groups and cooking classes to large meetings of the local historical society.

"We even debated about whether to call it a library," Calkins said. But in the end, she and Kowalewitz agree: A library is about much more than books.

— M.G.

Welcome Home

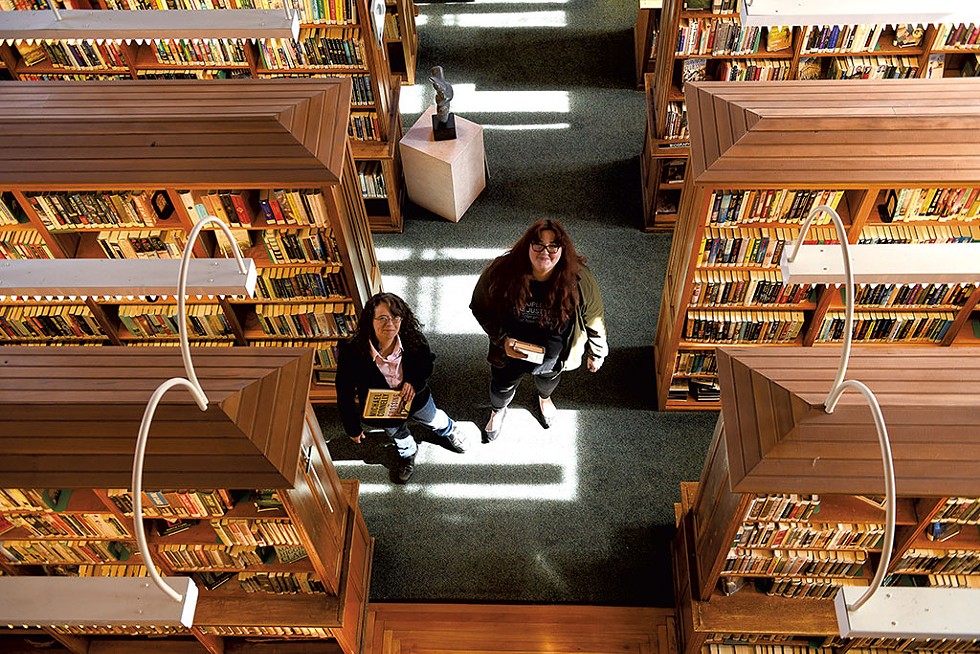

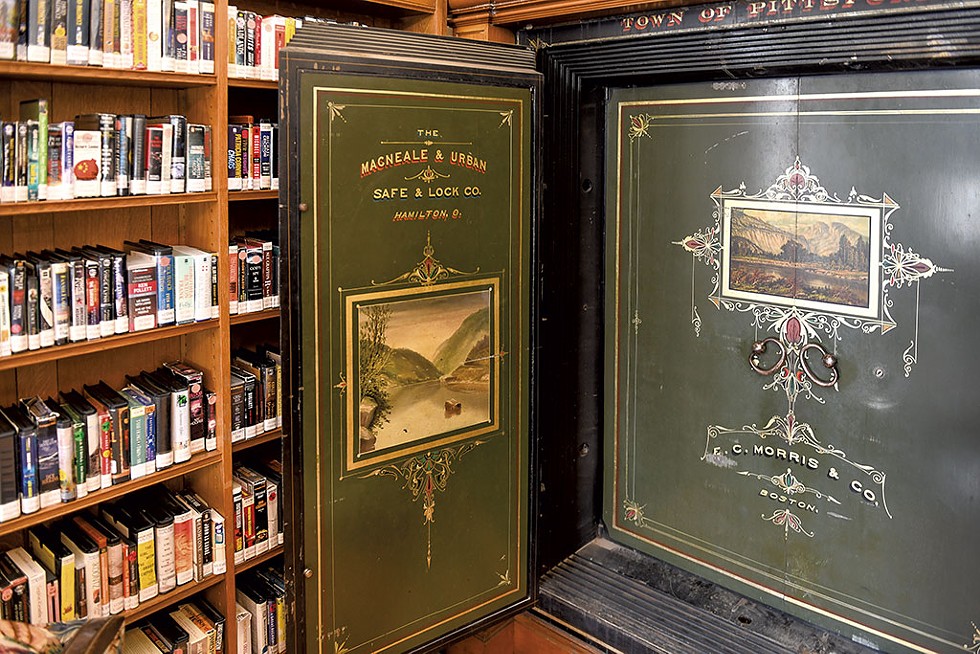

Maclure Library, 840 Arch St., Pittsford, 483-2972, maclurelibrary.org

Shelly Williams is not your stereotypical librarian. For one thing, she's way too loud. "It's usually other people shushing me," she said with a laugh. Her guffaw was loud enough to elicit a raised eyebrow from a young woman working the circulation desk of the Maclure Library in Pittsford as Williams chatted with Seven Days in the adjoining Vermont Room.

Williams, the Maclure's director, can't help herself. She gets excited talking about the library she's run for the last year and a half and worked for since 2012. That's especially true when you get her going about the red brick Romanesque building itself, which is among the more architecturally striking libraries in Vermont.

New York City doctor Henry Walker built the Maclure Library in 1895 to honor his deceased brother, Stephen. The siblings had summered in Pittsford and discovered the spring in Chittenden that supplies the town's water. Walker endowed the library with shares from the aqueduct company he subsequently founded.

The library is named for Scottish geologist William Maclure, who in the mid-1800s offered matching funds to library associations around the country, including $400 to Pittsford in 1839.

- Caleb Kenna

- Maclure Library

But the original community library association in Pittsford dates back even further, to 1796. It was a subscription library that operated on a rotating basis from residents' houses and was open only to men.

"Other libraries have claimed that because they were located in a building, they're older," said Williams. "But we really do have one of the oldest library associations in the state, for sure."

While the library no longer operates out of Pittsford homes — and now welcomes members of all gender identities — Williams and three part-time workers do maintain an inviting, homey feel at the stately Maclure. On weekday afternoons after school, two busloads of kids arrive at the library to study, do homework on computers, read or play games.

"It's a madhouse," Williams said fondly of the afterschool hours.

At quieter times, the library hosts everything from political discussions with state representatives to meditation classes to a meeting of pet fish enthusiasts.

"Dude, we are the Otter Valley fish club capital," said Williams.

In total, various groups utilize the library about 220 hours per month. That makes the Maclure's three floors something like a living room for the roughly 3,000 residents of Pittsford, 1,200 of whom are library members.

"It's more of a community center," said Williams, adding that the Maclure's collection is comparatively small — just 17,000 books.

Aside from upkeep on the ornate building, which is practically a full-time job on its own, Williams said her biggest challenge is maintaining that community feel.

"Simultaneously keeping 3,000 people happy is really hard," she admitted. It's also the most rewarding part of her job.

Recently, Williams took home, washed and folded the laundry of an elderly library member who was recovering from surgery. On another occasion, she made calls on behalf of a member who needed help finding a gardener. When she needs work done on the aging library, she'll look for laborers at the Pittsford Pub & Grill across the street.

"I never saw any of that in my job description," said the librarian. "But I love it."

— D.B.

On the Move

South Burlington Public Library, 155 Dorset St., University Mall, 846-4140, southburlingtonlibrary.org

click to enlarge

- Luke Awtry

- From left: Jennifer Murray, Kathryn Plageman, Verity Burnor and Jessica Joyal

Even with the long-awaited recent additions of H&M and, especially, Target, the University Mall in South Burlington can be a desolate place. With its closure this month, Sears was the latest casualty in a long line of mall tenants that have already shuttered or soon will.

It is oddly fitting, then, that the most vibrant storefront in the shopping center gives its wares away for free.

When the South Burlington Public Library opened at the U-Mall in November 2018 — ironically, just in time for the holiday shopping season — it earned a curious local distinction: It's the only Vermont library housed in a mall. Perhaps more importantly, it marked the first time the library had a home of its own.

Since it opened in 1971, the library had been located just down Dorset Street in South Burlington High School. According to Jennifer Murray, library director for the past six years, that location was problematic on a few fronts, including low visibility and accessibility.

"A lot of people just weren't comfortable going to the high school," she said, adding that certain individuals weren't even allowed on school grounds, for a variety of reasons.

Indeed, Murray said visits to the library have noticeably increased since it could claim Target and rue21 as neighbors. Currently, some 9,300 members borrow from 50,000 items in the library's collection, which now largely lives behind floor-to-ceiling glass walls offering a view of an IHOP.

DVDs, CDs and audiobooks make up about 10 percent of the total collection. The growing Library of Things features ukuleles, a bike helmet, blood-pressure monitors and a sewing machine, among other offerings. From the seed library, would-be gardeners can "borrow" seeds for everything from asparagus to zucchini. The computer lab is often full, occupied by students and seniors alike.

However, the move to the mall is only temporary, sort of a dress rehearsal for the opening of a new library on nearby Market Street in the summer of 2021. Murray said that space will be three times the size of its quarters in the mall. When completed, the new library will allow an expansion of programming, musical events and various community meetings, discussions and clubs.

The new building, part of the city's developing downtown center, will also present the library's eight full-time employees and numerous volunteers with challenges they didn't have in the high school. Recently, Murray's staff has undergone training on working with homeless populations. And a new first aid policy will cover the use of Narcan to treat potential overdoses.

That's all part of a larger vision of the new library as a community center built for the entire community.

"Libraries are full of potential, because the people who come in are full of potential," said Murray. "We are for everyone."

— D.B.

A Legacy of Generosity

Bixby Memorial Free Library, 258 Main St., Vergennes, 877-2211, bixbylibrary.org

Four Ionic columns and wide stairs in classic Greek revival style form the impressive and somewhat intimidating entrance to the Bixby Memorial Free Library. But inside, a large square foyer, lit from above by sunlight streaming through a colorful glass dome, seems to whisper, "Relax. You belong here. Stay a while."

Listed on the national and state historic registers, the Bixby was built in 1912 as both a library and a community center. It remains true to those functions today.

"It's so grand and beautiful, but you can walk in and have muddy boots and a tattered jacket and that's OK," said Maddy Willwerth, the library's interim director, public relations specialist and circulations coordinator. "And if you just want to come in and have a cup of coffee and you're not reading a book, that's OK, too."

A legacy of generosity pervades the Bixby's history. In 1907, Vergennes resident William Gove Bixby bequeathed most of his estate (composed primarily of wealth inherited from his sister) to the town for a library. Its unique design included not only rooms with book stacks but also three public restrooms for women (rare at the time) and multipurpose rooms for private gatherings.

"We are very lucky," Willwerth said, noting that most libraries have to build additions to house community gatherings. "Libraries that are just books nowadays don't survive. We have to be more than that." Last year, locals reserved the multipurpose rooms 360 times.

The Bixby serves the towns of Addison, Ferrisburgh, Panton, Vergennes and Waltham. Approximately 4,500 cardholders have access to a physical collection of 22,406 books, audiobooks, ebooks and more. The library also offers many recurring free events, including a weekly children's story hour, a monthly movie showing and numerous special functions, such as the recent Lego competition, which garnered 54 entries.

Willwerth normally works with three other staff, but as the board searches for a new director, she and two colleagues are holding down the fort with the help of volunteers. Ages 12 to 73, those volunteers contribute 43 percent of the total hours worked, Willwerth estimated.

"Our volunteers are the best. They are so kind and willing to go above and beyond to help people," she said. "They're so welcoming to anyone who comes in. And if they weren't, this place would feel entirely different."

— E.M.S.

Community Living Room

Kellogg-Hubbard Library, 135 Main St., Montpelier, 223-3338, kellogghubbard.org

Not a lot of shushing goes on at the Kellogg-Hubbard Library in Montpelier. When it happens, it's probably from a patron. "We are not likely to shush people," said Carolyn Brennan, the library's codirector. "We let people speak in here."

They also let people eat and drink in the library, as well as play hide-and-seek in their stocking feet in the stacks.

"Libraries are seeing a period of rapid change," said Brennan. "They are going from quiet spaces where people look for books to being a community living room."

That said, circulating books remains the No. 1 function of Kellogg-Hubbard: 280,627 books, DVDs, CDs and magazines were checked out of the library in FY2019. In that time, the library hosted 575 programs that drew 10,000 people to the institution, Brennan said. Upcoming programs include a Shakespeare camp where kids will perform Julius Caesar and the annual town-wide PoemCity. On a daily basis, the library hosts an informal, free afterschool program for 75 kids.

Kellogg-Hubbard was founded and built on Main Street in the mid-1890s. Outside its windows, the spires of neighboring churches pierce the sky. Inside, the spines of 64,279 books line the shelves. A nonprofit organization that serves six central Vermont towns, Kellogg-Hubbard operates on an annual budget of $929,100. Funding comes from a variety of sources, including allocations from member towns, income from a $4.5 million endowment, and fundraising of about $175,000 a year, Brennan said.

Among the library's 8,000 members is Sen. Patrick Leahy, who got his first card there at age 4 and keeps his current one on his desk in Middlesex. In a phone call from Washington, D.C., he shared the memory of walking to the library after school, a young boy who "took solace in reading." The children's librarian, Mrs. Holbrook, would greet him and talk with him about the books he was returning and new ones to check out.

The senator remembered a conversation from more than 70 years ago in which she asked him if he knew anything about Charles Dickens and gave him a copy of A Tale of Two Cities. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times..." Leahy recited.

"If children read, everything else follows," he said."I tell grade school students, 'You can be an astronaut, a firefighter, an architect, whatever you want to be. But learn to read first.'"

— S.P.

Plugged In

Whiting Free Library, 29 S. Main St., Facebook

About a year and a half ago, the Whiting Free Library was relocated to its current home on the second floor of the Whiting Town Hall. Overstuffed bookshelves are scattered around the spacious old room, which has wood paneling, high ceilings and a stage and is pleasantly musty. The move marked the dawn of a, well, bright new era for the small community library.

"It's the first time we've ever had electricity," said library trustee and Whiting native Tara Trudo.

The original Whiting Free Library — not to be confused with the Whiting Library in Chester — had been housed in an old Baptist church just a couple hundred yards north of the town hall on Route 30, aka Main Street. Built in 1843, the church became a library in 1929, when it was deeded to the town. The building fell into disuse for a period of years sometime before 1970, but it was reopened as a library again around 1973.

"It's a really cool building, but it's really falling down," Trudo said of the rustic old church. "It was beyond repair," she continued, citing rotting floorboards and windows that were "sliding off the walls."

The town hall, however, was in better shape. Except for occasional school plays, concerts and graduations, Trudo explained, it also had long been underutilized. Following the 2015 passage of Act 46, the Whiting Elementary School was consolidated; it was repurposed as a daycare, meaning the former school building got even less use. Add in certain modern-ish conveniences, and the move to town hall was a no-brainer.

"We're tackling the new century with electricity, heat, parking and bathrooms," said Trudo with a chuckle.

During the winter, the Whiting Free Library is only open on Saturday. That's actually an increase in operating hours, since the previous venue was only open in the summer. The library serves 60 or so regulars and about as many infrequent visitors, according to Trudo. It doesn't have official members and is open to nonresidents.

"Some of the other small towns around here don't have town libraries, so we like to be available to them, too," Trudo explained.

She has no idea how many books are in the library's modest collection and doubts whether any of the other four trustees would know, either. Additional offerings include a toy library, courtesy of the Brandon Area Toy Project, and several pairs of snowshoes.

With a population of about 400, Whiting is one of the five or six smallest towns in Vermont that maintains a library. The Whiting Free operates on a $1,000 municipal budget. Otherwise, it relies on donations and income from an annual book sale.

Still, according to Trudo, the library is a vital space in a town where the only other places you might bump into neighbors are the post office and a Congregational church.

"The store closed years ago," said Trudo. "Especially with the school being repurposed, we wanted to keep a sense of community here."

And they have. A Halloween party at the library last year drew more than 100 revelers. Other events, including snowshoeing, snowman-building parties and cabin fever nights, are popular, as well, especially with school-age kids.

Long-term, Trudo hopes to continue growing and improving the library, making it more accessible and welcoming, and perhaps even upgrading its catalog from the current card-and-stamp system to digital scanning. That last one might be a while, though.

"We may have gotten electricity," Trudo said, "but we still only have two plugs."

— D.B.

Ski Passes and 3D Printing

Ilsley Public Library, 75 Main St., Middlebury, 388-4095, ilsleypubliclibrary.org

The Ilsley Public Library was dedicated in 1924, the outcome of $50,000 that Col. Silas Ilsley and his widow collectively left in their wills to the town. But before the handsome white-stone building was erected, Middlebury had library associations. That is, groups dedicated to the sharing and discussion of reading material — a precursor to the modern book club. The first group, in 1848, was for men, who read the periodicals of the era. The Ladies Library Association established itself in 1866.

The ladies took informative minutes, many of which populate the line-item history provided on the Ilsley's extensive website. They allow a 21st-century observer to helicopter into yesteryear and find such developments as: "Six electric lights were installed" (1894), and "Ilsley staff are leaders in the Green Mountain Library Consortium that brings electronic services to libraries throughout the state" (2018).

But contemporary browsers are more likely to seek information on the latest free downloadable books from Project Gutenberg, or genealogy source material, or the time of the next story hour, "Engaging Racism" discussion or Vermont Humanities First Wednesdays lecture.

Director Dana Hart, who's been at the Ilsley for two years, is justifiably proud of the library's breadth of programming and patron resources. In a community of 8,496 — 8,921 if you include East Middlebury — the Ilsley has 4,502 registered cardholders, she said. Its 900 annual programs brought in 18,232 attendees, according to a 2019 impact statement. Hart estimated the library's current inventory at some 70,000 items, including print materials, ebooks, video and audio.

Most libraries now boast non-book items in their collections, but the Ilsley might be the only one to offer ski passes to the nearby Snow Bowl and Rikert Nordic Center. Patrons can also check out passes to the Makery at Middlebury's Patricia A. Hannaford Career Center — a membership-based collaborative that offers 3D printing and labs in engineering, building trades and sewing.

On a recent Saturday morning, the Ilsley hosted its first-ever free antique appraisal session with professionals Greg Hamilton and Brian Bittner. "We're trying to think outside the box," explained adult services and circulation librarian Renee Ursitti, who described her role as "day programming." It was the day after a major snowstorm, and attendance was modest in the community room. But Ursitti was pleased to see even the small trickle of folks who arrived with such items as a weathered duck decoy and old photographs.

"The community room is in use a lot," Ursitti said. "It's almost difficult for me to book [library] events in here, it's so busy."

Her observation echoed Hart's comment that the Ilsley "is really a community center" — a recurring theme among Vermont's libraries. And not evident at its capacious quarters — a large central reading room, a warren of meeting spaces, an adorable children's section, and stacks dotted with tables, chairs and computer stations — are the off-site locations of the Ilsley's outreach, including eldercare facilities and a teen center.

The physical facility, which expanded in 1977 and 1988, needs to grow again to keep up. "A 21st-century library needs to be flexible," Hart said. "We can only imagine how the library will change over the next century."

— P.P.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Check This Out | Public libraries adapt to the 21st century — with technology, tools and ukuleles — and uphold democracy"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Authors

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Margaret Grayson

Bio:

Margaret Grayson was a staff writer at Seven Days 2019-21. She now freelances for the paper, covering the art, books, memes and weird hobbies of Vermonters. In her spare time she dabbles as a pottery student, country music radio DJ and enthusiastic roaster of root vegetables.

Margaret Grayson was a staff writer at Seven Days 2019-21. She now freelances for the paper, covering the art, books, memes and weird hobbies of Vermonters. In her spare time she dabbles as a pottery student, country music radio DJ and enthusiastic roaster of root vegetables.

Sally Pollak

Bio:

Sally Pollak is a staff writer at Seven Days. Her first newspaper job was compiling horse racing results at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Sally Pollak is a staff writer at Seven Days. Her first newspaper job was compiling horse racing results at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Pamela Polston

Bio:

Pamela Polston is a cofounder and the Art Editor of Seven Days. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Pamela Polston is a cofounder and the Art Editor of Seven Days. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Elizabeth M. Seyler

Bio:

Elizabeth M. Seyler was a coeditor for the arts and culture section at Seven Days 2021-2022 and assistant editor and proofreader 2017-2021. She's a freelancer writer and editor who holds a PhD in dance and teaches Argentine tango.

Elizabeth M. Seyler was a coeditor for the arts and culture section at Seven Days 2021-2022 and assistant editor and proofreader 2017-2021. She's a freelancer writer and editor who holds a PhD in dance and teaches Argentine tango.

Latest in Culture

Related Locations

-

Bixby Memorial Library

- 258 Main St., Vergennes Middlebury Area VT 05491

- 44.16753;-73.25361

-

802-877-2211

802-877-2211

- www.bixbylibrary.org

-

Fletcher Free Library

- 235 College St., Burlington Burlington VT 05401

- 44.47690;-73.21009

-

802-865-7211

802-865-7211

- www.fletcherfree.org…

-

Ilsley Public Library

- 75 Main St., Middlebury Middlebury Area VT 05753

- 44.01256;-73.16906

-

802-388-4095

802-388-4095

- www.ilsleypubliclibrary.org…

-

Kellogg-Hubbard Library

- 135 Main St., Montpelier Barre/Montpelier VT 05602

- 44.26108;-72.57366

-

802-223-3338

802-223-3338

- www.kellogghubbard.org…

-

Maclure Library

- 840 Arch St., Pittsford Rutland/Killington VT 05763

- 43.70628;-73.02693

-

802-483-2972

802-483-2972

-

Whiting Library

- 117 Main St., Chester Brattleboro/Okemo Valley VT 05143

- 43.26364;-72.59724

-

802-875-2277

802-875-2277

-

Worthen Library

- 28 Community Lane, South Hero Champlain Islands/Northwest VT 05486

- 44.64698;-73.29635

-

802-372-6209

802-372-6209

- southherolibrary.org

Related Stories

Speaking of...

-

Libraries Help Kids Read 1,000 Books Before Kindergarten

Jun 4, 2024 -

Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help

May 1, 2024 -

Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April

Apr 24, 2024 -

Video: Visiting the Kellogg-Hubbard Library’s PoemCity in Montpelier During the Month of April

Apr 18, 2024 -

Q&A: Exploring the Haskell Free Library & Opera House With Hannah Miller

Mar 13, 2024 - More »

find, follow, fan us: