Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Trickle to Torrent: The Climate Crisis Brings Both Deluges and Droughts to Vermont

Published October 21, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 17, 2020 at 7:56 p.m.

On Halloween of 2019, an unexpectedly powerful storm system ripped through Vermont and northern New York, dumping up to five inches of rain, washing out roads and causing widespread power outages. According to the National Weather Service, record-breaking precipitation drove 10 rivers to surge to flood stage.

Less than a year later, 315,000 Vermonters, or half the state's population, are living under drought conditions. Creeks and streams have dried up, along with dozens of wells and natural springs across the state. As of last week, the water in Lake Champlain had receded to within two feet of its record low: 92.4 feet, set back in 1908.

“Fired Up” is a semi-regular series exploring Vermont’s climate-related challenges and what residents are trying at a local level to mitigate the planet’s heating trend — noting what’s catching on and what isn’t. We’ll also look at ways to become more resilient in the face of changes that may be inevitable.

Got a suggestion for the series? Send it to coordinator Elizabeth M. Seyler.

Though some rain has returned this fall, it hasn't been wet enough to pull Vermont out of its current water deficit. And the pouring-to-parched cycle tracks a troubling forecast for the state, according to Gillian Galford, a research associate professor who is heading the University of Vermont's 2020 climate assessment, a study that is due out next summer. When it comes to precipitation, Vermont's trend lines are moving steadily to the extremes.

Her team's report will provide state policy makers with the most up-to-date picture of how the climate crisis is affecting the state. Among its greatest emerging impacts, she said, are changing patterns of precipitation — too much, not enough or, occasionally, both in the space of months.

"We expect to see increasing precipitation, and it's not just increasing on average, in dribs and drabs spread out on every day of the year. It's increasing in extreme rainfall," Galford said. "But in between, we're going to have these prolonged dry spells. So that's a big challenge for Vermont going forward."

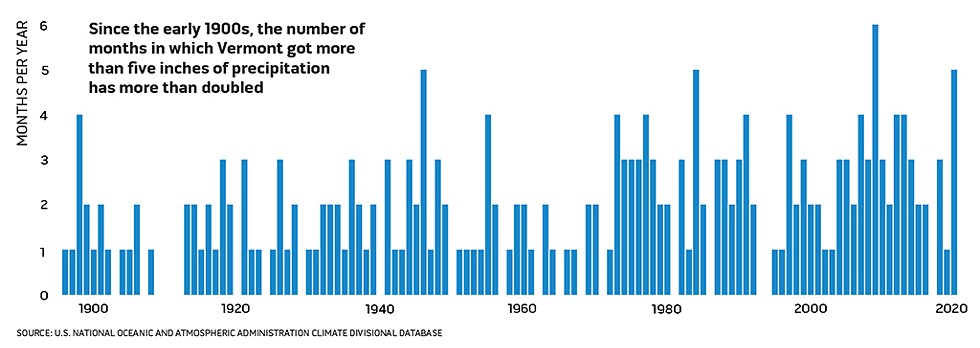

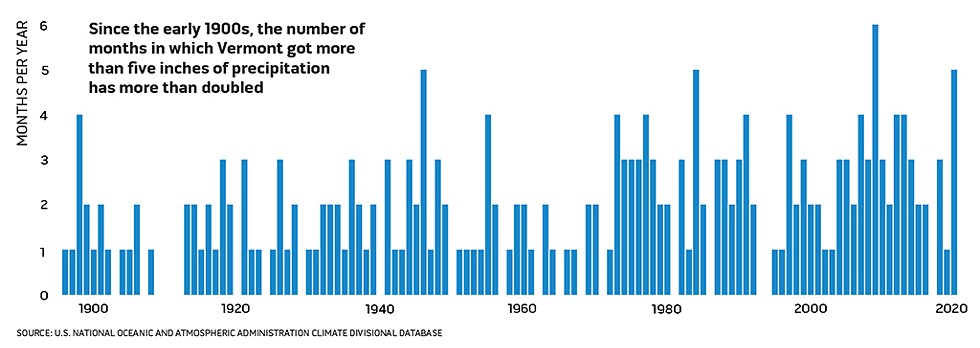

Indeed, annual precipitation in the state has risen by nearly seven inches in the past 50 years. Days with rainfall of an inch or more are twice as common as they were a century ago. Rain events of three inches or more are expected to happen twice every three years by the end of this century, an increase from the current rate of less than once per decade.

click to enlarge

- Source: U.S. National Oceanic And Atmospheric Administration Climate Divisional Database ©️ Seven Days

And that's not all.

"We're not going to turn into a California, but you're going to see seasonal droughts that extend across multiple years," said Chris Koliba, a professor in UVM's Department of Community Development and Applied Economics and, like Galford, a fellow at the university's Gund Institute for Environment.

The impacts on agriculture, forests, wildlife, tourism, public health and infrastructure are expected to be sweeping.

Just last week, officials asked for a federal emergency declaration, which would make Vermont eligible for aid. Farmers in 10 of the state's 14 counties have reported at least $27 million in crop losses from the ongoing drought. The forests around Killington were so dry this summer that a wildfire burned uncontrolled for more than a week underground as parched roots smoldered.

When the rain does come these days, it often overwhelms infrastructure intended to collect and clean it, washing runoff and partially treated wastewater into rivers and lakes. Heavy rains in 2019 triggered a landslide in the Mount Mansfield State Forest, sending acres of sediment into the Waterbury Reservoir.

Ski resorts that rely on snowmaking because Mother Nature doesn't reliably deliver suitable cover are spending millions to develop new water sources and storage capacity to expand snowmaking ability, raising concerns about watershed health.

But if there's an upside, Galford said, it's that Vermont learned many lessons about building resilience from Tropical Storm Irene in 2011. By taking steps to protect riparian zones and slow the flow of runoff into rivers and streams, she said, Vermont has been "flattening the curve" on the impacts of extreme weather events.

click to enlarge

- James Buck

- The exposed beach in front on the Burlington Surf Club on Lake Champlain

"In Vermont, we have a lot of natural infrastructure, so we can play to our strengths and use it to manage our water supplies," she said. "Some of those techniques that help us mitigate flooding can also help us retain water through these dry spells."

Time will tell what the climate crisis will mean for the Green Mountain State. Here is a look at some of the consequences of a water cycle increasingly driven to extremes — and how some Vermonters are attempting to adapt.

Well, Well

Davie Stoll stood far back from a reporter visiting his wooded Hinesburg property, but his social distancing wasn't motivated just by COVID-19. Stoll's well had run dry about a week earlier, and he hadn't bathed or done laundry since.

"When I start to smell, it's time to do something about it," he joked.

The solution — a water truck delivering 4,500 gallons — soon arrived. As the driver unspooled his hose, 61-year-old Stoll dragged it 400 feet through his backyard, into the woods and down a ravine to a decades-old concrete well. Removing the well cap, Stoll peered down into the nearly empty 20-foot hole, which he said had run dry only once before in 15 years.

Stoll dropped the nozzle in the well, then hollered to the driver. A gushing stream erupted. Essentially, Stoll paid $325 to pump water into the ground, in hopes that it would stay put long enough for him to use it.

"When this is all over," he said, "it'll be nice to take a hot shower."

Driver Steve Owen, owner of Fresh Water Haulers in Underhill, has been getting calls like Stoll's for months now. In non-COVID-19 times, Owen would have spent the summer providing drinking water for outdoor festivals and filling swimming pools and hot tubs.

This year, the deliveries to homeowners whose wells ran dry more than compensated for his pandemic losses. Since January alone, he estimated, he's pumped 3 million gallons, most of which he buys from the Champlain Water District.

"It's bad. We're hauling all day, every day," said Owen, who's owned the company since 2003. "I've seen this going on for about six years now. Every year it gets a little drier."

And not only private wells are running dry. Community water systems have tapped out their wells, taxing their infrastructure and their financial resources as they scramble for solutions.

Vermont has approximately 1,400 public water suppliers, of which about 400 are community systems that serve at least 25 year-round residents, explained Bryan Redmond, director of the state Department of Environmental Conservation's drinking water and groundwater protection division. Those 400 systems range from tiny ones that serve a handful of mobile home residents to the Champlain Water District, the state's largest, which pumps about 10 million gallons from Lake Champlain daily for 75,000 residents in northwestern Vermont.

This year, at least seven public systems have experienced supply problems, according to the DEC. One, in East Berkshire, started hauling water in from elsewhere in August and continued doing so through September. Another, in East Thetford, had to tap a new emergency well. To boost output from its two low-producing wells, Warren's South Village development is considering fracking, or injecting high-pressure water into the bedrock, a method akin to what's used in oil and gas extraction. "And I'm sure that's not the entire list," Redmond noted.

A decade ago, Redmond wouldn't have chalked up such problems to climate change. But after Irene caused widespread damage to public water systems, his division began rethinking how it plans for the dual challenges of floods and droughts. For example, all newly proposed public water sources must now demonstrate that they could endure at least a 180-day drought before the state will issue a permit.

But even if climate change weren't the issue, he said, Vermont still would be facing daunting challenges from its aging water systems. In 2018, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated that Vermont would need to invest more than $643 million in its public water infrastructure over the next 20 years to ensure public health and economic vitality.

"That's a staggering number," Redmond said. "But water infrastructure is buried, so for many people, it's out of sight and out of mind."

Tim Mills is utility director for the Town of Bethel, whose system pumps 65 million gallons annually to about 335 users, as well as downtown businesses. Bethel has fared OK through the drought thus far, "although we're keeping an eye on the [White] River," he said. "We've had some local residents whose wells have run dry. And I've never seen so many well trucks go through town."

In 2011, Irene's floodwaters washed out several of Bethel's water mains, destroyed wellheads and inundated pump stations, requiring replacement motors and new control units.

What does catastrophic flooding have to do with drought preparation?

"The big thing it's taught us is [planning for] capital repairs," Mills explained. After Irene, Bethel adopted an asset management system that the DEC promotes. It assigns a life expectancy to every piece of equipment, the cost of replacing it and a timetable to budget the work. Though such long-term fiscal planning might seem like a no-brainer, especially for a small water utility with a $249,000 annual budget, "you'd be surprised how many people don't grasp it," Mills said.

Bethel also took advantage of the state's free leak-detection service, which, Mills said, "paid off in spades." After finding a leak, Mills spent just $6,000 to replace 760 feet of water line. That repair reduced Bethel's water consumption by 200,000 gallons per month.

"This system has been let go for so long that it's not the water that costs me money," Mills said. "It's getting it to your house."

"It's been a super-popular program," Redmond added. In 2019, the state's leak-detection contractor surveyed 79 miles of pipe and identified 48 leaks, saving an estimated loss of 220,000 gallons of water per day — the equivalent of an Olympic-size swimming pool every three days.

As the climate crisis makes Vermont's summers and autumns hotter and drier, cost-effective conservation efforts such as this one can go a long way toward helping smaller water systems get through extended droughts.

In a state long perceived as water rich, the people who provide it cannot afford to take cheap and ample water for granted anymore.

— K.P.

Trout, Limited

When biologists from the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department hiked to the headwaters of Lewis Creek in late August, they weren't expecting to find it teeming with young trout. They knew the hot, dry summer had dropped water levels in streams across the state to near historic lows, and sporadic late summer rains had done little to boost flows.

Such conditions raise water temperatures, reducing the dissolved oxygen levels that cold-water-loving trout — brook, brown and rainbow, in particular — need to thrive.

Still, the Fish & Wildlife staffers were hopeful that the resilient species had found refuge in some of the cool pools that remained.

To conduct counts, biologists zap sections of creek with portable battery packs to briefly stun the fish. But it was they who were shocked by what they found — or didn't. In the same stretch where they'd counted 52 trout in 2013, this year they netted just six, said Will Eldridge, an aquatic habitat biologist.

"That is not good," he said.

The state's hatcheries, fed by creeks, were so low that Fish & Wildlife officials at one point considered taking the unusual step of stocking streams early — this fall instead of next spring. They were concerned that hatcheries couldn't support the fish until then.

The ground had been so parched in places that when rains did come — often in short, intense bursts — most of that precipitation ran off, failing to recharge groundwater, which, in turn, replenishes streams. As the water levels dropped, so too did the fish populations.

"Many, but not all, of the most productive streams in the state have very low numbers of trout," Eldridge said.

The apparent plunge in trout populations — more research is needed for confirmation — is connected to the drought, but it's not likely the only cause, according to Eldridge.

Last year's Halloween floodwaters may also have helped depress the trout populations. Such intense events can blast young fish right out of the headwater habitats that normally protect them.

If the pattern of intense precipitation events alternating with longer dry spells continues, as climatologists predict, some fish populations in the state could be at risk in the long term, said Louis Porter, commissioner of Fish & Wildlife.

"In the absence of measures that we can take to adapt to climate change, we may see rivers that historically held brook trout being unable to support them without stocking," Porter said.

If lower fish populations were to attract fewer anglers, that outcome would deliver an economic blow to the state. Sportfishing in Vermont is big business, drawing visitors from around the world to try their luck on the state's diverse waterways. Fishing and boating create $38 million in economic activity annually in Vermont, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. That doesn't account for the indirect benefits those visitors bring to the economy.

The state works hard to preserve and expand fish habitat, Porter said, by advocating for fish-friendly practices around hydroelectric dams, removing obsolete dams that are obstacles to fish, protecting river corridors from development through the Act 250 process and working with community groups to restore fisheries.

Using federal funds, the state is doing more such projects, according to Porter. He pointed to the acquisition earlier this year of the flood-prone Fitzgerald farm on the Winooski River in Colchester. An effort is now under way to restore the property to wetlands, he said.

Lewis Creek's habitat challenges are not unique, but they are noteworthy because they persist despite tireless work by one of the most active watershed restoration groups in the state.

The Lewis Creek Association has for decades tracked and worked to improve the water quality along the creek's 80-mile run from the Green Mountains east of Starksboro through forests and farmland to where it empties into Lake Champlain in North Ferrisburgh.

"The diversity of habitat types is unbelievable," said Marty Illick, executive director of the association. "It makes me shiver to think what richness we have here."

The group's volunteers have planted trees near the creek's banks to cool its waters, installed places for fish to find refuge, and advocated for buffer zones and places where the creek can naturally meander, she said.

Land-use patterns — including the development of farms, homes and roads right up to riverbanks — have tended to channelize, or hem in, Lewis Creek and many other waterways in the state, she said.

This exacerbates the sluicing effect in major storms, sending water racing down the channel, eroding banks and giving the waterway no chance to spread out, release the sediment and pollutants it carries, and seep into the ground to recharge the water table.

"We need to keep the rainfall in our watershed. Period," Illick said. "If we don't do that, whether it's drought or flood, we're going to compromise the environmental health of our state."

She worries, however, that the state isn't moving quickly enough to help natural areas weather the stresses of a changing climate.

"It's excruciatingly painful to see how slow our state's leaders and local people are in understanding the situation," she said.

— K.M.

Cyanobacteria Likes It Hot

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of University Of Vermont Spatial Analysis Laboratory

- Cyanobacteria in Burlington's Oakledge Park on September 3, 2020

More extreme precipitation spawns more of what the Gund Institute's Galford called "flashy," or fast-moving, water. Rapid stormwater runoff can overwhelm sewage treatment plants, wash out roads and culverts, and sweep tons of nitrogen- and phosphorus-laden sediment into streams, rivers and lakes.

Combine those nutrients with warmer water temperatures — parts of Lake Champlain have risen, on average, by seven degrees since 1964 — and the result is an ideal environment for cyanobacteria blooms.

Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, is more than just a yucky mess that closes beaches, drives away boaters and makes swimming undesirable. It's also a public health hazard. In 2014, Toledo, Ohio, warned more than 450,000 residents to stop drinking tap water due to a bloom near the city's water intake system on Lake Erie.

The Champlain Water District draws its water from Shelburne Bay. According to general manager Joe Duncan, the district's intake pipes are located half a mile offshore and 80 feet down. At that depth, the thermocline — or steep temperature gradient between the colder water below and warmer surface layer — prevents cyanobacteria from infiltrating the water supply.

Duncan said that he considers the thermocline one of the system's most important protective barriers; to date, cyanobacteria hasn't shown up in the drinking water. But as Vermont's winters get shorter and warmer, he added, "climate change has really wreaked havoc on it over time."

People needn't drink cyanobacteria to get sick from it; even touching it can cause allergy- or flu-like symptoms. Some preliminary research even suggests that people who live near lakes where cyanobacteria blooms can inhale its aerosolized toxins and develop neurological problems.

Cyanobacteria first gained public attention in Vermont in the 1990s when two dogs died after swimming in Lake Champlain. Humans exposed to it can develop sore throats and runny noses, as well as dizziness, numb lips and tingling in their extremities. In more severe cases, cyanobacteria can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting and even liver damage.

Currently, the state doesn't track illnesses associated with cyanobacteria, largely because it's so difficult to pinpoint their origins, according to Vermont Department of Health toxicologist Sarah Vose. Nevertheless, cyanobacteria is becoming a wider public health concern.

"Due to climate change we are seeing, unfortunately, a greater frequency of blooms over time," said Lori Fisher, executive director of the Lake Champlain Committee, a bistate citizens' organization dedicated to the health of the lake.

In 2003, the committee launched a community-based cyanobacteria-monitoring program in collaboration with state environmental and public health agencies. From spring through fall, it recruits and trains volunteers, who routinely monitor more than 100 locations on Lake Champlain.

When monitoring began in 2003, volunteers didn't start looking for cyanobacteria until late June and generally ended their season by Labor Day, when most beaches closed, Fisher said. Last year, its volunteers were out looking from mid-June through mid-November.

Cyanobacteria is easily identifiable, Fisher noted, but the only way to know for sure whether it's producing toxins is through laboratory analyses. Years ago, it took a week or more to notify the public, by which time, Fisher said, lake conditions often had changed.

Today, teams of Lake Champlain Committee volunteers issue warnings within hours of bloom sightings, get signs erected on beaches, and post alerts on the state's online Cyanobacteria Tracker Map. The committee also sends out weekly email blasts to educate the public on recreating safely on Lake Champlain and other cyanobacteria hot spots, such as Shelburne Pond and Lake Carmi.

Some Vermonters, such as Glynda McKinnon of Vergennes, won't swim in Lake Champlain anymore because of the bacteria.

In March 2014, McKinnon began noticing that her life partner, Dave Scheuer, was slurring his words. At the time, the 62-year-old real estate developer seemed otherwise healthy. A U.S. Olympic Team skier in the 1970s, Scheuer was active and outdoorsy, McKinnon said, a "big personality" who enjoyed telling stories, riding horses and sailing on Lake Champlain.

In September 2014, following months of neurological tests, Scheuer was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease. The day of his diagnosis, he and McKinnon went boating on Lake Champlain.

It would be among Scheuer's last trips on the lake. Scheuer's ALS progressed rapidly until August 6, 2015, when he used Vermont's death-with-dignity law to end his life at age 63.

After Scheuer's death, McKinnon grew curious about research being done by Scheuer's neurologist, Dr. Elijah Stommel, at Dartmouth-Hitchcock medical center. His study of ALS clusters around New Hampshire's Lake Mascoma suggested a possible correlation between cyanobacteria and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and ALS. Of particular concern is the potential for neurotoxins to become aerosolized in water droplets, which then can be inhaled.

In 2016, McKinnon attended an event at All Souls Interfaith Gathering in Shelburne, where she met the couple who'd bought Scheuer's former lakefront home. They mentioned that their groundskeeper, Jim Glabicky of Jay, had also been diagnosed with ALS. Like Scheuer, Glabicky was an avid skier and snowboarder who often swam in Lake Champlain after work. Glabicky died of ALS in August 2017 at the age of 52. The potential link was impossible for McKinnon to ignore.

McKinnon later joined the board of the Lewis Creek Association. Scheuer's death, she said, gave her environmental advocacy work new urgency.

"I describe my role as being at the end of the pipeline," she said. "I'm not a scientist. I don't know a ton about water issues. But at the end of the pipeline is our health."

To date, any causal link between cyanobacteria and neurodegenerative diseases is tenuous and unproven, according to the health department's Vose. But even if the science never bears out a connection, she said, there are still many reasons to be concerned about cyanobacteria exposure.

Which are the most worrisome bodies of water for cyanobacteria? Vose said it depends how you define it.

"The most problematic location," she said, "would be anyplace where Vermonters are not aware of the risks ... and how to protect themselves."

— K.P.

Stir Fried

Erik Andrus is not your typical Vermont farmer. That was apparent as he drove his Japanese rice combine through a weed-choked rice paddy earlier this month — wearing a beret.

But this summer, Andrus, who grows a type of Japanese rice prized by gourmet chefs, shared common, parched ground with many of those who struggled to coax reluctant crops from the earth. Soon after planting seedlings in five flooded acres in Ferrisburgh in May, his miscalculation became painfully clear.

"I quickly realized we weren't going to have the water to sustain that much acreage," said Andrus earlier this month beside a field of crisp brown husks of dead rice plants and weeds.

To grow rice, fields must be inundated with water deep enough to suppress weeds. It's one of the most water-intensive forms of agriculture in the world.

Having sufficient water had rarely been a problem for Andrus. The low-lying fields of his Boundbrook Farm abut a tributary of Little Otter Creek. After rains, his 1.1 million-gallon irrigation pond normally fills to the brim in short order.

But the lack of spring rain meant there was no runoff, and by June the pond was reduced to a shallow, mucky mess.

"In the 10 years we've been doing rice, we've never had a year this bad," Andrus said.

To conserve the little water that remained, he stopped irrigating one acre. Then another. Then a third, hoping to salvage at least two acres of rice.

"In retrospect, we should have given up on all but one," he said.

The rice in the abandoned fields quickly dried up and died. The water wasn't deep enough in the two remaining acres to suppress the weeds, which quickly took over. He's harvested about a tenth of what he expected.

"It sucks. It's just been such a shitty year," Andrus said.

The only upside has been that his flock of 600 domestic ducks, which he raises in the flooded fields, fattened up nicely, and he was able to sell them in Canada for a handsome profit.

He remains undaunted by his crop losses, however, and is determined to press forward: Andrus is expanding to rented land in a new location two miles away along a larger creek.

The drought has been challenging for many kinds of farmers this year, said Alyson Eastman, deputy secretary of the state Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets.

The agency warned in August that the sporadic rainfall had provided little drought relief for the region, and a disaster declaration was in the works. If approved by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the declaration could provide farmers who lost crops emergency loans and price supports.

A photo released by the state agriculture department this summer showed a field of hemp plants in soil so dry it had cracked open. As bad as it has been, Eastman said, the difficult season has also brought out the resourcefulness of the state's agricultural industry.

"It's amazing to see how farmers are adjusting," Eastman said.

Many have embraced soil conservation, not only to reduce runoff that can pollute waterways but also to improve soil resiliency and crop yields, Eastman said. Use of no-till planting methods and cover crops improves soil health and makes the land better able to absorb rain — and therefore more climate resilient, she said.

Such techniques allowed farmers who lost one crop to drought this year to pivot to plant others when conditions improved, something that traditionally hasn't been possible.

Orwell dairyman Jonathan Lucas said he has been working his tail off to adopt the best field management practices.

"The weather we've had in Vermont in the past couple of years, it's been feast or famine — it never stops raining or it never rains at all," said Lucas, who's been raising dairy cows for almost a decade.

That makes it tough to grow enough feed for his 280 milking cows. This year, his hay crop was inconsistent, and about 90 acres of corn never got the rain it needed to take off, he said. He was forced to purchase feed from a failed neighboring farm.

After a welcome August rain, Lucas decided to try to harvest something off the property, so he planted two feed crops he'd never tried before — soy and sorghum.

The yields haven't been much to speak of, but every little bit helps keep feed costs in check and his dairy farm afloat during a time of depressed milk prices.

"It seems we're having to try something different every year," Lucas said.

— K.M.

Climate Controlled

On a very different farm about an hour and a half northeast of Orwell, an early October thunderstorm unleashed a downpour furious even for the Mad River Valley. Dave Hartshorn and John Farr, surrounded by a sea of delicate green produce, looked heavenward, marveling at the intensity of the sudden deluge.

"Whoa, it's really coming down now!" Farr declared over the percussive din of raindrops pelting their Waitsfield farm.

Instead of scrambling to salvage their valuable vegetables, however, the men strolled calmly down neat crop rows as the torrent harmlessly drummed the greenhouse roof above.

As farmers across Vermont struggle to adapt to an increasingly unpredictable water cycle, more may be forced to seek shelter from extreme weather events by growing crops indoors.

"I think it's going to get uglier before it gets better," Farr said. "If the climate changes to the point where you can't grow crops outside, this is the answer."

"This" was thousands of tender lettuce, basil and watercress plants — from trays of pea-size sprouts to lush, leafy greens ready to fetch top-dollar in the Whole Foods produce aisle — protected from the elements raging on the other side of just a few millimeters of plastic.

"This is climate change," Hartshorn said. "To do what we do, we've had to change the climate."

When it's snowing outside, the pampered, hydroponically grown plants bask in a near-constant 72 degrees. At night they soak up the rays from violet-hued LED lamps. When the summer sun threatens to scorch their delicate foliage, a high-tech shade cloth shields them. And no matter how much — or how little — rain the valley receives, they drink from a steady stream of nutrient-rich recycled well water.

When Irene slammed the state in August 2011, Hartshorn watched helplessly as floodwaters inundated his fields along the Mad River at the peak of the growing season.

So when he and his partners went looking for a place to locate an experimental hydroponic farm, they made sure to build Green Mountain Harvest Hydroponic's greenhouses well outside of the expansive floodplain. They chose a spot uphill from Hartshorn's popular farmstand, which is a major tourist draw in the Mad River Valley.

They opened in 2013 after an investment Farr admits would be cost-prohibitive for many farmers. The Hartshorn and Farr families own hundreds of acres of agricultural land combined and were able to leverage those acres to raise the money needed to get the new operation off the ground.

Finding a way to expand the growing season to year-round in Vermont seemed like a great idea, but it has been a struggle, Farr said.

Raising vegetables hydroponically — in water instead of soil — isn't that hard, but doing it profitably is. They've tried more than 15 crops to date, including kale, cilantro and parsley, before landing on the basil, watercress and summer crisp leaf lettuce.

Energy costs can be significant, a major reason the model might not pencil out in other places, Farr said. The LED and high-pressure sodium grow lights are highly efficient, but running them several hours a day all year would still do a number on their electric bill if it weren't for their 100kW solar array. Low natural gas prices keep heating costs manageable, but if that changes, they can switch to a backup biomass boiler.

And keeping the place cool in summer — especially a hot one like this year's — requires a two-pronged approach. A retractable shade curtain infused with aluminum strips reflects sunlight, and an evaporative cooling system keeps the temperature in check, if needed.

For water, a 475-foot-deep well draws 22 gallons per minute, more than enough for the half-acre operation. The water is mixed with fertilizer and delivered in a gravity-fed system to the base of the plants growing in row after row of containers that resemble waist-high rain gutters.

The combination of natural and artificial light, steady warmth, and a regular, nutrient-rich water supply mean the crops grow phenomenally quickly. The lettuce is ready to harvest in 30 days, so they get 12 crops a year. The basil grows even faster, yielding 14 crops annually. The superstar is the watercress, a water-sucking superfood ready to harvest 25 to 30 times per year.

They estimate that the ability to grow year-round and in ideal conditions gives their little greenhouse the productivity of a conventional 200-acre Vermont farm.

In addition to growing faster and in a cleaner environment, the greens are sweeter and more tender than the more fibrous field-grown versions, Hartshorn said.

The venture was hatched mostly to grow crops year-round in a more sustainable, efficient way. But Hartshorn said it has proven an important way to diversify a flood-prone farm, making it more resilient to the impacts of the climate crisis.

"I know that some of the land that I'm farming now," he said, "will not be farmable when the big one comes."

— K.M.

Correction, October 26, 2020: An earlier version of this story misidentified the location of a community water system that is experiencing supply issue. South Village in Warren is considering fracking its wells.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Trickle to Torrent | The climate crisis brings both deluges and droughts to Vermont"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Authors

Kevin McCallum

Bio:

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Latest in Environment

Speaking of...

-

Vermont Senate Advances Bill to Make Big Oil Pay for Climate Crisis

Apr 2, 2024 -

Court Upholds Vermont Gas' Purchase of Methane From a New York Landfill

Jan 12, 2024 -

Vermont Lawmakers May Have to Meet Growing Problems With a Shrinking Budget in 2024

Dec 20, 2023 -

Key Vote on Burlington District Energy Project Looms on Monday

Nov 17, 2023 -

UVM Scientists Unearth Bad News for Our Climate Future Beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet

Oct 11, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: