Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Life Stories: Oda Hubbard 'Felt Strongly About Her History'

Published April 13, 2022 at 10:00 a.m.

Thousands of daffodils will bloom next month at a highway visitor center in southern Vermont. The flowers are a living memorial to people who died on 9/11.

When about 35 volunteers gathered at the Guilford Welcome Center for the planting in October 2001, the question arose: How do you plant 5,000 daffodil bulbs? Phyllis Austin of Shelburne, who spearheaded the daffodil project, turned to her friend Oda Hubbard (August 17, 1925-February 3, 2022 ) for the answer.

"'Everybody take a handful of bulbs and throw them up in the air,'" Oda advised, as Austin recalled. "'Wherever they land, that's where they should be.'"

In an instant, what might've been a daunting gardening project became fun and doable. The method also reflected Oda's gift for beautiful, natural design. Every spring, the daffodils brighten and enliven the place that welcomes visitors and Vermonters to the state at its southern border.

Oda was a visitor when she arrived in this country in 1946, a 21-year-old traveling on a tourist visa from the Netherlands. She was a Vermonter when she died on February 3 at age 96, holding the hand of her daughter Alice Hubbard Lissarrague.

Oda had lived for 61 years in Shelburne, where she and her late husband, Charlie, raised their four children in a concrete house he designed. Her aesthetic, which Charlie shared, defined the home: European antiques and midcentury modern; an Eames chair and an oriental rug; sparse décor, treasured artwork and vibrant flower gardens.

Oda Waller was born on August 17, 1925, in Hilversum, Netherlands. Her father, Jacob Marinus Waller, was a Dutch engineer who worked in the oil business. As a college student, he and a friend built a car in the attic of his Amsterdam home and lowered it to the street for a road trip around Europe. Her mother, Caroline Warner Schoverling, was an American from New Milford, Conn.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- Oda Waller (left), age 2, and her sister, Hannah, in traditional Dutch attire

Jacob and Caroline met on an ocean liner sailing from Rotterdam, Netherlands, to New York City. She was returning home after visiting relatives in Germany; he was headed to the U.S. for work. They were engaged by the time the ship docked in the states and married soon after.

Oda's older sister, Hannah, was born in California before the family settled in the Netherlands, where Oda was born. She grew up speaking English and Dutch — as well as German, spoken by the household help. (Oda was still reading books in German and singing Dutch patriotic songs at the time of her death.)

Oda was 14 when the Nazis invaded her homeland in May 1940; her family's life was profoundly changed. For a short time, Nazi soldiers occupied the Wallers' house. During World War II — which Oda called, simply, "the war" — she and her family (like their fellow countrymen) faced hunger. On occasion, they resorted to eating tulip bulbs.

Oda bicycled to a farm to trade household goods — baby clothes, linens, gold pieces — for food. Yet because her mother was American, and the U.S. had not yet entered the war, Oda and her family experienced less deprivation and hardship than their relatives and neighbors, according to her youngest child, Jonathan.

"She didn't go to the labor camps, like other people who were sent off to Germany and suffered terribly," Jonathan said. Now 56, he remembers his mother taking him to Ottawa when he was a boy to see the flower gardens on the parliament grounds, planted in tribute to Canada for its role in liberating the Netherlands. "She made sure I saw that," Jonathan recalled.

After the war, the family immigrated to the United States, where they stayed for a time with Oda's aunt in Rye, N.Y. When her aunt served sandwiches on white bread, Oda told her that she "didn't have to get out the fancy bread for us," Jonathan said, recounting a story his mother had told him. Oda hadn't eaten white bread for six years.

In Holland, Oda had studied horticulture. She pursued that field as a landscape architecture student at Harvard University's Graduate School of Design. But she transferred to Harvard's architecture program, where she met Charlie Hubbard, her future husband. Though she stopped her graduate work short of a degree, Oda remained interested and engaged in design and architecture throughout her life.

In the 1950s, the Hubbards moved to Vermont, where Charlie established his architecture career and the family settled in Shelburne. The couple purchased Maeck Farm, which had roughly 300 acres, and built their home there. They kept their land in agriculture, first in dairy and then Charolais beef cattle imported from France. Alice believes theirs was the first herd of that breed in Vermont.

Oda was a strong proponent of progressive education, and her involvement in local schools included being a founding parent of the Schoolhouse learning center. She also volunteered at the Charlotte Pony Club, where her kids rode horses.

"She was very down-to-earth," Alice said of Oda's approach to motherhood. "The whole point was to be outside and use our imaginations. You didn't need to be entertained."

Oda and Charlie were committed to land conservation and donated farmland to the Vermont Land Trust. The Hubbards gave 186 acres in Shelburne to the nonprofit land conservation organization, according to the land trust.

"She thought it was important to preserve land and be a custodian of land," Jonathan said. Oda believed that conserving land was simply "the right thing to do," Alice noted.

The trust later sold the land, with a conservation easement, to a farmer. "These early transactions were very important in building understanding and rapport in the farm community," said Darby Bradley, past president of the trust.

In 1989, Charlie died of cancer at the age of 67. Oda stayed in their home another dozen years before moving to a condominium in the Gables at Shelburne.

Oda was actively involved in community and family life and lent her design sense and distinct aesthetic to civic endeavors and the projects of friends and relations. She served for more than two decades on the Shelburne Historic Preservation & Design Review Commission, to which she brought a "wonderful sense of humor and bright eyes," said chair Fritz Horton, a retired architect. He noted, as well, that "she did speak her mind."

"With Oda there, I think applicants felt there was a wise person sitting across the table," Horton said.

In another volunteer role, Oda decorated Shelburne Museum for special events and occasions. Her knowledge of the collection and strong, steady work ethic made Oda a "real prize" for the museum, said her friend and fellow volunteer Barbara Heilman.

"She was the volunteer extraordinaire," Heilman, 81, said. "Everyone turned to her because she had such exquisite taste and was so well-read and so interested in history. She was really a go-to person."

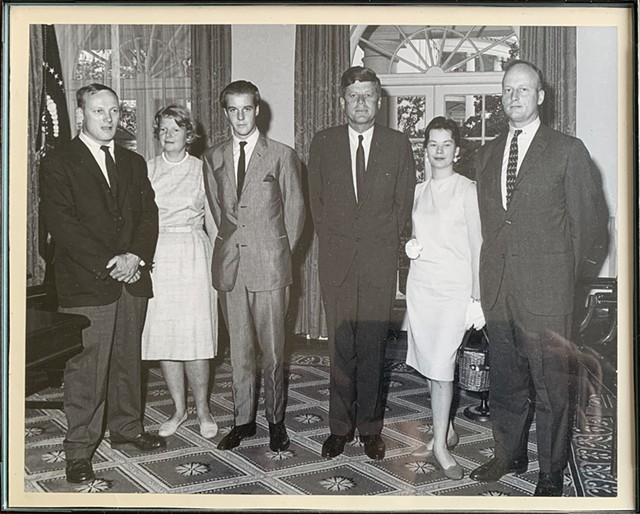

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- Oda Hubbard (second from left) at the White House with president John F. Kennedy in 1963, as part of a bicentennial celebration for Shelburne

Oda made the floral arrangements at Christophe's on the Green, the acclaimed French restaurant in Vergennes that Alice and Alice's husband, chef Christophe Lissarrague, owned and operated.

When Oda's friend Sally Wadhams sought her advice on purchasing a house, Wadhams was adamant about one thing: no raised ranch. Yet for 30 years Wadhams has lived happily in the Shelburne raised ranch Oda recommended she buy. Oda saw past the genre to appreciate the home's lines, light and good bones.

For 30 years, the friends engaged in conversation that was "always interesting, always smart," Wadhams, 69, said. "We picked up the thread wherever we were."

The two friends drove around Vermont, sometimes traveling back roads, to attend estate auctions and museums. Oda was a wonderful listener and a first-rate observer, Wadhams said. She might comment on the shape of her soup bowl as they ate lunch in a restaurant or the pitch of a farmhouse roof viewed from the car window.

In 2006, their conversation was recorded for StoryCorps, a nonprofit that has recorded and preserved the oral histories of more than half a million people since 2003. Wadhams interviewed Oda in a mobile studio on Church Street in Burlington.

"Oda felt strongly about her history," Wadhams said. "She always involved her children in that: knowing who their family was, who their relatives are and what their background is."

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Life Stories, Oda Hubbard

More By This Author

About The Author

Sally Pollak

Bio:

Sally Pollak is a staff writer at Seven Days. Her first newspaper job was compiling horse racing results at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Sally Pollak is a staff writer at Seven Days. Her first newspaper job was compiling horse racing results at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Video: A Ford Model A Named Lizzie Has Been Driven by the Aubin Family for Five Generations Stuck in Vermont

- 2. Bristol Journalist Alex Belth Compiled an Anthology of Classic Celebrity Profiles From the 1960s and ’70s Books

- 3. Book Review: 'The Cemetery of Untold Stories,' Julia Alvarez Books

- 4. Award-Winning FaMa Quartet Reunites to Fête the Green Mountain Chamber Music Festival Performing Arts

- 5. At the Phoenix Gallery, the Group Show “Flora” Is Like a Field of Wildflowers Art Review

- 6. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, May 15-21 Magnificent 7

- 7. Q&A: At the Lanpher Memorial Library in Hyde Park, a "Wind Phone" Connects Callers With Lost Loved Ones Stuck in Vermont

- 1. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 2. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 3. Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate Poetry

- 4. Monsignor John McDermott Named Bishop of Burlington Books

- 5. Animal Communicator Amy Wild Wants a Word With Your Pet Animals

- 6. Two Performances Highlight a Nearly Forgotten Viennese Composer With Vermont Ties Performing Arts

- 7. STRUT! Fashion Show Returns After Four-Year Hiatus Culture