Published February 20, 2002 at 4:00 a.m.

Dooryard Flower

Because you’re sick I want to bring you flowers,

flowers from the landscape that you love —

because it is your birthday and you’re sick

I want to bring outdoors inside,

the natural and wild, picked by my hand,

but nothing is blooming here but daffodils,

archipelagic in the short green

early grass, erupted

bulbs planted decades before we came,

the edge of where a garden once was kept

extended now in a string of islands I straddle

as in a fairy tale, harvesting,

not taking the single blossom from a clump

but thinning where they’re thickest, tall-stemmed

from the mother patch, dwarf to the west, most

fully opened, a loosened whorl,

one with a pale spider luffing her thread,

one with a slow beetle chewing the lip, a few

with what’s almost a lion’s face, a lion’s mane,

and because there is a shadow on your lungs, your liver,

and elsewhere, hidden,

some of those with delicate green

streaks in the clown’s ruff (corolla —

actually made from adapted leaves), and more

right this moment starting to unfold, I’ve gathered

my two fists full, I carry them like a bride,

I am bringing you the only glorious thing

in the yards and fields between my house and yours,

none of the tulips budded yet, the lilac

a sheaf of sticks, the apple trees

withheld, the birch unleaved —

it could still be winter here, were it not

for green dotted with gold, but you won’t wait

for dogtoothed violets, trillium under the pines,

and who could bear azaleas, dogwood, early profuse rose

of somewhere else when you’re assaulted here, early May,

not any calm narcissus, orange corona

on scalloped white, not even its slender stalk

in a fountain of leaves, no stiff cornets of the honest

jonquils, gendered parts upthrust in brass and cream:

just this common flash in anyone’s yard,

scrambled cluster of petals

crayon-yellow, as in a child’s drawing of the sun,

I’m bringing you a sun, a children’s choir, host

of transient voices, first bright

splash in the gray exhausted world, a feast

of the dooryard flower we call butter-and-egg.

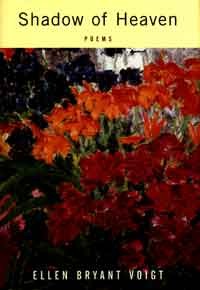

—from Shadow of Heaven, by Ellen Bryant Voigt

The book opens with a poem called “Largesse,” a lovely evocation of a windy market day after a night of rain in Aix-en-Provence.

…the olive trees gone silver,

inside out, and the slender cypresses,

like women in fringed shawls, hugging themselves…

stall after noisy stall, melons, olives,

more fresh herbs than I could name, tomatoes

still stitched to the cut vine, the soft

transparent squid shelved on ice.

Passing under a dead goose, however, the poem’s narrator has a startling vision of herself, blind, high on a ledge, and carrying a baby with “a spidery crack” in his skull. It’s a startling image, foreshadowing what I see as the principal theme of this collection — human mortality in an infinitely beautiful, yet profoundly imperfect, world.

“Winter Field,” which is also the title of the first sequence of poems in the book, moves from a frozen field “lost in snow” to a harrowing near-death experience of the narrator.

“We shouted, we shook you,” you tell me,

but there was no sound, no face, no fear, only

oblivion — why shouldn’t it be so?

For those hours

I was some other thing, and my body,

which you have long loved well,

did not love you.

“The Others” laments two miscarried children, “our lucky/or unlucky lost, of whom/we never speak.” With unsparing honesty, “Lesson” chronicles the dying days of a controlling, repressed mother who shows her daughter her mastectomy — “stitches/bristling where the breast/had been.” The poem concludes:

I did what I always did:

not weep — she never wept —

and made my face a kindly

white-washed wall, so she

could write, again, whatever

she wanted there.

In the last poem in the sequence, delightfully titled “High Winds Flare Up and the Old House Shudders,” death and thoughts of death are everywhere. A newly plowed field “looks like a grave.” A bee on the outside windowpane, working its mouth, is “my lost friend, of course, who lifelong/chewed his cuticles to the quick.”

And then we have a deceased friend known only as Jane, who, in an image as original as Emily Dickinson’s most riveting lines,

…calls from her closet of walnut and silk

for her widower to stroke her breasts, her feet,

although she has no breasts, she has no feet,

exacting pity in their big white bed.

The characters of Shadow of Heaven are surrounded by death. Yet every moment of their lives seems worth living as intensely as possible, perhaps because of their inevitable mortality. The dead themselves seem to agree, clamoring, as they do,

…more, more of this earth,

more of its flesh, more death, oh yes, and a few more

thousand last vast blue cloud- blemished skies.

Ellen Bryant Voigt’s own image-driven poetic intensity is increasingly rare in these days of mechanical “workshop” poetry and fiction. Every poem in the new collection, her sixth, comes straight from the heart. Yet Voigt writes with great technical mastery, and has one of the wittiest and most distinctive voices in contemporary American poetry.

“The Garden, Spring, the Hawk,” a sequence in 15 parts, is structured as a letter written from Baton Rouge to the narrator’s sister in Virginia. It’s exactly the kind of letter we’d all like to receive, full of sisterly conversation and marvelous feats of language — a male cardinal like “a struck match,” snakes asleep under a log a “cluster of commas,” Spanish moss “that lives on air, like gray Confederate ghosts.” Yet just beneath the surface lies some sad understanding between the sisters, more hinted at than spoken, of something “drained off, or worn away/and not yet, in its place, a new resolve.”

The third and fourth sequences, “The Art of Distance” and “Dooryard Flower,” contain the collection’s darkest and most powerful poems. They are loaded with memorable images and stories — Voigt is a terrific storyteller — such as an injured snake, shaken by a dog, “its blunt head raised/like a swimmer’s in distress”; a not quite dead turtle, being dissected for dinner by the narrator’s father; a dying doctor whose trained hands still automatically diagnose his own disintegration while he’s tied into a chair in a nursing home; and a farm woman whose two nephews come home from war with “four hands, three legs and half a brain” between them.

Shadow of Heaven takes its title from a passage in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, used as the book’s epigraph: “…though what if Earth/Be but the shadow of Heaven, and things therein/Each to other like, more than on Earth is thought?”

It’s an intriguing idea that’s probably crossed nearly everyone’s mind at one time or another. Leave it to Milton to put it into words. And what if he’s right? If he is, I for one hope that heaven too has hawks and turtles and dooryard flowers — and poems like the heartrending, gorgeous lyrics in Voigt’s latest collection.

Howard Frank Mosher is a Vermont novelist.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.