Published May 13, 2009 at 5:10 a.m.

After six months of snow and sticks, the sight of a green field studded with dandelions is priceless. But you can’t actually make money growing the ubiquitous “weeds” — or can you?

Ask the owners of Montpelier’s Kismet, where patrons shell out $3.50 for a large “dandelion latte” made from the fuzzy flower’s roasted and steeped roots. The tan fluid may sound like a strange thing to swig, but fans go for its earthy, roasted flavors and hint of bitterness offset with maple syrup.

And, no, the restaurateurs aren’t sneaking around digging up lawns. They purchase organic dandelion root from Richard Wiswall and his wife, Sally Colman, who own Cate Farm in Plainfield, just 15 minutes down the road. Besides dandelions, Cate Farm proffers other crops you might find growing wild around your compost heap, such as burdock root and echinacea.

It may sound like niche production taken to an extreme, but the fact is, 52-year-old Wiswall has it down to a science. Years ago, the Middlebury grad determined that he could earn more growing dandelions than cultivating popular greens such as spinach and cilantro. “We have good demand for it,” he explains. “It’s not a big market, but we grow enough to saturate the market.”

This kind of tactic dovetails with Wiswall’s philosophy of farming “smart, not hard.” By microtargeting their efforts, he’s shown, savvy farmers can flourish crop by small crop.

This November Chelsea Green will release the fruit of Wiswall’s experience, The Organic Farmer’s Business Handbook, complete with worksheets on CD-ROM. With numerous speaking and consulting gigs under his belt, Wiswall feels qualified to offer advice on one of the riskiest — and, around here, trendiest — professions. “[The book] will hopefully keep people from repeating the same mistakes that I made, and give them a leg up and some shortcuts so they can get to a profitable state much quicker than they would have otherwise,” he says.

But the road from starting a farm to having enough knowledge to fill a book was a long one. “It’s only after 28 years of [farming] that I felt like I could do it,” says Wiswall. “Back when I started, I didn’t know what I was doing. I was 24 years old, very green and full of energy.”

In 1981, the recent graduate — known to his friends as “Wiz” — was working at a bike shop in Middlebury and pondering his future. “All my friends were going off to graduate school or doing these straight jobs, and I was thinking, I don’t really want to do any of that,” he recalls.

Then he got two simultaneous job opportunities. One was to manage Middlebury’s semesters abroad in Nepal; the other, to join four business partners in buying and revitalizing the historic Cate Farm. Inspired by the back-to-the-land movement and Wendell Berry’s writing, Wiswall chose farming over roaming the globe. He moved into the house on the Plainfield property, which was farmed by the Cate family from 1793 until 1901.

A dirt road leads visitors through a picturesque covered bridge and into sight of the farm, which is situated on a bend of the Winooski River. Flood plain accounts for many of the farm’s 148 acres. Its centerpiece, an aged, stately, post-and-beam barn, was built to hold tons of loose hay — and at one time, ice harvested from the river. Despite predating Napoleon, the farm has a modern bohemian pedigree: In 1964, it became part of Goddard College, and numerous Bread and Puppeteers made their home in the farmhouse in the 1970s. “I think it was kind of zoo-y,” Wiswall guesses.

Even though he had business partners, Wiswall was Cate’s sole farmer from the start. “The partnership was structured so I could conduct farm business, and the other partners would do other things: cooking, photography, carpentry,” he explains. The first year, he recalls, “We started small, with 1 acre, and doubled in size until we reached 16 acres.”

After about a decade, though, the original group began to drift apart. “Other people had other lives, got married, had kids, settled in different places,” Wiswall says. “Living on Cate Farm was not going to be in the cards.” But it was for Wiswall, who decided to take a huge plunge: He took out a $190,000 bank loan and offered to buy out his partners. All accepted.

The massive debt gave Wiswall an impetus to put his analytical skills to use. “I’d put my neck very stretched out on the chopping block and had to prove to the bank, as well as to myself, that I could make money farming,” he says. “The pressure was on. My focus was to be as sharp a farmer as I possibly could and pay down the loan as fast as I could.”

The former environmental science major knew how to run numbers. But agriculture is a hands-on endeavor, leaving farmers little time to track their profits. “You get lost in the frenetic pace of farm life in the summer,” Wiswall attests. “You don’t know if the time you’re putting into carrots — growing, harvesting, washing, storing, delivering — is justified by the sales. Thank God for the IRS,” he adds. “I never thought I’d say that, but if it weren’t for the IRS, [most farmers] wouldn’t be doing a big accounting even once a year.”

For a full growing season, Wiswall took detailed notes on intake and expenditure. He emerged with a surprising conclusion: Some of the most sought-after crops are financial dead weight. Colorful heads of heirloom lettuce, for example, required too much labor for the price. “Basically, I just dissected it,” Wiswall recalls. “There are some crops out there that are just cash cows, and others that were bleeding me to death.”

Armed with a calculator and notes, Wiswall transformed Cate Farm from an operation that barely scraped by into a profitable one. “I could make my debt payment, have money for vacations, build for the future,” he says. “It was hugely liberating.”

In that same year, 1993, Wiswall met Sally Colman and her young son, Peter. She moved to the farm in 1995, and the pair married in 1999.

In 2002, the couple pared down the number of products they were growing in an effort to reduce their weekly work hours. They eliminated their 6-year-old farm share because it required producing too great a variety of veggies. “The concept is great,” says Wiswall of community-supported agriculture, “but at the time, I wanted to work less. As I become older, free time becomes more valued.”

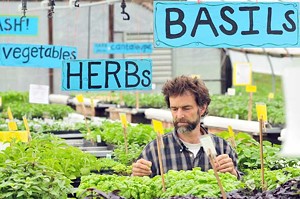

Nowadays, Wiswall and Colman thrive in tightly defined seasonal markets. In the spring, they sell seedlings to the general public; in the summer, they do big business in greenhouse-grown tomatoes; and throughout the fall and winter, they offer root veggies and their trio of medicinal herbs — dandelion, burdock and echinacea. They focus on wholesale deals with Hunger Mountain Co-op and area restaurants, but also maintain some out-of-state accounts. They supplied medicinals to Tom’s of Maine before that company changed hands.

You will find kale and cucumbers on Cate Farm, but not en masse: Colman and Wiswall sell that produce at the Montpelier Farmers’ Market and use it in their own meals.

The pair and their children and staff still work a lot, dividing up the labor: “[Sally] does all the greenhouses; I do all the fieldwork and physical-plant kind of things,” Wiswall says. But nowadays, farming is “less management intensive,” he adds. “I don’t feel like I’m juggling 10 balls in the air and trying to keep them from dropping.”

Their careful organization is visible in Cate Farm’s seven greenhouses, grouped behind the farmhouse. Three are dedicated to a single variety of tomato, which will eventually grow taller than the thin, bearded, 6-foot-2-inch farmer. The odorous plants reach that stature thanks to warmth, consistent watering via a timed drip system, and a series of strings to tie up the top-heavy, fruit-laden branches. Two other greenhouses boast the diverse produce destined for market, while the final two are reserved for seedlings.

Conservative as their approach may seem, Wiswall and Colman do experiment. Their latest project: grains. Last year they purchased a combine that allows them to harvest acres of soil-building cover crops — including oats, spelt and rye — for seed. “We’ll grow varieties of wheat and barley this year to try using ourselves and to sell,” Wiswall says. “Bakers are looking for local grains.” Plus, he points out, “It’s really fun to see a field of wheat.”

Tools and gadgets are another weapon in Wiswall’s “smart farming” arsenal. For example, he heats the concrete floor of his workshop, making it possible to start certain plants there in the winter rather than heating a whole greenhouse.

Working with a friend, Wiswall retrofitted a spindly 1952 tractor with a battery pack. Running the machine now costs a fraction of what it did, and there are fewer moving parts to break. “It’s quiet; it doesn’t pollute; you don’t smell exhaust,” he says.

Besides the battery power, Cate Farm relies on recycled frying oil to run two diesel tractors and the greenhouses. One room holds 4-and-a-half-gallon containers of viscous restaurant detritus, ranging in color from gold to nearly black. “We get it from J. Morgan’s and NECI,” says Wiswall. “Go there and eat fries!”

But the farm’s coolest innovation may be a lower-tech one. The two greenhouses dedicated to seedlings are connected by a pipe, which Wiswall has turned into a trolley line for a cart that holds up to 25 loaded flats at a time. Between the two greenhouses, the pipe curves by a spot where customers can wait with their cars and load up — a sort of eco-friendly assembly line.

Although the aim of his book is to help organic farmers make more money, Wiswall doesn’t suggest he’s the only one around with the smarts to turn crops into cash. “Even 30 years ago, the people attracted to the organic farming movement were first-generation farmers with college backgrounds,” he recalls. Today, he still sees savvy youngsters opting to make a living off the sweat of their brows: “When people are dissatisfied with the lifestyle they’re leading, they want to return to more traditional roots, something visceral.”

But returning to tradition doesn’t mean plowing the earth and hoping for the best. “It’s our own head set that keeps us from realizing we can make money farming,” Wiswall opines. This farmer’s crops may be fuzzy, but his brain sure isn’t.

Home and Garden Issue

Mud season is over, spring has sprung, and all across the state Vermonters are … back in the dirt. Soil, that is. Tilling it, planting flowers and food in it, and, in the case of the Vermont Compost Co., selling it. In this issue we go indoors to consider low-budget decorating tips and eco-friendly window treatments; outdoors to visit a profitable Vermont farm and a wannabe eco village; and underground to a root cellar. Finally, master gardener Barbara Richardson talks container crops, because not all of us can plot our produce. No place like home.

This is just one article from our May 13, 2009 Home and Garden Issue. Click here for more Home and Garden stories.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Q&A: Howard Fisher Delivers Meals on Wheels With a Side of Good Cheer

Dec 20, 2023 -

Video: Howard Fisher Delivers Meals on Wheels

Dec 14, 2023 -

Q&A: Alexis Dexter Rescued 57 Shelter Cats During the July Flood

Sep 13, 2023 -

Video: Two Months After the Flood, Alexis Dexter Rebuilds Kitty Korner Café in Barre and Continues to Rescue Cats

Sep 7, 2023 -

Did Your Garden Flood? Here's What to Know

Jul 28, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.