Published December 17, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

So you've written a book. You've polished it within an inch of its life. Maybe you've already submitted it to every possible New York agent or publisher. Maybe your work has a local relevance that out-of-staters don't "get." Or maybe you simply prefer the idea of working with a Vermont-based company.

Whichever it is, once you start researching, you're sure to discover the proliferation of small local publishers. In the past few decades, new technology has made putting words on paper (or screens) easier and faster, leading to a steady uptick in the number of manuscripts seeking a home and publishers offering one.

But what exactly do they offer? For a writer shopping a manuscript, many caveats are in order. In April 2013, Peter Campbell-Copp of Manchester was sentenced to six months in jail for taking as much as $200,000 from authors whose books he'd promised to publish through his company Historical Pages. Most of those tomes never saw the light of day.

But for every scam artist, a new small publisher is struggling to survive the old-fashioned way — by making money flow to writers, not away from them. Unlike vanity or subsidy outfits, these publishers are selective and generally have a defined market niche. They seldom give writers advances, but they do offer royalty percentages unheard of in the Big Five.

The trick is selling enough copies to make those royalties count. While some literary genres sell like hotcakes online, shelf space in stores is still key to success in others. Any bookseller can order any book that has a distributor, but most will not stock a book unless the publisher permits the return of unsold copies.

Here at Seven Days, we receive dozens of books every year from local micropublishers. We chose three with growing lists and asked their owners a set of questions about how they approach their business. We left out larger local houses with long-established reputations, such as Chelsea Green Publishing. And we couldn't cover all of the interesting smaller presses, such as Ra Press or Verdant Books.

We hope this partial survey will be helpful to authors wondering what sorts of questions they should ask prospective publishers — and to writers and readers seeking inspiration. Because, if these three startup publishers share one thing, it's a steadfast idealism about the power of the written word.

Wind Ridge Books of Vermont

This fall, Wind Ridge Books took a road less traveled: It went nonprofit. What began as a division of Shelburne's Wind Ridge Publishing (producer of the Shelburne News and other papers) is now an independent "curatorial imprint" of Voices of Vermonters Publishing Group, which has a pending 501(c)(3) application.

"I think going to a literary and curatorial and nonprofit model is how to save the book-publishing industry," says Wind Ridge director and managing editor Lin Stone. "It's like the performing-arts model, where you link arms with the patrons to help make the art happen."

Wind Ridge will maintain its HQ at the cozy red Writers' Barn in Shelburne, where writers such as poet Daniel Lusk — president of the new nonprofit's board — teach workshops to the community. On a recent Friday morning, Stone's papillon, Hummy, greets a visitor to a room full of books.

When you talk with publishers, conversation inevitably turns at some point to Amazon.com. Soft-spoken with an English accent, Stone describes the megaretailer as a "commodities market, akin to orange cheese and cheap margarine."

Her mission? "We wanted to be the artisan cheese instead of the cheap commodities cheese," she says with a smile. "We wanted to curate good work."

To that end, Wind Ridge has launched a fundraising campaign from its website. "It feels a little bit like a small active resistance to go in this direction," says Emily Copeland, a Saint Michael's College prof who's vice president of Wind Ridge's board.

"And if you can't do this in Vermont, where can you do it?" Stone adds.

When did you found your company? 2009.

Why? "The book division came out of our newspaper columnists in the beginning, and then we reached out further to the Vermont Public Radio commentators," Stone says. "Then, of course, the manuscripts started coming in, and we began growing in new ways."

How many books have you published in total? 20.

How many this year? Six.

Some recent titles: Two books by Lusk: Girls I Never Married (memoir) and Kin (poetry). Handing Out Apples in Eden (poetry) by Malisa Garlieb. Please Do Not Remove: A Collection Celebrating Vermont Literature and Libraries, edited by Angela Palm.

Do you do offset printing, print on demand (POD) or both? Why? "I try to avoid offset printing for ecological as well as economical reasons," Stone says, though she still uses it for occasional art books. When publishers undertake print runs that don't sell well, she jokes, the books end up as "attic insulation."

What is your distribution? "We work with a vertically integrated printer and distributor [Lightning Source/Ingram]. So you can order a book in Australia; you can order a book in London. If you order it here, it'll come from Pennsylvania. Our books are all returnable."

What are some stores where readers might find your books? Phoenix Books, the Flying Pig Bookstore, other local independent bookshops and gift stores.

How do you find submissions? Some writers, such as poet Garlieb, connect with Wind Ridge through its workshops. Others submit from afar. But, as its name indicates, the publisher prefers to see work from Vermont writers. "Why go elsewhere when you've got so much talent locally?" asks Copeland, who heads the editorial review committee.

How many did you receive this year? 60 or 70.

Who edits your books? Copeland does the developmental editing. Lusk notes that his book had a thorough going-over by two editors.

What is your target market? "Serious readers. It's a literary market," Lusk says. Stone adds: "We're not trying to be elitist, but we are trying to be the best."

How do you reach it? What promotional tactics do you use? "We support authors by submitting their books to national competitions," Lusk says. "We support their readings with press releases. The book is not only well made, but nurtured into the marketplace."

How do you pay authors? On its original business model, WR gave 50 percent of profits to the writer and 10 percent to the writer's charity of choice. The shift to nonprofit status will change that. "Now we're the charity!" Lusk says.

Do authors ever pay you? WR offers paid publishing services to authors through a separate imprint called Red Barn Books. While writers who don't make the cut for WR publication are invited to sign up, Lusk says, "The press isn't making any money off them. It's a revenue stream that helps us to keep the designers at work."

What's a best seller for you? Brewing Change: Behind the Bean at Green Mountain Coffee Roasters by Rick Peyser and Bill Mares. It's been translated into Korean.

Future plans? Stone says WR is working on crafting alliances with the Vermont College of Fine Arts, refugee organizations and farmers. "We're always looking for ways to give voice to the underserved communities," she says. WR will continue to organize art exhibits in conjunction with poetry releases, as it did recently with Burlington City Arts.

Green Writers Press

Some literary folk shy away from discussing money. Not Dede Cummings, who founded Green Writers Press in West Brattleboro last year. "I paid out my first royalties," she says excitedly by phone. "We're going to start generating some income, probably next month." (The company is incorporated as an L3C, or "low-profit," which can receive certain grants unavailable to a regular LLC.)

As for the publisher and her only staffer, senior editor Robin MacArthur, "Neither of us is making any money yet," Cummings says. "She's got, like, three different jobs. So do I."

One of those jobs is writing. A Middlebury College grad with Boston publishing experience, Cummings has published wellness and gardening books with Skyhorse Publishing and Hatherleigh Press. She also "dabbles" in literary agenting, and designs many of her own press' books.

As its name indicates, GWP focuses on both sustainable practices and green topics. It can sell you an earnest anthology on climate crisis, a kids' book about a young eco-crusader, or a "cli-fi rom com" (that's "climate fiction"). Cummings says her goal is "to get out the word and build a lucrative business, but also spread a message of hope and renewal, and not a message of doom and gloom."

When did you found your company? 2013.

Why? "I was looking around for something to do," Cummings says. "Book design is slowing down. I woke up one morning and had this refrain going through my head, from Bill McKibben's The End of Nature: 'There's so little time.' We all know climate crisis is at hand. The thing I know how to do best is to make books. Let me use that knowledge to raise awareness, to entertain, to inform."

How many books have you published in total? 11; five more are slated for spring 2015.

How many this year? 10.

Some recent titles: Contemporary Vermont Fiction: An Anthology edited by MacArthur. Polly and the One and Only World, a young-adult novel by Vermont author Don Bredes. Winter Ready, poems by the Northeast Kingdom's Leland Kinsey.

Do you do offset printing, POD or both? Why? Cummings uses Vermont's Springfield Printing for hardcover books, color books and presales over 1,000 copies, she says. Other books are printed on demand by Lightning Source. All paper is Forest Stewardship Council-certified.

What is your distribution? Midpoint Trade Books. Cummings focuses on getting books into brick-and-mortar stores, she says. That can mean making direct connections, as when she walked into D.C.'s Politics and Prose Bookstore and asked to speak to the buyer. "Now they're carrying [our book]."

What are some stores where readers might find your books? Phoenix Books, Northshire Bookstore, Everyone's Books.

How do you find submissions? GWP is listed as a market in Poets & Writers but "not that aggressively acquiring."

How many did you receive this year? 200.

Who edits your books? "I'm more of a developmental editor. I'll do the first read; Robin will run the whole project."

What is your target market? "Place-based writing, environmental themes, nature or climate-change activism is the overarching theme of our acquisitions."

How do you reach it? Cummings says she focuses on word of mouth, social media presence and coaching authors on tactics. "I tell writers: The book is part of your whole brand."

How do you pay authors? GWP pays 25 percent of net profits to its distributor and splits the remaining 75 percent 50-50 with the author.

Do authors ever pay you? No.

What's a best seller for you? The Bodies of Mothers: A Beautiful Body Project is approaching sales of 4,000 copies, Cummings says. Contemporary Vermont Fiction sold out its first printing of 250 in less than a week; Bredes' novel is already in a third printing.

Future plans? Cummings says she'd like to collaborate with other Vermont publishers — while also looking beyond. "We want to be global. We have books that are being bid on for translation rights."

Fomite Press

Publishing is a labor of love for Burlington couple Marc Estrin and Donna Bister. When Cathy Resmer profiled them for Seven Days in 2011, she wrote that they "haven't turned a profit ... and they don't intend to."

Since then, their ideals haven't changed, but they've published a lot more books. Estrin, a prolific novelist whose own books are currently published by Brooklyn's Spuyten Duyvil, does the editing. Bister handles the production duties on top of her full-time day job.

Estrin first concocted the name "Fomite" for a fictitious publisher in one of his novels. "So the press started as a gag," he writes in an email, "went on to being an experiment and is now sailing along."

When did you found your company? Early 2011.

Why? "I [Marc] had been to enough open mics, and said to myself so many times, 'Someone should really publish that!' that one day I just said, 'Why don't Donna and I publish it?'" He also welcomed the chance to experiment with POD technology.

How many books have you published in total? 54.

How many this year? 18, with "another 12 in some stage of production."

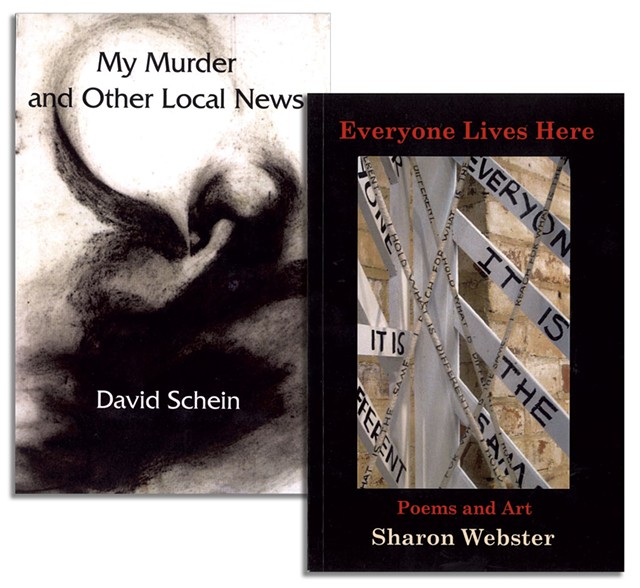

Some recent titles: The Return of Jason Green, a novel by Vermont Rep. Suzi Wizowaty. Everyone Lives Here, poems by Burlington's Sharon Webster. My Murder and Other Local News, long-form poems by Vermont actor David Schein.

Do you do offset print runs, POD or both? "We chose POD for many reasons — financial (low up-front costs, allowing us to give a larger share of royalties to authors); logistical (no need to maintain stock); and ecological."

What is your distribution? Fomite can't afford to make its books returnable, which "makes it tough for most stores to routinely stock Fomite titles," Estrin says. Stores and consumers can order the books through distributor Ingram.

What are some stores where readers might find your books? Crow Bookshop, Bear Pond Books.

How do you find submissions? "I am someone who hates saying no to anything," Estrin admits. He'd planned to stick to submissions from writers he knew and trusted. But then a listing for Fomite popped up on an online writer's resource, bringing a flood of unsolicited manuscripts. Soon "we had discovered really interesting manuscripts from as far away as Bulgaria."

How many did you receive this year? 25 or 30, plus requesteds.

Who edits your books? Estrin reads submissions, selects them and "work[s] on a manuscript word by word with an author."

What is your target market? "People who value literature and who are interested in reading things that push beyond commercial genres. We even have a category called 'Odd Birds: Eluding the Net of Classification.'"

How do you reach it? Fomite encourages its authors to cross-promote and keeps an eye out for contests they might enter. Marketing advice, a comprehensive website and "readings, events, social media" are also part of the package.

How do you pay authors? They get 80 percent of income generated by sales.

Do authors ever pay you? No.

What's a best seller for you? "We don't have best sellers. The books are out there as long as there is Western civilization, so who knows how many copies of a title will be sold by 2050?"

Future plans? Estrin would like to develop the press' "teaching component" and to publish more bilingual books. But mainly he just wants to keep Fomite going "as a postcapitalist operation. Our unstated motto is: 'Publishing does not have to be a business.'"

The original print version of this article was headlined "Of Royalties and Resistance"

More By This Author

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April

Apr 24, 2024 -

Video: Visiting the Kellogg-Hubbard Library’s PoemCity in Montpelier During the Month of April

Apr 18, 2024 -

Hancock's Whiskey Tit Press Publishes Books No One Else Will

Dec 20, 2023 -

The Latest Issue of '05401' Honors the Architects, Idols and Thinkers Who Shaped Its Eclectic Publisher

Nov 22, 2023 -

Washington Post: Vermont Has the Most Working Artists Per Capita

Aug 22, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.