Published March 11, 2015 at 10:00 a.m.

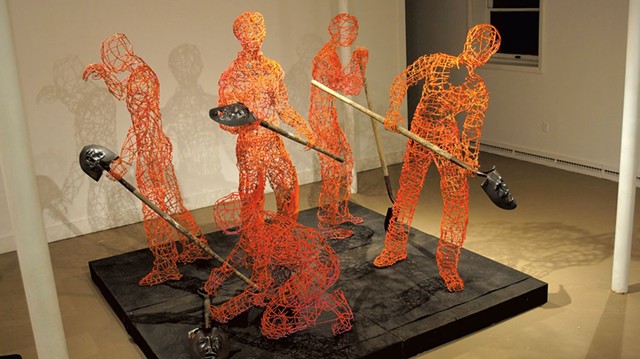

If Harlan Mack's art seems pretty, you're not looking closely enough. The painter and sculptor's intricate figures at his current Vermont Studio Center exhibit have gaping holes where their torsos should be, and they're painted a garish hunter orange. The welded-steel works cast eerie shadows onto the white wall behind them, adding an element of spectacle. What is most haunting, though, are the blackened steel faces welded into the shovels that each of Mack's figures holds. These faces seem to be grimacing in pain or anguish as the shovels are worked into the ground.

In the paintings that are also part of Mack's "Forecast/Revival" exhibition, mules, rabbits, dragonflies and human figures in mostly passive poses populate bleak landscapes. Domes are also scattered around these canvases; the artist explains that these are "rage tanks" that "collect negative emotions."

Mack, 34, grew up in rural Washington, Vt., in an off-the-grid house "way up in the middle of the woods, on a mountain," he says. In his VSC studio in Johnson, where he is working on sculptures, Mack shows a reporter the wooden trunk he built to hold dozens of paintings and drawings; each is part of the narrative behind "Forecast/Revival." Soft-spoken but talkative, he shares a few stories about his art.

Many of your works look like they're set in a nuclear meltdown, or some sort of worst-case climate-change scenario. How did you come to create "Forecast/Revival"?

All of this work is basically what produced this really long, complex, apocalyptic narrative. The stories I was making were seemingly random to me, and then I realized that I was working on this idea of a narrative, with folktale symbols. What bothered me was that all of these stories fit into a postapocalyptic narrative — I was resistant to the idea of a narrative for a long time. One day, I realized all of these little stories fit into the same world.

I saw this water tank that said "Glenn Mack water storage tank," and immediately saw within them the words "Mack Rage Tank." Then I came up with this idea of tanks that store unwanted emotions.

That's where the story gets way too big to tell it in any reasonable amount of time.

I have some time. Can you explain the core of the narrative?

Death is bored and wants to retire, so Death creates a clone of itself and then trains the clone without letting the clone know that there is more than one spirit of death. Death No. 1 needs to do these specific events in order to retire; the apocalypse is part of the scheme Death No. 1 creates. The rage tanks collect our negative emotions, and dragonflies eat those emotions. When rage tanks start to rupture, it seems like a catastrophe, and the dragonflies are free. [Humans] find a way to live among dragonflies. But because the dragonflies have been incarcerated in the rage tanks, when they're released, they have goldfish syndrome, and grow bigger and bigger outside of the rage tanks.

As they get bigger, we don't want them around us, and war breaks out. In the end, Death No. 1 has to convince the remaining humans to live on the backs of the four remaining dragonflies, which are the size of New York City. Death No. 1 set this up so that Death No. 2 would understand that respecting life is the most important part of death.

Many of your paintings have been in black and white on tarpaper, but some of your newer works are neon colored, though the settings look similar.

The bright colors are to trick people. I've heard people say after seeing them, "Oh, I want to live there," and I chuckle, because they really don't want to live there.

Your works include depictions of oil rigs, smoldering landscapes, workers with shovels and nuclear reactors, in addition to figures who are being attacked by other figures. What type of message are you trying to convey?

Everything racially is so shitty this year. Before, I was able to push things aside.

Is that because Vermont is so white, or that racism here is perhaps less visible?

It's not always the easiest thing to be a person of color where it's not very common. Growing up in a multiracial household, it was something we always talked about in my house. People call you mulatto; then one day in college I found out it means "mule." Drawing the mule became something about how people are identified without their consent, in the same way police [ascribe attributes to] people because of their professional opinion; then that opinion becomes law. Here in Vermont, I'm black, but put me in the city and I'm black to some and not black to others. I started making Eric Garner images around the same time I started making mule images.

Why do you depict Eric Garner in your art as wearing bunny slippers?

The night when the grand jury decision came back, I just stared at 10 blank pieces of paper — I couldn't paint. I wondered, would the police have killed him if he had on bunny slippers? Because wearing bunny slippers is something you do at home, where you feel comfortable.

Your figures with shovels, both in your sculptures and paintings, convey the sense that toil and oppression go across generations and landscapes.

There's the idea of the worker and labor, certainly. In the narrative, there are people out there who are determined to bury the rage tanks, or to uncover them. Burying a rage tank is like reverse warfare. Most people don't know they're there, but if I hid one around someone, it would eat their negative emotions and they would be a happier person. Digging the rage tanks up is a way to protect the tanks, because if they get overworked, they break, and then really large dragonflies are released into the world.

In this narrative, I'm the guy who invented the rage tanks. If I were in this story, I would totally dig them up.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Steel Forecast, Neon Revival"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Printed Matters: A Vermont Studio Center Collection Is on View and at Auction

Apr 24, 2024 -

Margaret Jacobs Creates Metalworks Inspired by Indigenous Culture

Nov 1, 2023 -

After the Flood, Vermont Studio Center Goes Back to the Drawing Board

Aug 16, 2023 -

At 'Exposed' in Stowe, Sculptors Consider the Future

Sep 28, 2022 -

The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, June 23 to 29

Jun 21, 2021 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.