Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

UVM Cancels Commencement Speaker Amid Pro-Palestinian Protest

-

Education

Education Bill Would Speed up Secretary Search…

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

- Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News 0

- 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis 0

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Published July 26, 2023 at 10:00 a.m.

As the rain poured down on July 10, Ashley Sorrentino kept an eye on her recently planted cannabis crop with surveillance cameras. She was safe and dry at home in Essex, but her greenhouse of 315 plants sat in a field next to the rising Lamoille River in Johnson.

She could see just a couple inches of water at first. "And then, not even 20 minutes later, six feet of water — raging river water," Sorrentino recalled. "It was gnarly. We thought everything was gone."

Once the river receded, Sorrentino was surprised to see that most of the plants at Stormy Acre Farms were still standing. That gives her hope she can save some of her crop. Unlike fruits and vegetables, which must be destroyed if they have been flooded, cannabis that has yet to bud can sometimes be salvaged, according to Cary Giguere, compliance director for the Vermont Cannabis Control Board, which regulates the marketplace.

"In a lot of instances for our growers, we're early enough in the season where the usable portion of that plant hasn't been produced yet," Giguere said. "We don't even have plants that are pre-flowering yet."

Sorrentino's weed, like any cannabis product, will be tested for pathogens, mold and heavy metals before it's cleared to be sold. She also plans to test the soil.

"Obviously, if it comes down contaminated, we're really screwed," Sorrentino said.

Two weeks after historic flooding swamped Vermont, the state's cannabis industry is still taking stock of the damage. While total losses have yet to be calculated — and might not be known until the fall harvest — the deluge hit every part of the marketplace, from small and large growers with riverside fields to manufacturers and retailers in flooded cities and towns.

"For some people,

there are no options — this year is just

a wash for them." James Pepper tweet this

The crop damage is unlikely to create a supply crisis, but the natural disaster struck at a pivotal moment for the fledgling cannabis industry. Shops only opened last October, and entrepreneurs have begun renewing their licenses for year two of the legal market. The Cannabis Control Board has licensed more than 515 businesses and announced on July 19 that some 1,100 people in the state work in the industry. Through May, consumers had bought nearly $50 million worth of Vermont cannabis products, and the state had raked in about $7 million in excise taxes, according to tax department data.

But because the plant is illegal under federal law, cannapreneurs won't be eligible for loans or grants from the U.S. Small Business Administration or the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Farm Service Agency. Without cash support to cover losses, some businesses could fold, according to James Pepper, chair of the control board.

"It's just brutal," he said. "For some people, there are no options — this year is just a wash for them. There's no crop insurance. There are no magic funds to help them."

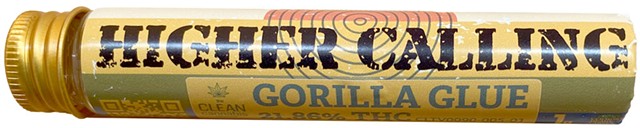

click to enlarge

- Sasha Goldstein ©️ Seven Days

- Proceeds from this pre-rolled joint go to a fund that will benefit flood-damaged businesses

Industry advocates are dreaming up other ways to raise cash to keep weed businesses afloat. One fundraiser will be hitting the shelves in cannabis stores soon: a Higher Calling pre-rolled joint, with proceeds going to a fund that will benefit flood-damaged businesses, according to Todd Bailey, executive director of the Cannabis Retailers Association of Vermont. He thinks the total losses could be in the tens of millions of dollars.

Bailey said his trade group is also working on a two-day benefit concert to be held in Cabot in September. The 80-member Vermont Growers Association, another trade group, was planning a mixer at Deep City in Burlington on Wednesday, July 26. Cofounder and executive director Geoffrey Pizzutillo said the group planned to use the event to launch the Vermont Cannabis Industry Emergency Fund, which would raise money for grants now and ideally come up with enough to help out in future disasters.

More traditional, state-level financial help is possible, too. The control board has gotten more than 150 responses to a survey of all licensees, who were encouraged to report any damages. Pepper wants to aggregate the data and report it to the legislature in hopes of receiving some relief for those in the industry; the Vermont Growers Association has similar plans.

"The cannabis community is abuzz with ideas right now," Pepper said. Assessing the storm's impact on the nascent industry is currently the board's No. 1 concern, he said.

Affected growers and sellers might also get relief from the Vermont Main Street Flood Recovery Fund, a statewide effort that has raised some $300,000. Bailey, who serves on the board overseeing the fund, said cannabis businesses — just like any others — are eligible to apply. Grants of $2,500 are available now, though the board hopes to have enough eventually to give businesses up to $10,000.

"We're thinking specifically and strategically about women-owned businesses, businesses owned by the BIPOC community, new Americans," Bailey said. "Some of those communities aren't as well connected to resources as others, and so we're trying to both be quick and help people right away, but also thoughtful so that we can help as many people as possible down the road."

The most publicly visible damage to a weed business was in downtown Montpelier, where retailer Capital Cannabis has been forced to close indefinitely. The Main Street store took in two or three feet of water when the Winooski River swamped the city. But just as owner Lauren Andrews prepared to reopen, a pipe burst upstairs, causing catastrophic damage.

"We lost a week of work, and then it was all ruined," Andrews recalled. "That just broke our hearts." A sister CBD store she runs next door, AroMed Essentials, was also badly damaged.

At Capital Cannabis, Andrews was able to ameliorate the flood's impact. Before the storm hit, she got a waiver from the state to move her product out of the store, allowing her to salvage about 90 percent of what she had in stock. And she's already found a new space, at the Berlin Mall, where she plans to reopen temporarily this week. She doesn't expect to lay off any employees, and, ultimately, she wants to be back at her Montpelier shop, which she opened last November.

"It's been the most difficult time of my life," Andrews said. "I feel fortunate in some ways, though, because so many people have lost their homes."

click to enlarge

- Sasha Goldstein ©️ Seven Days

- Lauren Andrews (center), Todd Bailey (right) and Jesse McFarlin (far right) on Tuesday

At a press conference on Tuesday outside Andrews' gutted shop, she, Bailey and others in the industry gathered to bring attention to fundraising efforts. Andrews estimated she's lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in product, lost revenue and reconstruction costs. Jesse McFarlin, an outdoor grower in Danville, said her company, Old Growth Vermont, lost a field of plants that would have been worth some $200,000. And Dusty Kenney, owner of Cambridge Cannabis Company, said damage to his new grow room could cost north of $100,000 to repair.

"We keep talking about 'We're Vermont strong or 'We're still Vermont strong,'" Andrews said, becoming emotional. "We can say these words, but the reality is that being strong all the time through something like this is — it's exhausting. It's overwhelming." The silver lining, she said, was the outpouring of support from staff, the local community and people in the weed biz.

Vermont has cultivated a cannabis industry of small craft growers, and those entrepreneurs might lose the most. Pepper, the control board chair, said one grower not only lost all of his plants but also sustained damage to his field, meaning he won't be able to replant. The grower plans to raise a few plants in buckets and hopes for a harvest of some 15 pounds — compared to the 300-pound crop he expected, Pepper said. The grower pays $5,500 annually for his license.

"Is he going to be interested in renewing [his license] next year? Is he going to have the money to renew next year?" Pepper said. "I don't know."

The grower in question, Sean Trombly, said he'll survive the flood; he also grows indoors, which sustains his business, Trombly House of Cannabis. But he'll take precautions — such as building greenhouses or installing drainage pipes — next season to protect himself from heavy rain, which cost him 625 plants this year.

"Outdoor [growing], to me, is just very unpredictable," Trombly said. "This is a perfect example."

Other growers are already contending with mold and other pathogens that could stunt yields down the line, according to Pizzutillo of the Vermont Growers Association.

"We are sort of beginning to see some early signs of these later-season diseases, and we're not even halfway into the season yet," he said.

Back in Johnson, Sorrentino considers herself lucky that things weren't worse. She lost 15 percent of her crop and spent time and money cleaning up and buying new tools and supplies. But her greenhouse remained structurally sound, and she also has a cannabis dispensary in St. Albans, MothaPlant, that was untouched by the storm. She'll wait and see whether her remaining plants survive — and hope for the best.

She noted the irony of her farm, Stormy Acre, being flooded just weeks after she planted. Maybe, she mused, the name will "bring us some good luck and get all the disasters out of the way now — and the rest of the year will be easy-peasy."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Flower Outage | With no federal lifeline, cannabis businesses count their flood losses"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize' Vermont’s Weed Culture

Apr 17, 2024 -

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host State's First Weed 'Farmers Market'

Mar 20, 2024 -

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

Mar 8, 2024 -

After 15 Years and Two Major Floods, Montpelier’s Three Penny Taproom Is Thriving

Jan 30, 2024 -

A Donation to Montpelier's Public Library Repays a Favor From 95 Years Before

Jan 24, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 2. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 3. Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down in December News

- 4. Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State

- 5. UVM Cancels Commencement Speaker Amid Pro-Palestinian Protest News

- 6. Education Bill Would Speed up Secretary Search Process Education

- 7. Help Seven Days Report on Rural Vermont 7D Promo

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis