Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Talking With Pulitzer Prize Winner Nicole Eustace Before Her Reading at the Brattleboro Literary Festival

Published October 5, 2022 at 10:00 a.m.

Nicole Eustace is a historian who is "always interested in human beings in their messy multi-dimensionality," she told Seven Days by email. "I think the greatest respect I can pay to my historical subjects is to engage with them as full people, and that means neither vilifying nor canonizing them but rather recognizing their humanity in all its complexity."

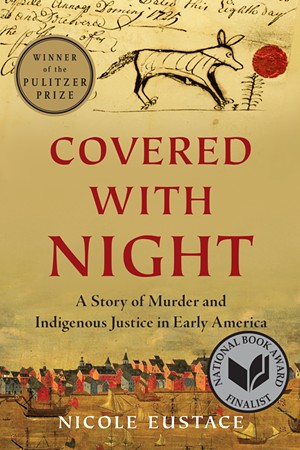

Eustace's third and most recent book, Covered With Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America, is a winner of the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in history and was a finalist for the 2021 National Book Award. She will read at the Brattleboro Literary Festival on Saturday, October 15.

At New York University, where she is a professor of history, Eustace specializes in 18th-century North America, gender, culture, politics and the history of emotion — a growing field that combines historical analysis with psychology and the study of individual and mass behavior, power relations, and community formation.

She also researches and teaches the history of laws, which she called "a culture's best attempts to codify the norms of conduct through which the members of society are to be governed." In Eustace's view, laws reveal "ideas, attitudes and values and are a great starting place to understand the spirit of a people."

Covered With Night brings to the fore an obscure incident from 1722 and its repercussions, which Eustace believes are still felt today.

A native Seneca hunter named Sawantaeny was killed in a drunken argument with two brothers, the white traders John and Edmund Cartlidge. Colonial officials in Pennsylvania feared that the murder might set off a war with the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) federation, whose power at that time rivaled or exceeded the influence and military might of the English to their south and the French to their north. Therefore, the Cartlidge brothers were imprisoned, with the expectation that they'd be executed to appease their victim's people.

But the Indigenous people in the region took a completely different approach to justice in the case, as Eustace learned by poring over detailed contemporary accounts, including newspaper articles, minutes of government hearings, letters, diaries and records of treaty negotiations.

She tells the story of three intermediaries, speaking three different languages, who effectively coordinated a diplomatic breakthrough: the Iroquoian speaker Satcheechoe; the Susquehannock speaker Taquatarensaly, also known as Captain Civility; and Alice Kirk, an Anglo woman who could translate the Native language Delaware into English. Their method was an early example of what today we'd call "restorative justice," a technique that replaces punishment with an apology, reparations and reconciliation.

The hundreds of citations in the back of Covered With Night confirm the breadth and depth of Eustace's investigative skills, but immersive scholarship alone can't account for the vigor and vividness of her storytelling. Eustace is a marvelous chronicler, and her book has the narrative power of a novel.

In an email exchange with Seven Days, Eustace shared how she discovered the 1722 incident and offered observations on the differences between European and Indigenous views of justice and the lasting significance of 18th-century treaties.

SEVEN DAYS: Covered With Night pivots on an incident from 300 years ago that few remembered. When in your research did you realize how important the year 1722 was?

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- Covered With Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America by Nicole Eustace, Liveright, 464 pages. $20.

NICOLE EUSTACE: I set out to investigate how Enlightenment ideas about civilization and savagery impacted cross-cultural relationships between Anglo-American settler colonists in Pennsylvania and the Indigenous peoples of the Susquehanna River Valley. I began reading the Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, knowing they contained extensive records of what were then called "Indian treaties," and that these could convey a great deal of information about Native perspectives on the encounter with Europeans. I discovered that the year 1718 marked a major turning point in Pennsylvania's criminal law codes, which were made much more severe after colony founder William Penn's death that year. I then stumbled on a 1722 murder case that tested those laws. Colonial fur traders brutally attacked a Seneca hunter, but Native people sought reconciliation rather than revenge. The detailed notes of their arguments drew me in, and I knew I'd lucked into a story that deserved to be told.

SD: Where did you first encounter the Susquehannock interpreter and diplomat Taquatarensaly, known as Captain Civility?

NE: The Native man known as Captain Civility took a central role in trying to explain Indigenous principles of justice to incredulous and uncomprehending settler colonists. He tutored colonists on Indigenous methods of conflict resolution, showing them that even a murder crisis could provide an occasion to strengthen ties of community.

Because I was interested from the start in thinking critically about settler colonists' claims to so-called civilization, coming across an Indigenous man called Captain Civility seemed extraordinarily significant. I found in my research that this was an Indigenous job title used by generations of Susquehannock diplomats tasked with bridging divides between different Native nations, tying disparate peoples together in civil society. Taquatarensaly's name incorporates the Susquehannock word "attaqua," meaning "shoes," which conveyed his role of walking between peoples, joining them in community.

SD: Which writers — historians and literary artists — have been your models for creating prose that's so engaging, both informative and exciting?

NE: I've long admired the historical method known as microhistory — small stories with big implications — first introduced by the historian Natalie Zemon Davis. Building on the research of my fellow scholars, especially Indigenous historians such as Alyssa Mt. Pleasant, Jean O'Brien, Michael Witgen and others whose work informed and enriched my analysis, I wanted to experiment with using techniques of creative nonfiction. The phenomenal writing of Hilary Mantel, an incomparable novelist with an intense commitment to history, helped me see the drama in history in a new way.

SD: You call the Great Treaty of 1722, which resolved the murder crisis, "the oldest continuously recognized Indigenous treaty in Anglo-American law." What is the lasting significance of those treaties negotiated and ratified between colonial and then federal governments and tribal nations?

NE: Treaties set out tribal rights of Native nations that remain key elements of their legal claims to national sovereignty and land tenure to this day. They are an essential aspect of Indigenous rights. They are also a repository of Native culture, intellectual history and political philosophy, containing intricate speeches delivered by Native speakers on the basis of community consensus. In Covered With Night I draw on treaty council records as a primary source for 18th-century Indigenous history and for Indigenous theories of justice specifically.

SD: In the story you tell, Native negotiators demonstrate tremendous ambassadorial skill, subtle philosophical reasoning and sophisticated political understanding. Yet you never idealize the Haudenosaunee people nor villainize their Anglo-American counterparts.

NE: As a historian, I am not interested in straw men or cardboard cutouts of characters. No matter who or what I'm writing about, I'm always interested in human beings in all their messy multi-dimensionality. Particularly in portrayals of Native people, polarizing stereotypes of cruelty versus nobility have been pernicious for centuries, to the point that Indigenous lives and experiences have been flattened almost beyond recognition. So, I think there's an extra ethical responsibility to try to portray Native people in three dimensions.

SD: The example of a historical "truth and reconciliation" process described by Covered With Night must be very relevant to those now questioning our reliance on incarceration and punishment, including the death penalty. Have you heard from readers who find this story especially meaningful in showing an alternative to punitive justice?

NE: Yes, I have heard from Native activists and advocates of criminal justice reform, as well as people working on racial reconciliation projects at every level, from local to national. This response has been absolutely the most rewarding aspect of writing the book. History can sometimes seem abstract; to know that my work is helping to inspire and support those taking active roles in progressive causes has made me feel that all the hours spent alone at the keyboard can have an impact out in the world.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Justice Revisited"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About The Author

Jim Schley

Bio:

Contributing writer Jim Schley has edited nearly 200 books in a wide range of genres and subject areas. He leads book discussions around the state for Vermont Humanities. And as a theater artist, having toured internationally with Bread & Puppet and the Swiss troupe Les Montreurs d’Images, currently he’s performing with Parish Players and BarnArts. He lives in Strafford.

Contributing writer Jim Schley has edited nearly 200 books in a wide range of genres and subject areas. He leads book discussions around the state for Vermont Humanities. And as a theater artist, having toured internationally with Bread & Puppet and the Swiss troupe Les Montreurs d’Images, currently he’s performing with Parish Players and BarnArts. He lives in Strafford.

Speaking of...

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Lydia Kern Receives Fourth Annual Diane Gabriel Visual Artist Award Arts News

- 2. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, May 15-21 Magnificent 7

- 3. How Do I Get Through My First Mother's Day Without Mom? Ask the Rev.

- 4. Q&A: At the Lanpher Memorial Library in Hyde Park, a "Wind Phone" Connects Callers With Lost Loved Ones Stuck in Vermont

- 5. 'Heavy Kinship' at the Tarrant Gallery Contemplates Bodies and Connectedness Art Review

- 6. Video: Visiting the Wind Phone at the Lanpher Memorial Library in Hyde Park Stuck in Vermont

- 7. Theater Review: 'tick, tick… BOOM!,' Vermont Stage Theater

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 3. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 4. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 5. Video: Visiting the Kellogg-Hubbard Library’s PoemCity in Montpelier During the Month of April Stuck in Vermont

- 6. Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate Poetry

- 7. Monsignor John McDermott Named Bishop of Burlington Books