click to enlarge

- Oliver Parini

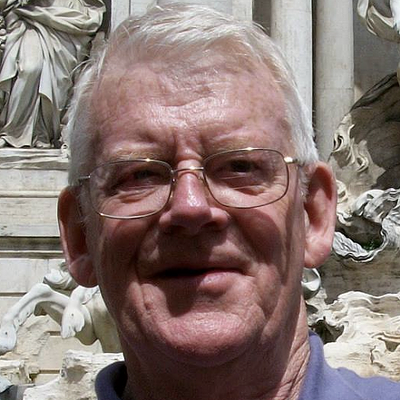

- Tim and Jess Lahey

This "backstory" is a part of a collection of articles that describes some of the obstacles that Seven Days reporters faced while pursuing Vermont news, events and people in 2022.

Throughout the pandemic, I regularly queried Tim Lahey, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

"Whaddya think of dining in a plastic bubble at a ski resort?" I'd email him.

"Are we still in takeout mode or is it OK to risk dine-in?"

With each COVID-19-related question, I worried, He must have better things to do — like keep people alive — than answer questions from a food reporter.

But Lahey always answered quickly, offering commonsense and informed advice in clear language. His answers considered the plight of restaurant workers as well as the power of pathogens.

Last winter, vaxxed and boosted, I decided to up the ante. I emailed Lahey to propose a profile of him and his wife, author and educator Jessica Lahey. They agreed. As the three of us arranged a time to meet, Lahey mentioned Zoom in his email. I preferred to talk in person and raised the possibility. I also posited by email that I didn't want to infect anyone with COVID-19, "least of all you."

We decided to meet at the Laheys' house in Charlotte. Each of us would take a rapid antigen test the hour before I was to arrive. I barely left the house the week before the interview.

That morning, Lahey alerted me that he and Jess had tested negative.

"Me too," I responded.

What I left out: I had tested myself twice in succession and was waiting for a third result.

It made sense at the time. After the first test, I thought it best to be super sure. So I took another. When the requisite 15 minutes had passed, I checked the second test under several different lights, looking for the telltale second line. It didn't appear, but I was overcome by a better-do-it-again internal imperative. Negative. Negative. Negative.

I grabbed a few pens and a couple of legal pads, found an unused mask, dumped it all on the passenger seat, and drove to Charlotte in a sleet storm. What's riskier, I wondered, driving on icy roads or transmitting probable nonexistent COVID-19 to an infectious disease doctor?

I realized on the way that I was thirsty. A dry mouth is not an optimal way to start an interview. But on the road to Charlotte, if you're past Shelburne, there's no water. I pulled over and ate snow.

At the Laheys' house, I put on my mask and knocked on the door. "You don't need to wear that," the mask-free expert told me. After 20 months of following Lahey's advice and passing it on to thousands of readers, I ignored him.