Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Seeing Is Believing: In 'The Undertow,' Journalist Jeff Sharlet Takes Readers Into the Trump Fever Swamps

Published June 7, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated June 14, 2023 at 10:00 a.m.

click to enlarge

- Alex Driehaus

- Jeff Sharlet in front of a mural by Mexican artist José Clemente Orozco titled "The Epic of American Civilization" in Baker-Berry Library at Dartmouth College

The idea — Sharlet's — was that I would sit in on the interview and perhaps learn something about him and his work. Then we would wander around Burlington and do one of his favorite things, which is to talk to strangers and take their pictures. The other idea — mine — was that Sharlet could do the interview in his car, which, I'm told by people who work in radio, can make a good sound booth in a pinch.

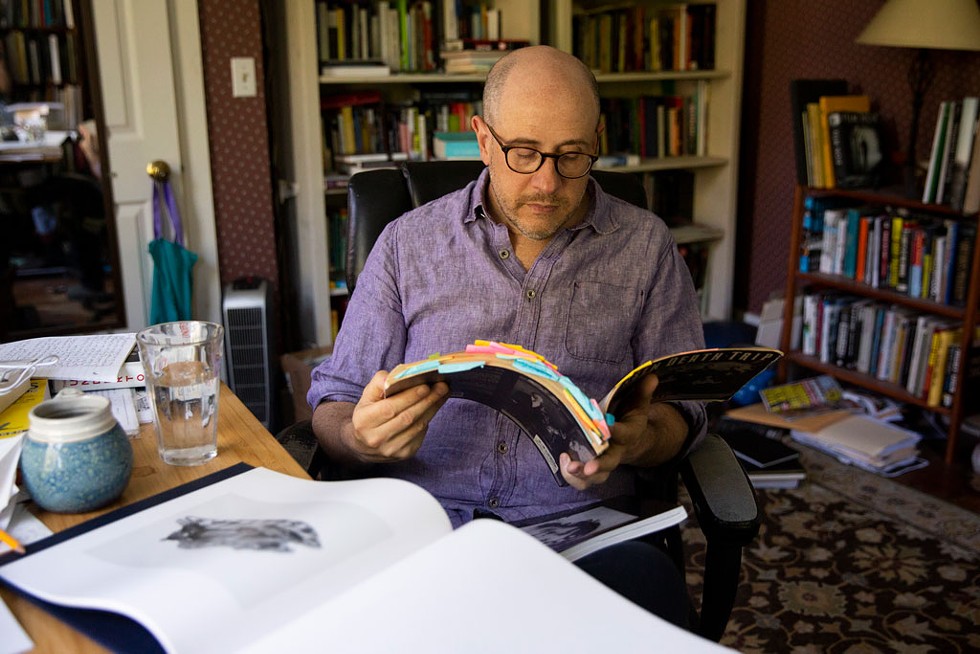

Sharlet logged on to Zoom from his MacBook, and his reflection stared back at him: a bald guy in his early fifties; salt-and-pepper stubble on his sideburns and his chin; horn-rimmed tortoiseshell glasses. Sharlet, who lives in Norwich with his wife and two kids, has been a professor of creative writing at Dartmouth College since 2010. He's been immersing himself in the world of the religious right, for magazines such as Harper's, GQ and Vanity Fair, for two decades, and he has covered Trumpism as a kind of death cult, an apocalyptic faith whose adherents believe themselves to be engaged in spiritual warfare.

Sharlet himself is a devout skeptic, the son of a Jewish father, a Soviet Union expert who taught at Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., and a Tennessee-born mother, who was raised Christian and embraced an evolving pantheon of deities and spiritual traditions. His desire to understand the outer edges of the human experience has led him into situations that most people with intact self-preservation instincts would endeavor to avoid.

Long before his work on Trumpworld, he spent a month at the northern Virginia compound of a secretive Christian nationalist group known as the Family, whose sphere of influence includes some of the most powerful people in the U.S. and foreign governments. That reporting led to his breakout 2008 book by the same name, which eventually became a Netflix documentary series and, Sharlet suspects, got him his teaching job at Dartmouth. He has traveled to Russia and Uganda to write about the brutal suppression of LGBTQ rights activists, for which he won a handful of national awards; he has hung out on Los Angeles' Skid Row to piece together the life of a homeless man from Cameroon named Charly Keunang, who was shot and killed by police.

This work has exacted a toll on Sharlet, in mind and body. In 2016, he was working at a frenetic pace, attending Trump rallies and watching the crowd rejoice at the future president's pantomimes of rape and violence. Then, that fall, at the age of 44, Sharlet had two heart attacks, or maybe it was one, drawn out over several days — the doctors weren't quite sure.

For a while, he told himself he was going to slow down and stop writing about terrible things. But by 2019, he was back at the Trump rallies, he said, "out of management of fear and anxiety." As QAnon and other conspiracy theories seeped into the lexicon of the right-wing establishment, the material, for Sharlet, had become irresistible. "For a person who has always been interested in magical thinking, there was some real rich magical thinking happening," he said. "On the one hand, I thought, I shouldn't go near that. On the other, I thought, Maybe it'll be good for me. It'll be invigorating." That tension simmers throughout The Undertow: how badly Sharlet can't look away.

His podcast interviewers, Khalil Gibran Muhammad and Ben Austen, appeared on the screen. "That's a man who's used to being on the road!" Austen said, taking in Sharlet's environs.

The word "mess" does not accurately describe the state of Sharlet's vehicle, which he didn't even use for most of the cross-country driving he did while reporting the stories in The Undertow. It would be more precise to say his car is a museum of dirt. On the passenger door: a faint ocher smear of a substance that had once been wet and, by the looks of it, chunky. In the cupholders and crevices of the upholstery: pre-dirt, crumbs, strands of hair and tiny pebbles. On top of the dashboard: dust on its way to becoming dirt, a film of fine particulate matter that, with time and moisture, had begun to acquire a stately permanence.

To minimize noise from outside, we kept the windows closed. Forty-five minutes into the interview, I could feel my pores opening in the humidity of Sharlet's aerosolized talking points. Around this time, the hosts asked Sharlet what he meant by "slow civil war."

"The slow civil war that I imagine — imagine," Sharlet caught himself, hearing the weakness of the word, "believe is happening right now — it's not coming. People say, 'Could there be violence?' and it always stuns me. What do you mean, could there be violence? There is already violence." At this point, the fan in Sharlet's MacBook sounded like it was running a marathon. "Now, what has been a simmer is coming to, perhaps, a slow boil. And maybe what it looks like is the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Or maybe what it looks like is what we're living through right now."

Sharlet was talking here about the steady drip of mass shootings, "every pregnant person who's dying for lack of reproductive rights right now," "the wave of queer and trans kids' suicides," all of which, Sharlet told his interviewers, should be viewed as fatalities of this slow civil war.

Since The Undertow's release in March, Sharlet has been making these arguments frequently, on TV and radio shows and in print. He is not a historian or political scientist, nor does he write like one. Sharlet considers himself first and foremost a storyteller, and his main interest in The Undertow is how the dream, or nightmare, logic of Trump works upon individual people, warping their sense of reality until they come to see themselves as combatants in a fight they believe is inevitable, is upon them already.

"When I asked, civil war, when the believers answered, civil war, we were speaking in metaphors we could barely comprehend," Sharlet writes. "We were describing a feeling that frightened or exhilarated us: a body coming apart."

Sharlet's need to understand the fracturing of the American body politic, he said, no longer has anything to do with personal ambition. When he talks to journalists about why he wrote The Undertow, he often talks about his oldest child, who is queer and nonbinary and struggling to cope with the daily violence against transgender people, with the fact that so far in 2023, 45 states have introduced or passed anti-trans legislation. In Sharlet's school district, which serves Norwich and Hanover, N.H., a group of parents has been trying to repeal a policy that protects the privacy of transgender students. The parents aren't fringe right-wing activists, Sharlet said. At least one of them went to Dartmouth, and their lawyer is the legal counsel for the New Hampshire state Senate.

So Sharlet drives around with a bottle of aspirin in his cupholder, trying to figure out what the hell is going on. "I'm too anxious to do anything else," he told me. "This is what I can do, and it's nowhere near enough."

Nothing to Fear

The Undertow is not the first book to detail the horrors of "the Trumpocene," a phrase coined by Sharlet's Dartmouth colleague, documentary filmmaker Jeffrey Ruoff, but it might be the first to do so with literary ambitions. Most of The Undertow's reviews have been positive, even reverent: the Washington Post called it "journalism-as-art"; the New York Times declared it "a riveting, vividly detailed collage of political and moral derangement in America, one that horrifyingly corresponds to liberals' worst fears."

Only the Los Angeles Review of Books was dubious, accusing Sharlet of falling under the doomsday spell of the far right. "Projection is a powerful force; if not careful, Sharlet and others will metastasize an otherwise provincial development into an international global menace," read one particularly spicy passage from religion scholar L. Benjamin Rolsky. (After Rolsky tweeted his review, Sharlet promptly blocked him.)

The Undertow is not entirely grim: Sharlet begins with a chapter on the late singer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte, whose anger — this is, after all, a book about anger — fed his art and his political commitments. The final essay, still pugilistic in its title — "The Good Fight Is the One You Lose" — is a meditation on the life and resistance ballads of folk singer Lee Hays. In between, though, the anger Sharlet documents is the kind that devours as it claims to redeem.

He attends a rally in Sacramento, Calif., for Ashli Babbitt, the 35-year-old woman who was shot and killed by a U.S. Capitol police officer during the January 6, 2021, insurrection, and tells the story of how she went down the rabbit hole. He goes to a megachurch in Yuba City, Calif., where the pastor proclaims that Hillary Clinton has been executed and that Trump remains the current, and 19th, president, the other 26 all being "illegal presidents." At another megachurch in Omaha, Neb., an usher and an armed security guard catch Sharlet talking to people in the parking lot and tell him that he isn't allowed to conduct interviews on church grounds. When Sharlet protests that he only has a pencil, and the security guard has a gun, the usher leans in and asks him, "How do you know that I don't have a gun?"

Sharlet's writing sometimes takes on the hallucinogenic quality of his subjects' delusions. In a chapter on a men's rights conference at a VFW in St. Clair Shores, Mich., from a piece Sharlet reported for GQ in 2014, he writes: "We were high in the manosphere now, the great phallic oversoul, the red pills were working, the rape jokes no longer landing like bombshells, they were like the weather, ordinary as rain." Sharlet had been drinking mudslides in a hotel room with the men's rights activists, people — men, yes, but also some women — who believe that feminism has personally ruined their lives, because women don't want to sleep with them.

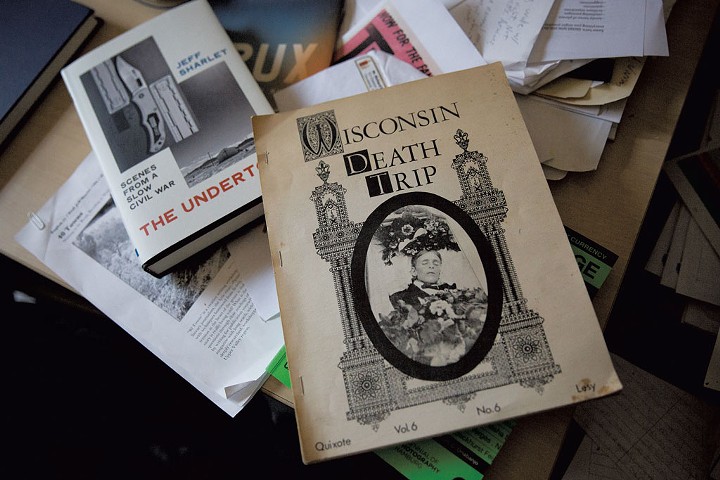

The GQ story infuriated the men's rights activists. After it ran, some of them called for retaliation against Sharlet and his family. Michael Lesy, Sharlet's thesis adviser at Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass., who has been a lifelong friend and mentor, told me: "He's often in the middle of people who would be described as extreme in their beliefs, but they see him not as something to be feared, but someone to be converted, and they're not frightened of him. And in the end, when he writes the story, they feel betrayed."

The men's rights activists sent him hate mail and death threats, accused him of being a pedophile and made memes of his face photoshopped onto the body of an extremely obese man, which they plastered all over the online manosphere. (Sharlet was heavier at the time, but not that heavy.) For a few weeks, Norwich police cased Sharlet's house in case anyone showed up to menace him. It's a fun story, how Sharlet finally got the harassment campaign to stop, but he won't tell it on the record for fear of pissing off the men's rights guys again.

Around this time, Sharlet said, he was slowly doing himself in. He slept about four hours a night and polished off whole bottles of Scotch while he worked. "I wasn't thinking, I should stop this," he said. "I was thinking, I'm going to burn myself up." Not long after he wrote about the incels, he went to Skid Row to report the Charly Keunang story. "I was very, very comfortable in that milieu," he said. Extremity has always been clarifying to him. Back then, he thought he could outrun, or outwrite, the reckoning with his own body. "The real danger is to make the mistake of absorbing all these stories as sequential, not cumulative," he said. His heart attacks would soon teach him that, but first, there was Trump.

Sharlet saw the way the media was covering Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, and he felt like everyone was getting it wrong.

"To say I felt an obligation is very pretentious. But the bar was so fucking low, because the press was so goddamn stupid," he told me. "They just sit there in their pen. And when the preachers preach at the rallies, they look at their phones." He wanted to write about the rise of Trump not as a political phenomenon but a religious one. His first magazine story on Trump, published in the New York Times Magazine in April 2016 and included in The Undertow, was titled: "Donald Trump, American Preacher."

Sharlet is sharply critical of the tendency among well-meaning liberals to "fact-check the myth," the notion that one can simply point out the errors in logic and blatant lies promulgated by Trump and his followers and thereby strip the myth of its power. Instead, Sharlet's approach is to try to enter the consciousness of the people who are under its sway, to understand their psychological investment in the promises of Trumpism.

Narratively and physically, Sharlet doesn't position himself above the fray when he is in the territory of the far right. He sweats and lurches with the rest of the crowd at Trump rallies, the better to see his followers' ecstasy. In these situations, Sharlet has the indisputable good fortune of being white, male and bald — nerdy enough to appear harmless, goonish enough to discourage people from trying to fuck with him. When he talks to people on the far right, he said, they tend to assume a kind of sympathy, even as he makes no secret of his disagreement with them. Right-wingers will open up to him, because they, too, see themselves as outsiders, as persecuted seekers of a higher truth.

"Jeff doesn't pretend to have opinions he doesn't have," said the writer Blair Braverman, a friend who accompanied him on several reporting trips for pieces that appear in The Undertow. "But he does it in such a way that people feel really seen, and they tell him all sorts of things that you wouldn't expect them to say. There's just something really disarming about him."

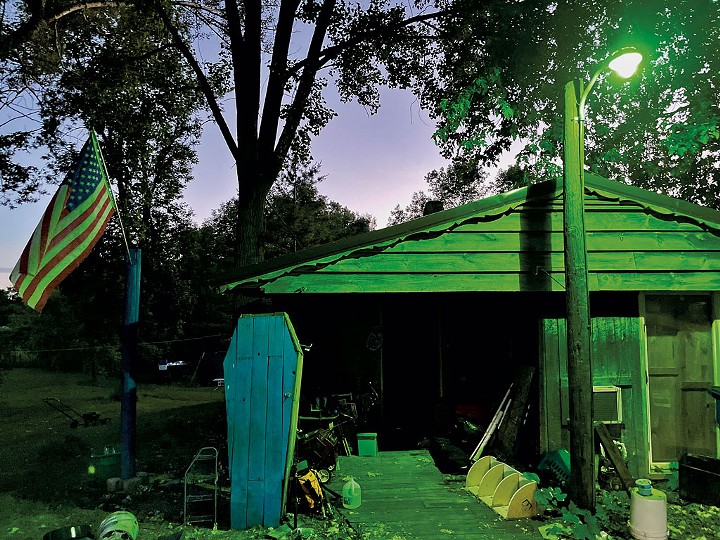

Roaming Charges

Sharlet's preferred journalistic method is talking to strangers. In The Undertow, he drives around and knocks on doors if he sees an interesting flag out front, which, to Sharlet, means anti-Biden, pro-Trump, pro-gun, pro-Nazi. In a chapter on Marinette, Wis., he goes up to a house with a "Fuck Trudeau" flag, and a guy named Rob Brumm invites Sharlet inside after determining that he is neither a Fed nor an intruder but "a fool." On a pool table in the living room is a massive pile of guns. In the midst of the guns — somehow even more unbelievable than the guns — is a cat.

Brumm, who claimed that he had participated in the January 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol and also that January 6 was a hoax, is Sharlet's ideal subject: someone who contains irreconcilable multitudes, whose sense of the world is shaped by an esoteric logic. Sharlet likes to read his subjects like tarot cards — they mean one thing if you look at them one way, something else if you look at them another — and there is nothing more occult than a chance encounter. So after we had hotboxed his podcast interview, we took a walk to find some strangers. Sharlet was vaguely on the hunt for material for future books, but future books were not the driving force of this expedition. Searching for material is his basic condition, of which books are sometimes a consequence.

As we approached Battery Park, Sharlet told me about a call he'd recently received at 11:45 one night from two students in his creative nonfiction class, who'd come to Burlington to do a story about heroin. They'd met a dealer who needed to get to Winooski, his students told him, and they wanted Sharlet's advice: Should they offer the guy a ride? "Thank God the call dropped just at that moment, so I didn't have to give an answer," Sharlet said. "Because the answer, of course, is 'Yes, you should totally go! But no, I didn't tell you to go!'"

Just then, a woman sitting on a bench in the park called us over. She wanted to know if we could help her use her "Obama phone" to call her a cab home, because she couldn't see the screen.

"Glaucoma, real bad," she explained. Later, Sharlet would tell me he'd learned what an "Obama phone" was while reporting on Skid Row: "The right had this big issue that Obama was giving out free phones to the homeless. And liberals were like, 'That's ridiculous. That's insane. That's not true!' And you get to Skid Row, and there's a big table where the government's giving out phones to the homeless. As they should!"

The Skid Row story ended up in This Brilliant Darkness: A Book of Strangers, which was published in February 2020. The book broke the format of Sharlet's previous works, combining narrative fragments with images he'd snapped with his iPhone during a period in which he'd lost faith in his work, the time after his father's 2014 heart attack and his own, two years later. After these intrusions of mortality, Sharlet began to suspect that the meaning he was searching for existed outside the precisely ordered world of the stories he told: "Plots that hurtled ever faster from beginning through middle to end — a brightly lit room in which all stories looked the same," he wrote.

So he turned to the dark. During his late-night drives between Vermont and Schenectady, where his father was recuperating, he stopped and talked to night bakers at Dunkin', road flaggers on the graveyard shift, guests at transient motels. Sometimes he took their pictures. These encounters became the stories in This Brilliant Darkness, a book that is as much about the people Sharlet met as his attempts to see them. His photos are deliberately amateurish, moments that Sharlet captured as they were already vanishing; the point is, Sharlet was there.

The woman in Battery Park, whose name turned out to be Shirley, handed me her Obama phone, and Sharlet looked up the number of a cab company. While I called, he took a photo of an empty can of Natty Daddy beer on the ground nearby. The cab transaction became more complicated: The dispatcher needed an actual address for the pickup, not just "Battery Park." Sharlet gave them the number of a duplex across the street, but Shirley, due to the glaucoma and, Sharlet speculated, what was in that Natty Daddy can, was not up to getting herself over there. So Sharlet offered her a hand and helped her off the bench, and I took the black tote Shirley had been carrying. "God musta sent you people," Shirley said, steadying herself on Sharlet's right arm.

This is a sentiment Sharlet has heard with perhaps uncommon frequency throughout his career. Most of his work, in one way or another, is about believers. In his early twenties, he and his friend Peter Manseau drove across the country to chronicle the varieties of religious experience in America, in ashrams and gas stations and bars where bras hang from the ceiling, and almost everywhere they went, people told them they'd been meant to come this way. In The Undertow, Sharlet shares what could only be described as a tender moment with a woman he calls Diane G. — she would only let him use her last initial, he writes, "for fear of Democratic retaliation" — outside a Trump rally in Sunrise, Fla.

Diane G., Sharlet writes, might be "closer to the new center of American life than you are." Sitting together in her white Cadillac SUV, Sharlet and Diane G. discuss her church, the church of Trump, in which Trump's seemingly random capitalizations in his tweets, his references to particular dates and numbers, are in fact an elaborate code meant for his followers. She tells Sharlet that the Clintons eat children. And then Diane G. tells Sharlet that her awakening to the true nature of the world coincided with a heart attack she'd had about a year earlier. Sharlet confides in her about his own damaged heart. Their meeting was no accident, Diane G. insists: "You were meant to run into me tonight."

So there we were with Shirley, who gripped our arms with astonishing strength as we helped her across the street and onto the nearest stoop. The cab, as it turned out, would not be coming after all, so Sharlet paid for an Uber instead. Shirley seemed to be in a cheerful mood now. While we waited for the Uber to arrive, Sharlet asked her how old she was; she would be 80, she told us, on May 29 — "a Taurus!" she crowed. (Actually, a Gemini, but whatever.) Sharlet told her that his birthday had been May 7, which also made him a Taurus. He told her that he and I were both journalists, working on a story together — were we? — and asked if he could take her photo. "Absolutely!" Shirley said. She beamed. "Cheeks up!" she told us. "Gotta keep your cheeks up."

The Uber arrived, and Sharlet helped Shirley inside. As the car drove away, I realized I was still holding her tote bag. Another mission! Sharlet was stoked. As we headed back to his car, he spotted a boy on a front porch, donning a fur hat and holding a Nerf gun. "Hey, little dude!" Sharlet said. "I'm a photographer. I love your hat and your gun. Can I take a picture of you with your gun and your hat?"

"Do you know what this hat is called?" the kid asked. We did not. The kid told us: "A ushanka." "Ah, the Russians!" Sharlet said brightly. The kid agreed to having his photo taken, but first he wanted to reload the ammunition in his Nerf gun. "All right," Sharlet said, taking the kid's photo, "you're ready to battle, man." After we'd gotten into Sharlet's car and started driving toward Shirley's apartment complex, Sharlet was still thinking about the ushanka boy. "That's one of my favorite types, the beefy kid with the high voice, who knows lots of information." Jeffrey Sharlet: former beefy kid full of information.

After we'd delivered the bag to Shirley's, Sharlet said: "This is why we're both crap journalists, but not total crap people — a good journalist would have gone through that bag."

It had never occurred to me to go through the bag. If Sharlet had left me with an open bag, would I be tempted to sneak a peek? Maybe, but only because I was writing about him, and then I would only open it ever so slightly, just to see what could be ascertained at a glance. No rummaging. I draw the line at rummaging. Shirley and her tote bag, on the other hand, never asked to be part of this story. "She's a bystander," I told Sharlet.

"Oh, no," Sharlet said. "She's a main character."

'Let's Go Look'

As we kept walking, I tried to ask Sharlet the kinds of questions that most journalists ask people they're profiling, such as: What was your childhood like? When did you realize that you wanted to do the thing you're doing with your life? He would start to give an answer, and then invariably he would become distracted — by Jehovah's Witnesses on Church Street; by a young person with hot pink eyebrows photographing dead lilacs on the ground; by a putty-colored wall, which, to Sharlet's mind, was no ordinary putty-colored wall, but a backdrop against which a subject might come to life.

Sharlet's longtime friend, the writer Quince Mountain, thinks this distractibility is a function of Sharlet's extreme openness to the world. "You can't walk down the street with him, because you'll lose him," Mountain told me. "He'll just start talking to Nazis or taking pictures."

As someone trying to obtain information from him, I found this tendency by turns irritating and endearing. "'You are as good as the last thing you wrote, and you are also not defined by that,'" Sharlet was telling me at one point, paraphrasing something Lesy, his college professor and mentor, had told him. "And I think that relieves me of that diva-ness — wow, letterpress printing? Let's go look."

We peered inside the darkened windows of Star Press on North Avenue. I saw a dim, cluttered room, but Sharlet, through his iPhone camera, saw something else. "That light becomes yellow," he said, pointing to a fluorescent fixture on the ceiling, "and then you get that blue stripe, the yellow stripe, this perspective, and that wire — that's pretty nice," he said. I had to agree. The wire was nice.

Sharlet's receptivity to the world — his desire to see the pain and the beauty in it — is also what makes him vulnerable. His next book is supposed to be about books that never got finished. But naturally, he doesn't want to finish that book. Instead he wants to do a book called Other People's Churches, an idea that came to him last summer when he was in Milwaukee, where his oldest kid was in a mental health treatment program. While he wandered around, he saw so many storefront churches, churches with boarded-up windows that stood only because it would be too expensive to bulldoze them.

"That's the undertow of The Undertow — this question of grief and mourning," he said, meaning his grief and mourning, over his kid and the state of the world. "I don't find my hope from light, airy places." We'd ended up at the Olde Northender Pub, where "Jeopardy!" was playing on the TV. The only question Sharlet answered correctly was about the 2019 mass shooting at a mosque in New Zealand. "On theme," he said. He's read the gunman's manifesto.

"People keep saying in the reviews that I have high blood pressure," Sharlet said. (By my count, only the New York Times mentioned high blood pressure.) "I do not have high blood pressure. I have the blood pressure of a lizard." Another thing he insists he is not: a "common grounder," someone who believes that if he only sat in a room long enough with, say, the Hanover parents who want to repeal the school district policy that protects trans kids, or with Diane G., the true believer in Sunrise, Fla., who thinks the Clintons eat children, they might discover some shared principle that zeroes out their differences.

Then what can be possible between two people? Sharlet answered this question, as he'd answered most questions, with a parable. He told me about The Boxer, a 1997 film starring Daniel Day-Lewis. ("I'm manly, giving a boxing metaphor, and I don't know anything about boxing.") There's a scene in the movie where Day-Lewis is in the ring with a Black man, Sharlet said, and instead of fighting for the entertainment of the spectators, the two men lean into one another, their bodies locked in a clutch.

"They just hold each other up," Sharlet said. "Like this." He wove his fingers together. "I cannot stand on my own."

"A fact of physics," I offered.

He smiled. "Wow," he said. "A fact of physics. That's it."

Then it was getting late, almost 9 p.m., so we parted ways. I went home, but Sharlet decided to wander around some more, even though he had a long drive home, to see what other words the night could give him.

Correction, June 10, 2023: A previous version of this story misstated the number of states that have successfully passed anti-trans legislation and the year Sharlet's book, The Family, was published.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

More By This Author

Latest in Culture

Speaking of...

-

Haley Scores Win Over Trump in Vermont

Mar 5, 2024 -

Nikki Haley Plans Campaign Stop in Vermont on March 3

Feb 26, 2024 -

Scott Calls on New Hampshire Primary Voters to 'Stop Trump'

Jan 19, 2024 -

Video: Following Seven Days' Paper Trail to Québec

Jun 21, 2023 -

Book Review: 'If It Sounds Like a Quack… A Journey to the Fringes of American Medicine,' Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling

Jun 14, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: