Published December 3, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

Hugo Martínez Cazón discovered a winding, ancient Vermont sewer. When he followed it, he uncovered nothing less than the American origins of two winter sports and the secret geography of the state's largest city.

But let's back up a bit.

An environmental cleanup engineer, Martínez Cazón, 57, found his true passion in old maps and historical documents. He's been a "map geek" since he was a kid, but a more apt description is "historian." When just a teenager, he realized that maps lay out their data in three dimensions: height, width and time. Maps of a single place from different eras rarely line up. As Martínez Cazón says, "All those lines that your teacher told you, 'These are the lines that tell you what Germany is' — they're gone. They're just lines."

Like all good historians, Martínez Cazón knows that seemingly dry primary-source documents are often the key to historical revelation. By poring over old maps, census figures and insurance reports, he's determined that, until the late 19th century, a deep, wide ravine containing a sewer used to snake its way right through downtown Burlington.

Martínez Cazón's sojourn through that sewer was, in two ways, a virtual trip. First, neither the sewer nor the ravine are still around. Second, he's mostly used digital tools such as Google Earth to piece together evidence for this now-forgotten gully. But to hear him talk about his labor of love — and to watch as he unlocks new layers in his digital map (he likens it to lasagna) — is to witness the unfolding of a convincing historical argument.

Martínez Cazón has lived in Burlington since 1990, at one point residing on Hyde Street in the city's Old North End. Curious about his peculiarly shaped backyard, he started asking around. The most useful clue came from a neighbor, an elderly woman named Bea, who said that the yard's unusual boundaries were drawn to accommodate a railroad line.

His curiosity further piqued, Martínez Cazón turned to a collection of 19th-century Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, some of which contained surveyors' reports that refer to 15-foot-high embankments. The neighborhood's present-day terrain, though, is level. So where were these alleged embankments? And did they have something to do with the railroad?

Martínez Cazón eventually pieced together that "Bea's railroad" did indeed run through this ravine in the 1850s; its path wound from Isham Street through the southwest corner of the central downtown grid, then into Lake Champlain around Adams Street (which, before the shoreline was extended, used to run to the lake).

Martínez Cazón's hypothesis is that, in the mid-19th century, the ravine railroad was the path of least resistance for hauling plank wood from Winooski mills to cargo boats on Lake Champlain. Yet this rail line, which took advantage of the shelter afforded by the naturally occurring ravine, was in use only for a few decades. (With the railroad gone, planners found the ravine to be a perfect location for a sewer.) Soon, the tracks were rerouted to assume their approximate present course, which runs parallel to Riverside Avenue on an east-west line from the Winooski River; they bend near present-day Burlington College to a lakeside boatyard about a mile to the south.

One of the streets that the ravine skirted was Orchard Terrace, a stubby little north-south downtown street whose name puzzled Martínez Cazón: no terrace, no orchard. His discovery of the ravine's existence finally explained the "terrace" part: The street once sat on a rise, looking down into a gully some 30 feet deep. But where was the orchard?

Martínez Cazón admires Frederick Law Olmsted not just for the renowned landscape architect's forward-thinking views on urban planning but for his ardent abolitionist and conservationalist stances. Olmsted also meets with Martínez Cazón's favor for offering a clue about Burlington history.

Olmsted wrote in an 1859 book, "I have eaten a better apple from an orchard at Burlington, Vermont, than was ever grown even in the south of England." Though no orchards remain in Burlington, they were commonplace in the city in the 19th century, and one of them inspired the naming of Orchard Terrace.

What began as research into a ravine soon turned into the Olmsted Apple Project, on which Martínez Cazón has collaborated with Citizen Cider. As Seven Days food writer Hannah Palmer Egan recently reported in this paper, the cidery asked Burlingtonians to gather local apples; the fruits were then pressed into a cider that, according to the company's website, "celebrates the history of apples and orchards in Burlington." When the cider is ready to drink, those who do so will almost literally be imbibing the history of their town.

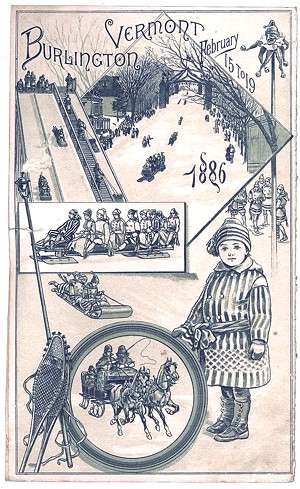

To research the ravine, Martínez Cazón turned to 19th-century local newspapers. Articles about the 1886 Burlington Winter Carnival referred to "traverse races" in the downtown area, and again the historian found himself intrigued. Further research turned up the fact that "traverse" was used to refer to a sort of proto-bobsled — in this case, a steel-runnered craft that seated 12. Ads for the Winter Carnival boasted a traverse course that extended down Main Street's hill, all the way to Lake Champlain.

When he relates this story, Martínez Cazón sounds especially passionate — and why not? All signs point to his having discovered two surprising facts: that bobsledding (for that is what it was) made an unexpectedly early incursion into a small Vermont city; and that it's possible those traverses were, in 1886, the fastest vehicles in the world. He estimates that, on the mile-long course from South Williams Street to the lake (which included a bridge across the ravine), the sleds achieved velocities of up to 60 miles an hour.

Even more surprising was yet another historical find tangentially related to Martínez Cazón's ravine research. In learning about the history of the Burlington waterfront, he found that that same Winter Carnival also hosted the very first international ice hockey tournament. Seems that a smallpox outbreak in Montréal caused organizers to relocate their annual championship southward, to a country where the sport hadn't yet caught on. Carnival poohbahs agreed to host the games on frozen Lake Champlain, and a hastily assembled team of local boys took on — and was summarily humiliated by — the superior Canadian clubs. That same tournament would evolve into the Stanley Cup, which, in 1886 in Burlington, hosted for the first time teams from different countries.

Martínez Cazón is a map geek, not a topographer or geologist, so he can't account for the forces that created the ravine. But he's confident that, even though it's long been filled in, the ravine still exists under many downtown streets. And he figures he's not the only one who'd like to find out more about it. He's not advocating the unearthing of the downtown grid, but Martínez Cazón is keen to know more about what lies beneath the streets of his city.

Though he's considering the idea of turning his findings into a museum exhibit, Martínez Cazón doesn't think that he has a book-length project on his hands. Still, he'd like his meticulous research to form the seed of a larger historical project, so when he's gotten his data into a presentable form, Martínez Cazón plans to release them via online cartography forums and let fellow map geeks have at them.

Ultimately, he says, Martínez Cazón would like to see his maps used for further historical exploration of Burlington. He speculates that the covered-over ravine may be the resting place of all kinds of historical artifacts, from 19th-century plumbers' wrenches to Abenaki arrowheads.

The ravine's history is also the history of the city of Burlington. Its existence, Martínez Cazón says, "explains why the city grew [between the ravine and the lake] and, for a long time, didn't grow on the other side. This [section] was the whole town." Only when the ravine fell into disuse did the city extend eastward, up the hill. "[The ravine] tells the story of why Burlington is the shape that it is, and why it developed the way that it did," he says.

Even beyond that, a historical project such as Martínez Cazón's highlights the interconnectedness of human endeavor. What started as an investigation of a long-defunct railroad track unexpectedly led him through the local histories of agriculture, geology, economics and recreation. Without further investigation, it's impossible to know what else his findings might unearth — literally or figuratively.

"I think this [project] radically opens up the history of Burlington," Martínez Cazón says. "It makes people aware that 'everyday people' are the people who made Burlington unique. And we are a continuity of that."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Researching the Ravine"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

Apr 25, 2024 -

The Café HOT. in Burlington Adds Late-Night Menu

Apr 23, 2024 -

Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s First Term Starts With Major Staffing and Spending Decisions

Apr 17, 2024 -

Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont

Apr 10, 2024 -

Middlebury’s Haymaker Bun to Open Second Location in Burlington’s Soda Plant

Apr 9, 2024 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.