Published December 2, 2019 at 2:16 p.m.

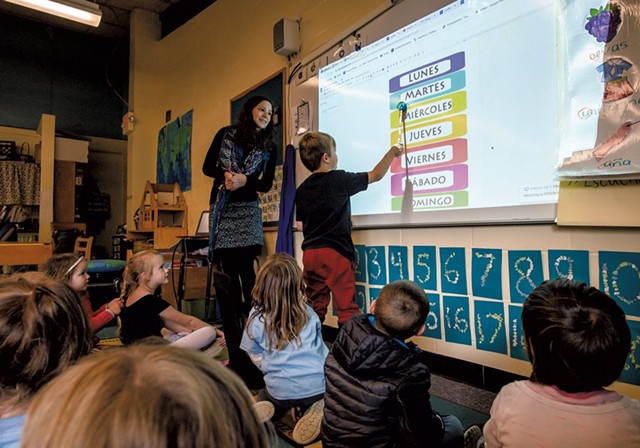

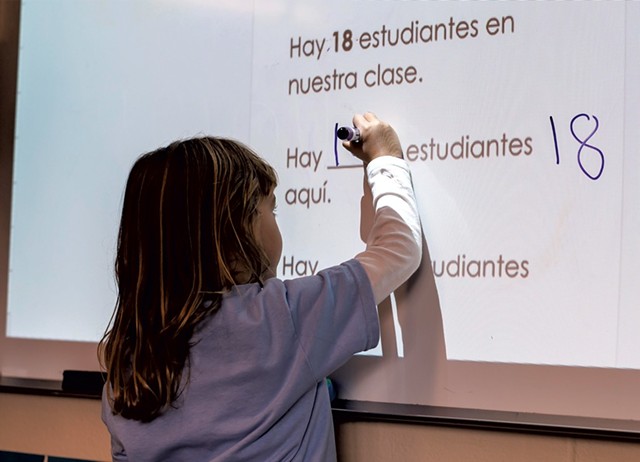

Like many elementary school students in Vermont, Sylvan Ross' 18 kindergartners at Jericho Elementary School begin their day with a class meeting. They circle up on a colorful world map rug, where they read the morning message, greet each other and participate in a playful activity. Like their peers around the state, their academic day will consist of lessons in reading, writing, math, social studies and science.

With one fundamental difference. Their classes are in Spanish. In 2017, Mount Mansfield Unified Union School District launched Vermont's only Spanish immersion program, which now includes students in kindergarten, first and second grades. Housed at the preK-4 Jericho Elementary School, the lottery-based program accepts students from the five towns in the school district, which also includes Richmond, Huntington, Underhill and Bolton.

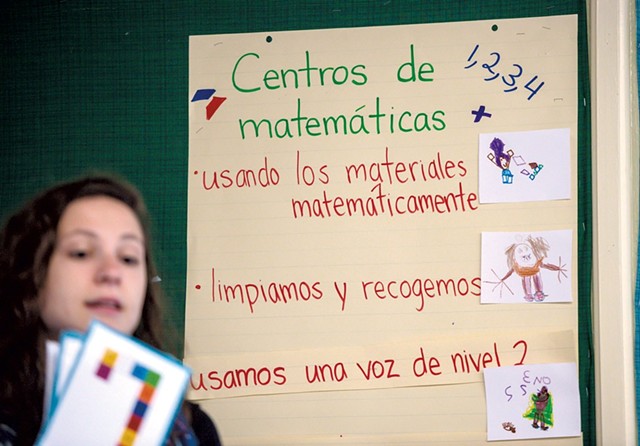

Immersion refers to a method of foreign language instruction in which the language is used as a tool to teach the curriculum, rather than being taught as an isolated subject. Eighty to 90 percent of the school day for Ross' students — as well as the students of first-grade teacher Christie Moulton and second-grade teacher Julia Menendez — is spent reading, writing and speaking in Spanish. During lunch, recess and the unified arts classes — PE, music and art — students speak English.

Because the bulk of the day is en español, and all students in the program are native English speakers, the program is classified as full, one-way language immersion. In dual, or two-way immersion — the most commonly found immersion program in schools across the country — native English speakers and native speakers of another language are in the same class, and instruction takes place in both languages. These programs were initially created as a way to provide bilingual instruction to English learners. A 2017 research brief from the Rand Corporation found between 1,000 and 2,000 dual-language programs in the U.S. Beyond that, there is little data about the number of language immersion programs in the country, said Lisa Tabaku director of global languages and culture at the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Applied Linguistics. Though one-way programs are "few and far between," she said, her organization has seen a growing interest in recent years, which she attributes to people's understanding of the importance of being bilingual both globally and domestically. In fact, the Center for Applied Linguistics is currently consulting with the Montpelier Roxbury Public Schools as it explores adding a language immersion program in the future, said superintendent Libby Bonesteel. Further evidence of the renewed interest in language education, Tabaku added, is the Seal of Biliteracy, which California established in 2011 to award students who graduate from high school with proficiency in two or more languages. Since then, 36 additional states and Washington, D.C., have adopted it. (The seal is under consideration in Vermont.)

Ross' kindergartners call her Tía Ross — a term of endearment in Spanish that translates to aunt — and greet each other with an Hola! or Buenos Dias! The picture books in their classroom have familiar pictures on their covers, but, upon closer inspection, have titles like La llama llama rojo pijama and Buenas noches, Luna. The math curriculum is the same one that other teachers in the school use, just the Spanish version.

On the last Monday in September, Ross has written the morning message — all in Spanish — on a piece of chart paper, with a question at the bottom: "¿Te gusta el otoño?," which translates to "Do you like autumn?" Students and adults in the room put a check mark in the "si" or "no" column, then Ross poses the question to each child, and they respond "Si, me gusta" or "No, me gusta." Then they count together in Spanish to find out how many "si" and "no" check marks there are. The "si" marks beat the "no" marks, 19-3.

When Ross takes out an oversized picture book with a butterfly on the cover to begin reading to the class, a little girl exclaims, "That's big!," then quickly corrects herself. "Grande!" she says.

"Es muy grande," Ross replies.

El Origin

Mount Mansfield Unified Union School District may seem like an unlikely place to launch a language immersion program. Its five elementary schools, two middle schools and one high school serve around 2,600 students in total. Ninety-seven percent of them are white, 93.2% speak only English at home, and only 2.1 percent live below the poverty line, according to the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics. In other words, there is little linguistic, cultural or socioeconomic diversity.

But parents in the district are involved, educated and interested in innovative educational programs for their children. Parents like Camille Campanile. Her first grader, Alessandro, who goes by Sasha, is in his second year of Spanish immersion. She said she was drawn to the program for several reasons. She'd learned through research that, in terms of brain development, elementary school is a prime time to become fluent in a new language. And she was excited about the opportunities that Spanish fluency would afford her son, from internships and jobs, to attending a foreign college and traveling abroad.

"Beyond his development," she added, "from a cultural and social justice standpoint, I love that he's learning Spanish in a time when so many people are closed-minded when it comes to immigration. It almost seems like a political act."

Cultural considerations were also important to Dayva Savio when she enrolled her son, Buck, in the program last school year. The summer before Buck started kindergarten, the family moved to Jericho from Los Angeles, where Spanish was ubiquitous. Coming from a diverse environment, Savio saw the importance of giving her son a multicultural education, with Spanish language and culture woven into the curriculum, rather than learning about it as something that deviates from the norm.

In 2015, it was a small group of parents, along with teachers, school board members and Jericho Elementary School principal Victoria Graf who began researching language immersion programs to see whether implementing one in the district would be feasible and beneficial.

In February 2016, the group presented a white paper to the school board, making a case for the program. "Our country faces a need for proficiency in non English languages, and it is reported as one of the greatest needs for business, diplomacy, education, national security and social services," the paper stated. The group cited research showing that learning a foreign language at an early age boosts critical thinking skills, creativity, and cognitive flexibility and, in the early elementary grades, has a positive impact on academic achievement and correlates with higher math and reading test scores. Learning a new language before puberty has been linked to fluency, better pronunciation and the ability to switch between languages.

The committee considered a French language program, given Vermont's proximity to Canada, but settled on Spanish for a few reasons. First, there were more quality educational materials — including curriculum and children's books — available in Spanish than in any other foreign language. Second, Spanish is the most commonly spoken language, after English, in the United States.

The school board approved the proposal, and the district partnered with Middlebury College's language program to hammer out implementation. The Spanish immersion program began in September of 2017 with 17 kindergarten students. Those students are now in second grade, and a new kindergarten class has been added each year.

La Implementación

Families who want to enroll their children in Spanish immersion enter a lottery. This school year, 32 children applied for 18 slots. To ensure the lottery is fair, the district films the names being drawn, said Graf. Families are notified if they have been admitted in March. Students who aren't part of the immersion program still get weekly Spanish instruction.

When children enter kindergarten, most don't have any foundational skills in Spanish, so "a lot of what they're doing is guessing," explained Ross. To keep children engaged, teachers use a variety of techniques. One is a method called total physical response, which involves using motions that correspond with words to create a connection between speech and action. For example, a teacher might flap her arms like wings as she says the word pájaro, or bird. When teachers need to speak English to students — like during a fire drill — they don a special scarf. Reading is taught through learning letter sounds and sounding out words, similar to how it's taught in English. Students' receptive language, or the ability to understand Spanish, is initially stronger than their expressive language, or their ability to speak Spanish, said Graf. In second grade, speaking is "a major goal," said Menendez.

Just as important for effective instruction, said teachers, is that kids feel excited about learning Spanish. If students feel like they're in a high-pressure situation, their "affective filter" goes up, and they won't want to take risks, said first grade teacher Moulton. "We never want to make students feel bad for using their first language." When students speak to her in English, she'll simply repeat what they said back to them in Spanish or, if she knows it's something the student knows how to say in Spanish, remind them of that fact. In order to keep things fun and engaging, teachers incorporate puppetry, songs and movement throughout the day.

El Futuro

Like any new program, said Graf, "we're learning as we go." Teachers observed that Spanish immersion kindergartners seemed more tired in the afternoon than nonimmersion kindergartners, so more hands-on learning and choice time is now incorporated in the latter part of the day. In the first year of the program, the paraprofessional in the kindergarten immersion classroom didn't speak Spanish. Teachers soon realized it was important to have another adult in the room who could model Spanish conversation with the teacher. This year, the two paraprofessionals who support the three Spanish classrooms are fluent Spanish speakers. The school is exploring new assessment tools to add to the ones they currently have in place, in order to collect more data on how students are progressing.

The district has looked to the Spanish immersion program in the Mendon-Upton Regional School District in Massachusetts as a resource. The district, which has similar demographics to Mount Mansfield Unified Union, established its Spanish immersion program 22 years ago and has turned out hundreds of bilingual students. Through the years, it has increased in popularity, said Mendon-Upton kindergarten immersion teacher Olga Grau. In her district, students in grades K-2 receive 100 percent of instruction in Spanish. English is gradually introduced starting in third grade, so that by fifth grade, instruction is half Spanish and half English. That's because public school students are required to take standardized tests in English, and the district wants to ensure they are prepared. Mount Mansfield Unified Union plans to follow a similar model, with some English instruction being introduced in either the second semester of second grade or first semester of third grade.

As the program grows by one class each year, it's taken on a more prominent presence in the school. Walk down the hallway and you'll hear more Spanish than you did two years ago, said Merideth Chaudoir, who has a kindergartner and second grader in the program (younger siblings of immersion students are guaranteed admission). The school also has more resources and books in Spanish, and even the town librarian has ordered more Spanish language children's books. "It just keeps getting better and better," Chaudoir said.

The program will run through at least fourth grade and possibly fifth, with the goal of producing bilingual and biliterate students, said Graf. After that, there are question marks. Families said they're hopeful that in middle and high school, the district will provide immersion students with opportunities to extend their learning, through Spanish literature classes or independent study, for example. It's been shown that it's important to regularly speak a foreign language in order to retain it, said Campanile. "I don't want to see this incredible opportunity for kids to become fluent lost."

Graf said the district is currently researching options to support and extend the learning of Spanish immersion students in middle school. At Mount Mansfield Union High School, students can study Latin, Spanish or French — with Advanced Placement options in both Spanish and French.

Parents who have children in the Jericho program have been "incredibly supportive" and committed to the program's success, said Graf. On children's birthdays, Chaudoir said, families in her daughter's class donate a Spanish-language book to the class. Last spring, the district hosted a well-attended course for Spanish immersion parents to learn beginning conversational Spanish. Over the summer, parents of this year's first-grade class arranged for a bilingual educator to teach a weekly Spanish lesson for kids, weaving in music and art. Some families have visited Spanish-speaking countries on vacation. Said Campanile: "Most of us are trying to tag along in the wake of our kids."

Her first grader Sasha's Spanish skills have already surpassed those of her two middle schoolers and high schooler, Campanile said. Sasha even helps his seventh-grade sibling with pronunciation. "He loves going to school. He loves that he's learning Spanish. It makes him feel so empowered."

Sasha's teacher, Moulton, who taught in a dual immersion classroom in California before moving to Vermont, thinks that in addition to learning a new language, immersion students are also getting an expanded world view. "I love that students get to think and ask what language they speak in [different countries], not assuming the world is made up of people just like them," she said. "Education can be a window out into the bigger world. Why not provide that for students in a rural area?"

This article was originally published in Seven Days' monthly parenting magazine, Kids VT.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Three Questions for Kate Blofson of Jericho’s Born to Swarm Apiaries

Apr 23, 2024 -

A Jericho Church Building Has Been Transformed Into a Teen Thrift Store and Hangout

Jan 31, 2024 -

Q&A: Carpenter Dario Guizler Renovates Old Houses and Mentors Fellow Immigrants

Jan 17, 2024 -

Video: Carpenter Dario Guizler Builds a Life in Burlington

Jan 11, 2024 -

Jericho’s Brew House Coffee Heats Up With Cold-Brew

Oct 3, 2023 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.