Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Afford-Ability: Can Gov. Phil Scott Deliver a Bigger Slice of the Pie?

Published January 11, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 6, 2020 at 8:34 p.m.

click to enlarge

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Gov. Phil Scott signing an executive order calling on state government to make Vermont more "affordable"

For Ellen Baier, "affordability" isn't just a buzzword.

The 34-year-old mother of one has a college degree and a steady job. "But I still feel broke a lot of the time," she says. "I'm basically just keeping my head above water."

Every month, the Burlington resident spends $924 — close to half of her take-home pay — on childcare. Much of the rest, she says, goes to food, transportation and necessities for her 3-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Audrey.

"I rely on my partner for everything else," she says. "I'm really lucky we're in a good relationship and things are going well, because, even if I wanted to, I couldn't leave."

Baier, who grew up in St. Louis, loves living in Vermont and the "cultural touchstones" it provides. But, she admits with resignation in her voice, "It's not very affordable."

She's not the only one who feels that way. In recent years, "affordability" has emerged with new resonance and omnipresence in Vermont's civil discourse. But its simple, literal definition — the state of being within one's financial means — belies a more complicated debate over the causes of and remedies for Vermont's so-called "crisis of affordability."

This isn't just a matter of semantics. Over the past four years, Berlin Republican Phil Scott has placed the word — and the emotions it provokes — at the center of his political platform.

"While campaigning, a recurring message I heard — and I'm sure many of you heard — was the anxiety over affordability," he told the Vermont Senate as far back as January 2013, when he began his second term as lieutenant governor.

Since then, Scott's diagnosis of the state's economic condition has barely budged. But, now that he's become Vermont's 82nd governor, he's finally in a position to write a prescription.

Last Thursday, Scott declared in his inaugural address at the Vermont Statehouse that he would immediately sign an executive order directing state government to focus on "strengthening the economy, making Vermont more affordable and protecting the most vulnerable." His newly appointed cabinet members, seated in the House balcony, rose from their seats with applause. Like a wall of water, the standing ovation poured over the balcony and swept through the chamber.

Who, after all, wouldn't want to make Vermont more affordable?

But when the applause dissipated, Scott moved on. Left unsaid was how his administration would achieve all that — and what he even meant by "affordable."

"I think the key question is: affordable for whom?" says Christopher Curtis, an antipoverty advocate who spent the past decade working for Vermont Legal Aid. "The challenge of the term 'affordability' is that a millionaire can feel like things aren't affordable. Everyone can cast their own values on the term."

"I think the key question is: affordable for whom?" Christopher Curtis, Vermont Legal Aid tweet this

That ambiguity is advantageous in a political campaign, when the goal is to appeal to as broad a swath of the electorate as possible. But it's problematic in governance, when promises suddenly come due.

"Most of his career, Gov. Scott has had the luxury of taking vague positions," says Conor Casey, executive director of the Vermont Democratic Party. "For the first time, he's going to have a record that he's going to need to run on in the future."

Baier, the Burlington mother, is hoping that Scott's "affordability agenda" will help her hold her head above water. She thinks that it might. After attending a forum last fall during Scott's run for governor, Baier came away with the impression that he "cares about making childcare something people can access and use and afford."

To achieve that goal, she believes, the state must increase the childcare subsidies it provides low- and middle-income families. Currently, only 23 percent of families seeking care receive some form of assistance, according to a recent study commissioned by the legislature.

In his inaugural address, Scott sounded open to the notion. "Investment in early education is a proven approach to reducing special education and health care costs," he said, drawing another standing ovation — this one emerging from the Democratic seats in the House.

But in an interview with Seven Days earlier that week, Scott suggested quite the opposite. He said the state didn't have the money to invest in higher subsidies and should focus instead on "trying to provide for better-paying jobs, so that people can afford childcare."

"In time, hopefully, reimbursement will become better, when we have more revenue growing organically," he said. "But not in the short term."

Vermont could not afford, Scott seemed to be saying, to make Vermont more affordable for Baier.

A Taxing Debate

Politicians, particularly on the left, have for decades used the word "affordable" to describe specific policy priorities: "affordable housing," "affordable health care," "affordable childcare" and so on. But in Vermont, at least, it was Scott and his fellow Republicans who popularized "affordability" as a stand-alone noun.

The word began cropping up in 2013 — first in Scott's speech to the Senate and later in statements by House Minority Leader Don Turner (R-Milton) and future gubernatorial candidate Bruce Lisman. When David Sunderland ran for chair of the Vermont Republican Party that October, he argued that when it came to "jobs, health care, education and affordability," Vermont Democrats were "out of touch and out of the mainstream."

Soon, "affordability" was everywhere. In 2014 alone, the GOP issued more than 40 press releases employing the term. And when Scott launched his campaign for governor in December 2015, he used some iteration of the word no fewer than five times in his speech to supporters.

"We have tremendous opportunities ahead of us, but many Vermonters feel trapped by a very real crisis of affordability," the 58-year-old construction executive said at the Sheraton Burlington Hotel & Conference Center.

Scott says he can't quite remember when he started using the word, but he thinks it came from his Everyday Jobs Tour, during which he would spend a day bagging groceries, delivering home heating oil or toiling away at an ice cream plant.

"'Affordability' came organically from the people,'" he recalled in last week's interview, three days before taking office. "It's just something that I kept hearing over and over. Maybe I heard it in the news reports or read it, but it was more what I was hearing across Vermont."

Sitting at a conference table in his State Street transition offices, Scott struggled to identify precisely what the word means.

"It's clearly difficult to define the term in a sentence or two, because it does mean different things to different people," he conceded.

But the governor-elect seemed to know it when he saw it. It's what keeps a 71-year-old St. Johnsbury man from retiring from a car dealership, he said. And it's what forces Vermonters to work "two and three jobs" because they're having trouble "paying their property taxes or paying their rent or paying their mortgage or paying their fuel bills."

Scott seemed more confident describing what he views as the causes of the "affordability crisis": slow population growth and an onerous tax burden.

"I think [taxes] also lead to the cost of other products increasing as well, so it affects the cost of every product and service across the board," he said.

While Scott focuses on the costs Vermonters face, state Auditor Doug Hoffer argues that "the equation has two sides — and it's really important to talk about wages."

In other words, affordability isn't just about how much Vermonters are spending. It's also how much they're making.

A new report by the Public Assets Institute, a progressive think tank based in Montpelier, makes clear that Vermonters, like most Americans, are stuck in neutral. Despite a slight uptick over the past two years, the state's median household income, adjusted for inflation, "has remained essentially flat since at least 2000," the report found, citing U.S. Census data. And while income has surged for the wealthiest Vermonters, most others are only now earning close to what they made before the 2008 financial crisis.

For those supporting a family, that's often not enough.

According to the legislature's nonpartisan Joint Fiscal Office, a single parent with two children must make at least $4,630 a month to provide for even the most basic needs, such as food, housing, childcare and health insurance. That figure jumps to $5,217 in Chittenden County.

Nearly three-quarters of such parents make less than that, according to the Public Assets Institute, while close to 70 percent of single parents with one child can't afford those basic needs.

"If people put in a 40-hour week, they ought to have enough money to be able to support a family," says Jack Hoffman, a senior policy analyst with the Public Assets Institute. "People just need more money in their pockets. It's the way to fix affordability."

Waging Battle

Last Wednesday, on the opening day of the legislative biennium, some 30 activists and lawmakers stood behind a podium on the steps of the Vermont Statehouse in a cold, light rain. Some held a long banner featuring 13 faceless silhouettes and the words "Together We Win." Others held signs reading "Raise the Wage."

Rights & Democracy, a Burlington-based advocacy group, had organized the rally to promote its "People's Agenda" — and to put the incoming Scott administration on notice that it would not accept cuts to social services.

Halfway through the noon event, Green Mountain Self-Advocates outreach director Max Barrows approached the podium, bundled in a red overcoat and a fur hat with earflaps. The Worcester resident identified himself as "a person with autism" who relies on developmental-support services to help him do his job.

"But support workers do not make a livable wage. Sometimes they have no choice but to take another job for better pay," he said. "A livable wage will go a long way to reducing staff turnover. We must raise wages."

Scott, too, wants Vermonters to make more money. But he disagrees with Barrows, Hoffman and Hoffer that the way to achieve that goal is by raising the minimum wage.

"I believe that just adds to the cost, so it furthers the problem," Scott said during last week's interview. "I just believe that it has to come the other way — that you need more economic activity in order to bring better wages and higher wages."

Scott's "affordability" theory is somewhat circular in nature: Goods and services are too expensive, which prompts workers to flee the state, which increases the tax burden on everybody else, which makes goods and services more expensive.

But, as Hoffer points out, the data don't support those conclusions. For one thing, prices in Vermont are almost exactly the national average, according to a state-by-state index by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

To be sure, there are cheaper places to live. The cost of goods and services in Mississippi and Arkansas is just 87 percent of the national average. But in most northeastern states, it's actually higher than Vermont: 105 percent in New Hampshire, 108 percent in Connecticut and a whopping 116 percent in New York.

Story continues below graphic.

Despite all the ink spilled over the state's supposedly high tax burden, Vermont's effective tax rate is roughly average. And according to a 2015 study by the left-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, "Vermont's tax system is among the least regressive in the nation because it has a highly progressive income tax and low sales and excise taxes."

That does not mean state government is flush with cash. As Scott noted in his inaugural address, budget pressures continue to outpace tax revenue in Vermont — this year, to the tune of "at least $70 million." Contributing to the costs are the programs Democrats have promoted to make the state more affordable — a circular logic of their own.

Campaigning for governor last year, Scott hinted at how he might tackle budget shortfalls: by "containing the cost of our generous social welfare programs." Of course, doing so runs the risk of making the state even less affordable — at least to the low-income Vermonters who rely on such programs.

Scott maintains that he can have it both ways — that he can cut state spending without affecting services. Asked specifically whether his budget would hold low-income Vermonters harmless, he said, "On a fairness standpoint, yes. We want to take care of the most vulnerable. We have an obligation to do so. But, at the same time, we want to be sure that services are being delivered in the most cost-effective way possible."

House Speaker Mitzi Johnson (D-South Hero) is skeptical.

An hour after Scott's inaugural address last Thursday, she stood outside her Statehouse office and ticked off the commitments the governor had made in his speech: "Increased access to early education, more affordable higher education, lots of affordable housing and seriously taking on cleaning up our waterways," she said, a look of exasperation on her face.

"If there's a way to do all that within our existing budget, I have not found it in 10 years on the budget committee," she said. "And I have looked very hard."

The 'Other' Vermont

click to enlarge

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Mari Cordes of Rights & Democracy speaking at a rally last Wednesday outside the Statehouse

In his opening remarks last week to the Vermont Senate, newly elected President Pro Tempore Tim Ashe (D/P-Chittenden) seemed to reject the notion that all Vermonters share a common "crisis of affordability." On the contrary, he argued, there are two separate Vermonts, whose residents live vastly different lives.

There are those, he said, who enjoy the food, culture, safety and education that privilege confers. "But then there's the 'other Vermont,'" he continued. "The other Vermont is inhabited by people experiencing a very different kind of life." Global trade has cost them their factory jobs, he said, while drug and alcohol abuse has disproportionately ravaged their families.

"Above everything else we work on," Ashe told his colleagues, "we must in every policy area endeavor to create just one Vermont — a place where the dumb luck of who you've been born to" does not determine your lot in life.

Like Ashe, Sen. Richard Westman (R-Lamoille) resists the "affordability" label popularized by his party-mate, Gov. Scott.

"I think it's more income inequality," he said.

When Westman was growing up on his family's Cambridge dairy farm, he recalled, "You had very poor people and very wealthy people on the one dirt road I lived on. You had to face those people day to day." But these days, he said, the rich have become richer and the poor have become poorer — and they no longer live side by side.

"We aren't facing those people now," he said. "We're separating, and I think it's furthering that income gap."

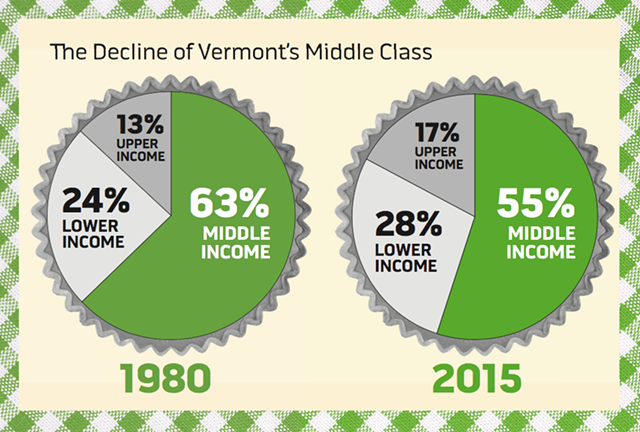

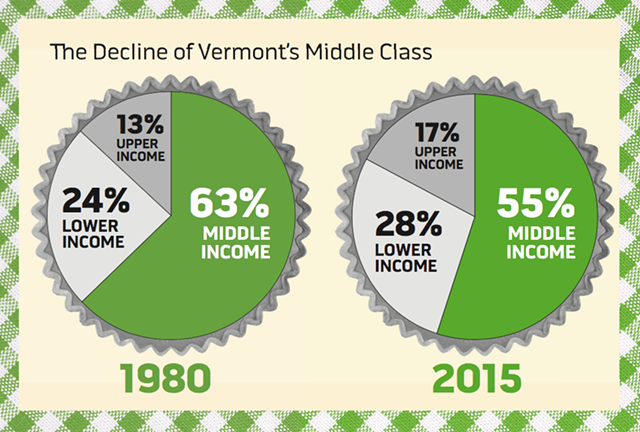

Westman is right that in Vermont, as in the rest of the country, income has become more stratified. Since 1980, according to the Public Assets Institute, the state's middle class has declined by more than 12 percent, while the ranks of the rich and poor have increased. In 2015, the average family of four in Vermont's lowest-earning 20 percent made just $27,806, while those in the top 5 percent earned $332,271.

click to enlarge

- Diane Sullivan

- Income Data: Public Assets Institute analysis of U.S. Census microdata. Middle income ranges from 66.7 to 200 percent of median household income.

Despite a one-year drop in 2015, poverty has been on the rise in Vermont for most of the past 15 years. According to Census data, some 60,000 Vermonters — nearly one in 10 residents — live in poverty, including 15,000 children and close to half of single mothers with children under 5.

"Affordability" and "income inequality" are not necessarily contradictory concepts. By definition, those at the bottom of the income ladder can't afford to live in Vermont — or anywhere, for that matter. But when Scott uses the term "affordability," he says he's mostly thinking of the middle class, whose needs are not the same as the impoverished. Asked last week whether he had any specific proposals to combat poverty in Vermont, Scott demurred, reverting instead to his standard talking points.

"Again, just having economic opportunity," he proffered. "To really focus on the economy and try to drive the economy, focus on that, will provide more opportunity, provide for better jobs, I believe."

Those on the front lines of Vermont's battle against poverty are seeking something more specific than that. They point to four of the biggest expenses in the Joint Fiscal Office's "basic needs" budget — housing, childcare, health insurance and transportation — and argue that the state must focus on reducing those burdens.

"Simply cutting taxes is not going to solve the problems that confront us, because they're more complex than that," says Curtis, the antipoverty advocate.

There are any number of ways to address those problems, but many of them are expensive — and Scott appears to have little appetite for further government investment. Still, Curtis is hopeful that Scott and the Democratic legislature can find common ground — for example, around housing.

According to Census data, a majority of Vermonters earning $50,000 a year spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing — the threshold experts use to determine its affordability. Only one county in New England has a higher percentage of priced-out renters than Chittenden County.

"Affordability," says Champlain Housing Trust spokesman Chris Donnelly, necessitates reasonably priced housing for everybody.

"Without having a place to call home," he says, "there's no place to think about going to college, getting a better education and improving your place in the workforce."

'Boatload of Privileges'

When it comes to housing, Baier considers herself lucky. Her boyfriend owns a home in Burlington's New North End, sparing her a major expense.

She's lucky in other ways, too. Though it took her eight months — starting when she was pregnant — Baier managed to secure a spot for her daughter, Audrey, in one of the state's best childcare centers, at the Lund Family Center. Conveniently, it's right down the road from the South Burlington studios of WCAX-TV, where she works in sales.

Baier knows she could find cheaper childcare, but she considers the expense worth it. She briefly sent Audrey to a lower-rated facility and "cried about it a lot because I knew that at least one of the people there who was in infant care was a smoker."

"I mean, there's places to find a bargain — and that's generic cereal, not childcare," she says.

Baier recognizes she has "a boatload of privileges" compared to other Vermonters, including the childcare workers who look after Audrey at Lund.

"Even though they're at one of the best programs in the state, they still can't make rent without a second job," she says. "I mean, I wish I could pay more."

Though she wonders sometimes whether it would be more affordable to live elsewhere, Baier doesn't think she could leave.

"Not really. No," she says. "It matters to me that people in Vermont care."

Disclosure: Tim Ashe is the domestic partner of Seven Days publisher and coeditor Paula Routly. Find our conflict-of-interest policy here: sevendaysvt.com/disclosure.

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Politics, Phil Scott, affordability, cost of living, minimum wage, Tim Ashe, Mitzi Johnson, interactive

More By This Author

About The Author

Paul Heintz

Bio:

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Speaking of...

-

Q&A With the Candidates for Governor

Sep 17, 2024 -

Cleanup Begins as Vermont Recovers From Severe Flooding

Jul 12, 2024 -

From the Publisher: Football Fans

Jun 26, 2024 -

Monkton Man Cited for Allegedly Threatening Lawmaker

Jun 21, 2024 -

Vermont Lawmakers Override Six of the Governor's Eight Vetoes

Jun 17, 2024 - More »

Comments (6)

Showing 1-6 of 6

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Public Safety Forum in Burlington Draws a Crowd News

- 2. A South Burlington Lot Was Slated for Housing — Until the Landlord Next Door Stepped In Development

- 3. Surging Cyber Scams Leave Older Vermonters Destitute, Frustrated and Saddled With Tax Debt This Old State

- 4. Cities and Towns Plead for State Help in Handling Homelessness Housing Crisis

- 5. Pawlet Selectboard Member, His Wife and Stepson Found Fatally Shot Crime

- 6. A T. rex Has Gone Missing. Neighbors Are Hoping to Track It Down. True 802

- 7. Police Arrest Son of Slain Pawlet Selectboard Member For Triple Murder Crime

- 1. Surging Cyber Scams Leave Older Vermonters Destitute, Frustrated and Saddled With Tax Debt This Old State

- 2. Some Residents of Greensboro Are Fighting an Affordable Housing Proposal Housing Crisis

- 3. Readers Weigh In on 'Bad News Burlington' Opinion

- 4. Vermont Schools Are Banning Smartphones to Limit Distractions Education

- 5. College Cannabis Course Is Growing Vermont's Weed Workforce Education

- 6. Gov. Scott, School Leaders Raise Alarm About Next Budget Season Education

- 7. Vermont Still Allows Farmers to Spread Contaminated Sludge on Fields Environment