Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

What Route 100 Says About Vermont: A Journey in Five Parts

Published August 24, 2022 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 19, 2022 at 5:00 p.m.

On a summer night in 1978, I hitchhiked in both directions on Route 100. I was 19 and had the next day off from my summer camp job in Hancock. When I saw approaching headlights, I stood on that side of the road and stuck out my thumb. Each way held promise.

A ride north would lead to the Mad River Valley and a day of swimming-hole hangouts and hikes. A hitch just a few miles south would take me to Rochester for a beer at the now-bygone Rochester Inn.

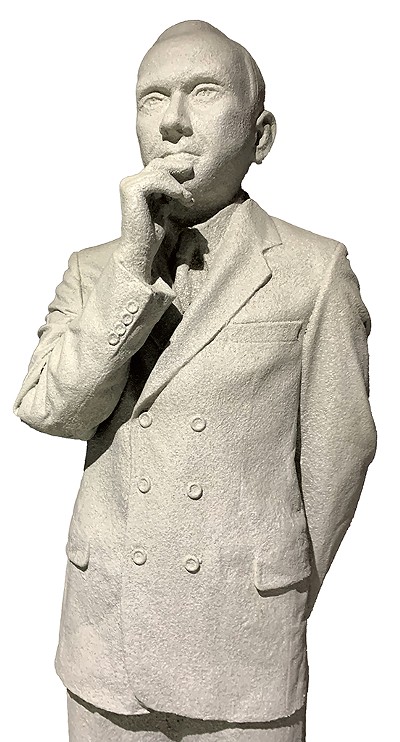

Many summers later, Route 100 still offers adventure, exploration and beer. The 217-mile road is the only state highway that traverses the length of Vermont, running from Stamford at the Massachusetts border to Newport, a few miles south of Canada.

The highway passes through ski towns and runs by farmland and national forest. It connects with dirt roads and an interstate highway; parts of it are called Main Street. It has been wrecked more than once by storms and floods — and rebuilt.

In the days after Tropical Storm Irene in the summer of 2011, then-governor Peter Shumlin and then-lieutenant governor Phil Scott traveled the state, visiting places affected by the storm. Route 100 demonstrated "front and center" the character of Vermont, now-Gov. Scott said in a recent phone call.

"It really showcased the hardiness of different communities along the way," he recalled.

To explore the character of the state and get a sense of its history, five Seven Days reporters recently drove the length of Route 100, each reporting on a roughly 40-mile stretch.

Enticed by the state vegetable, Jordan Barry journeyed to the southernmost section, where she found emerging entrepreneurs and makers. In Plymouth, where Calvin Coolidge was born and took the oath of office half a century later, Dan Bolles found the 30th president's famously quiet manner rubbing off on him. In the middle of the state, Melissa Pasanen traveled a corridor of artists and craftspeople on the same stretch of 100 that I hitchhiked years ago.

I delved into the history of the stretch between Waitsfield and Morrisville and emerged in awe of the people who built the Waterbury Dam for flood control. On the road's northernmost section, Paula Routly saw evidence of old and new ways to use natural resources. She also visited a convent whose residents seem to draw their resources from a more spiritual realm.

Route 100 has existed in some form for at least a century. On a 1923 state map, a route marked "100" runs from Ludlow to Newport. The designation was a "wayfinder," not a state highway, said Johnathan Croft, a cartographer and chief of the mapping division for the Vermont Agency of Transportation.

In 1931, when the legislature created the state highway system, two sections of Route 100 were included in the original 1,000 miles: Waterbury to Newport (51 miles) and Killington (then called Sherburne) to Stockbridge (11 miles). The system was established to provide state aid for roads that would help relieve the burden on towns after the 1927 flood, Croft said. He called the flood a "watershed moment" for state highways.

"Since 100 is essentially hugging the spine of the Green Mountains, it really is a very scenic and kind of a sinuous road," Croft noted.

Seven Days' summer road trip offers a view of Vermont's past, present and even future that Gov. Scott might recognize from his own trips on Route 100.

I called him, thinking Vermont's race car-driving governor might reveal a section of 100 where he likes to let it rip. But it turns out Scott prefers to travel the road by bicycle. On a succession of rides, he said, he has pedaled the whole route. He appreciates the opportunities that the pace of biking gives him to see the scenery, stop at general stores and talk with people.

"It really is quintessential Vermont when you take that road," Scott said. "It may not be the fastest from one end of the state to the other, but it's the most beautiful. And it does tell a lot about the communities that we all love."

— S.P.

Turnips, Glory Holes and New Investments

Stamford to Jamaica

I set out for southern Vermont in search of a turnip. Or a rutabaga-turnip cross, really. Whatever the gnarly white-fleshed, light green-skinned vegetable is, I knew I'd find it in the winding mountain roads of Wardsboro.

The Gilfeather turnip became Vermont's official state vegetable in 2016. John Gilfeather developed the hybrid under mysterious circumstances in the early 1900s, right off Route 100 on what is now Gilfeather Road.

Throughout my trek up Route 100 with my husband, from the Massachusetts border to Jamaica, I kept my eyes peeled for the special turnips, which I hope to plant in my garden this fall. Along the way, I encountered some bizarrely named infrastructure, new-to-town entrepreneurs making a mark on the food scene, and a "community of craft" that makes the most of seasonal ski-town living.

In Stamford, where Route 100 runs concurrently with Route 8, wind turbines seemed to bounce from the left side of the road to the right. When the numbered roads diverged eight miles in, Route 100 immediately felt like Route 100, or at least like the tree-lined, river-following northern parts with which I'm familiar.

We started by satisfying a bit of curiosity: I had to see Harriman Reservoir's Glory Hole.

The eight-mile-long reservoir — also called Lake Whitingham — is the largest body of water entirely within Vermont. The unfortunately monikered Glory Hole spillway is near the southern end, on Dam Road. You can't get very close to the expansive concrete funnel, approximately 160 feet wide, but from above we marveled at the huge ring as water trickled in.

We took Brian Holt's recommendation for a swimming spot on the other side of the lake. The co-owner of Wilmington's 1a Coffee Roasters directed us to the Mount Mills West Picnic Area, a few minutes past his café on Route 9.

"A lot of people underestimate how amazing the lake here is," Holt said. "Once you know about it, it's one of those dreamy places."

Holt and his wife, Chrystal, opened their solar-powered roastery and coffee shop half a mile from the intersection of Routes 100 and 9 in September 2020. The couple were living in Helsinki, Finland, when a friend alerted them to the town's Wilmington Works Make It on Main Street business competition.

"I don't think I'd ever stepped foot in Wilmington when we submitted for it," Holt said. Their pitch won, tying with two others, but the building they purchased is just past Wilmington's designated downtown district, so they weren't eligible for the split prize.

"We're happier here than having $10,000 and being stuck in the traffic zone," Holt explained. Wilmington's main intersection — with its array of restaurants, shops and inns — gets busy on big holidays and summer weekends. It has the only stoplight I encountered from Stamford to Jamaica, besides two flashing yellows by Mount Snow in West Dover.

The Holts quickly settled in and expanded their investments in the area, opening a second location at the base of Mount Snow last winter. They bought the building that now houses Starfire Bakery and, in early August, closed on Wilmington's Old Red Mill Inn; they're part of a team that will bring a brewery to the space. Head brewer Justin Maturo's first Valley Craft Ales releases are already on the market, and the team hopes to pour at the inn's bar by the end of September.

As we pulled into Wardsboro, home of the Gilfeather turnip, I thought about how its namesake hauled wagonloads of it down the mountain to markets in Brattleboro and Massachusetts — after he chopped off the tops and roots to prevent others from collecting seeds.

These days, the vegetable is easier to find — and to grow. "Welcome to Wardsboro" signs on Route 100 proudly proclaim the town "Home of the Gilfeather Turnip."

In late July, I was a few months early for the real thing. The sweet Gilfeather is a fall crop, made even sweeter by a hard frost or two. Wardsboro's annual Gilfeather Turnip Festival happens in late October, when thousands of turnip lovers and pounds of turnips hit the town, population 869.

But I wasn't after turnip soup, latkes, cupcakes or mash. I wanted seeds, so I headed to the Wardsboro Public Library.

The library occupies a renovated 1840s farmhouse and attached barn just off Route 100. Inside, tucked between bookshelves, I found a display case dedicated to the Gilfeather.

While plenty of libraries offer collections of seeds for community members to grow, Wardsboro might be the only place where seeds help the library grow. Proceeds from each $4 packet of tiny Gilfeather turnip seeds — grown by Dutton Berry Farm in Newfane and packaged by the nonprofit Friends of the Wardsboro Library — have long funded the library's preservation and maintenance. In November, voters will decide whether the town should take over its operation.

"Last year, we sold over 100 packets through mail order," Linda Gifkins told me. She's on the Friends of the Wardsboro Library board and chaired the past five Gilfeather Turnip Festivals. "They go all over: North Carolina, Oregon, Montana. How they find us, I don't know."

It's harder to track where the seeds go when they're picked up at the library. I paid by tucking cash into a wooden box, along with $20 for the third edition of The Gilfeather Turnip Cookbook.

Farther north, at West River Provisions in Jamaica, I bought a four-pack of Valley Craft Ales' High Performance Pontoon, an American porter made with 1a's cold-brew coffee. Like the Holts, Tara and Forrest Riley are relatively new to the area; they moved to Jamaica from Connecticut, specifically to buy the general store, in January 2021. Tara grew up camping at Jamaica State Park, which sits just over a bridge behind the store.

"It's hard to make a life up here," Tara said. "But sometimes a place just gives you a feeling that makes you know it's home, and Jamaica always had that for me."

Big ski mountains — Mount Snow, Magic Mountain, Bromley and Stratton — draw lots of folks to the area in the winter. But life is seasonal for many of the locals. "Nobody has one gig," Tara said.

That versatility has created what she called an "almost overwhelming community of craft" — including woodworkers, soap makers, screen printers, potters, farmers and brewers, all of whom she works with to stock the store. "You don't have to leave your little 20-mile radius, because it has everything you need," Tara said.

We explored the packed aisles, then grabbed doughnuts made in-house by Tini Henrich of the Skinny Goose bakery. We ate them across the bridge in the state park and washed our hands in the West River after licking off every bit of maple glaze.

Signs advertising a farmstand, garden yoga, a Sunday breakfast and a Saturday barbecue with live music pulled us to the left on our way out. One driveway down from the park entrance, Christina and Jamar Robinson have created a vibrant community space at their Bee Well Homestead. Jamar was busy setting up for that night's event, but we chatted briefly in the lush garden, and I got a quick lesson on how to top my Brussels sprouts for an early crop.

Unable to stay for the festivities, we stocked up on cucumbers and locally brewed kombucha for the trip home.

Jamar told us to return to this stretch of Route 100 soon, adding, "There's a lot of epicness on this road."

Pit Stops

- 1a Coffee Roasters, 1acoffee.com

- Friends of the Wardsboro Library, friendsofwardsborolibrary.org

- West River Provisions, facebook.com/westriverprovisions

- Valley Craft, instagram.com/valleycraftales

- Bee Well Homestead, beewellhomestead.com

— J.B

Cal Is My Copilot

South Londonderry to Plymouth

President Calvin Coolidge's 1928 "brave little state" speech is perhaps his most famous, at least in Vermont. Delivered in Bennington as Coolidge surveyed recovery efforts after the 1927 flood, the paean to the Green Mountain State experienced a revival in 2011, after Tropical Storm Irene.

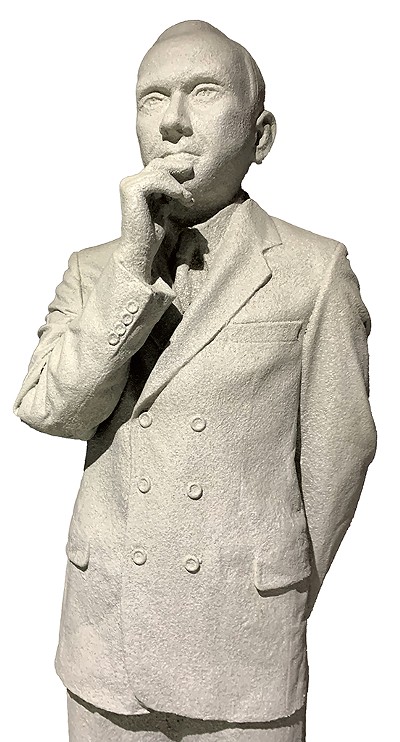

However, Vermont exceptionalism wasn't at the top of my mind when I recently toured the museum and grounds of the President Calvin Coolidge State Historic Site along Route 100A in Plymouth Notch. Instead, I found myself thinking of a lesser-known Coolidge quote: "I have never been hurt by what I have not said."

America's 30th president was shy and stoic — hence his nickname, "Silent Cal." (When Coolidge died in 1933, poet Dorothy Parker quipped, "How could they tell?") While I might not have agreed with all of his policies, I do have a soft spot for a quiet man who succeeds in the loud arena of politics.

The taciturn Coolidge — he was said to be "silent in five languages" — was sometimes considered cold or aloof. As I lagged behind a guided tour of the rustic Vermont village where he lived, nestled in a hollow among rolling, wooded hills, I wondered whether his detachment was the product of something else. Maybe the man simply enjoyed peace and quiet.

click to enlarge

- Dan Bolles ©️ Seven Days

- Calvin Coolidge statue at President Calvin Coolidge State Historic Site

As I considered that possibility, it seemed fitting to explore the section of Route 100 between Plymouth and South Londonderry as ol' Silent Cal might have — quietly.

With Cal's silent spirit riding shotgun in my Mazda3, I headed south from Plymouth Notch, gliding along 100 with the windows down and sunroof open. My destination was the intersection of Routes 100 and 30, just south of South Londonderry, from which I would wind my way back north once I had the lay of the land. But, as the old road-trip adage goes, half the fun is getting there.

This 44-mile stretch of 100 starts by cutting through the heart of the 21,500-acre Coolidge State Forest. North of Ludlow, the road hugs placid lakes and ponds dotted with summer camps, from well-to-do Farm & Wilderness camps on the Woodward Reservoir to lake houses and resorts along Amherst and Echo lakes.

It's tempting to hit the gas through this gently curving stretch of blacktop, but traffic flows at a leisurely pace, as if the relaxed vibes from summer homes wafted on the breeze.

Past Ludlow, 100 jags west through the Okemo State Forest, then south to Weston and Londonderry, eventually joining Route 30 in Jamaica. Technically, 30 was a bit south of my assigned end point. But friends from southern Vermont had insisted I stop at Honeypie, a next-level fast-food joint in a converted gas station at the intersection of 30 and 100. And, as Coolidge himself once said, "If we did not have the privilege of doing what we wanted to do, we had the much greater benefit of doing what we ought to do."

It's not that I wanted to stop for the O.G. (a perfectly charred two-patty smash burger with tangy special sauce), shoestring fries and a vanilla shake; I was obliged to. Plus, while talking up fellow diners on Honeypie's lawn, I scored a tip for my next stop.

I had planned to find a hike with a view. My chatty neighbors, an outdoorsy young couple from Northampton, Mass., rattled off a few spots I recognized from perusing AllTrails. But, one of them suggested, "If you're more about the view than the hike, you could ride the gondola at Stratton and walk to the fire tower." About 20 minutes later, I stood at the base lodge of Stratton Mountain Resort, just a jog away from 100 off 30. A ski resort in August can seem as desolate as a beach town in March. Stratton was a little more animated, with a smattering of mountain bikers, golfers and wedding goers, but there was no lift line for the gondola.

After a slow, scenic ride to the top of the mountain (elevation 3,875 feet), I followed trail signs and a few other tourists to the fire tower in the woods. A sign on the old, four-story structure advises that only four people climb the tower at one time. So I waited my turn before ascending the steps behind a pair of Japanese exchange students from Georgia Tech.

The narrow, rickety wooden staircase didn't assuage my mild fear of heights. But the cramped observation deck probably offers the best view-to-hike ratio in the state. The 360-degree panorama features peaks and valleys in four states: Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and New York.

The vista brought to mind a line from Cal's most famous speech: "I could not look upon the peaks of Ascutney, Killington, Mansfield and Equinox without being moved in a way that no other scene could move me."

Or, as my new Japanese friends put it, "Wow."

Back on solid ground, I traveled north on 100 through Londonderry on my way to Weston, home of the Weston Theater Company, a cornerstone of summer theater in Vermont. Given my low tolerance for musicals, I passed on the closing performance of Hair — though I enjoyed hearing the exultant finale spilling from the theater as I walked the stately town green.

My feelings about musicals aside, I do have an affinity for kitsch. Between the Weston Village Store, Vermont Country Store and Weston Village Christmas Shop, all bunched together along 100, tiny Weston might boast the densest population of tourist traps in the state — and I mean that lovingly. In which other 30-yard radius can you score a sparkly nutcracker ornament, a Vermont-shaped cutting board and Barack Obama socks?

Perhaps Cal's spirit was ushering me on, because after perusing the mini shopping district's gaudy wares, I craved a more contemplative scene.

Weston Priory is a Benedictine monastery just off 100 on Route 155, about six miles north of Weston Village. Founded in 1953 and open to the public, the priory offers daily common prayer, retreats and sometimes singing monks. But I was drawn to the St. John XXIII Labyrinth, a stone circle inlaid in the grass on the edge of the priory's serene campus. The idea is pretty simple: Shut up and walk around the maze.

A small sign at the entrance offers more specific instructions for "A Meditation Walk & Journey of the Heart": "Walk slowly. Follow the Path. Look... Listen... Be Still."

The solitude was indeed refreshing, but it left me wanting to be around people again. So I continued north to Ludlow, the ski town in the shadow of Okemo Mountain Resort.

My first stop was the upscale Main + Mountain Bar & Motel. On the advice of a friendly bartender from Chile, I settled on a specialty drink called a Pretty Bird. I sipped the pineapple-y, bourbon-based cocktail on the outdoor patio overlooking a bustling Main Street, which is really more my style of meditation, anyway.

The day was getting long, and I planned to camp overnight at Coolidge State Park. So I made my way down Main Street to Gamebird, a retro arcade and fried chicken joint, where I ordered takeout. While I waited, I played Skee-Ball and set a high score on Centipede. Must've been all that meditating.

From Ludlow, I raced the setting sun north to the campground. I barely found my site and pitched my tent before dark. After dinner, I sat alone by the campfire and enjoyed Cal's namesake park the way I imagine he would have: in silence.

Pit Stops

- Calvin Coolidge State Historical Site, historicsites.vermont.gov/calvin-coolidge

- Honeypie, eatathoneypie.com

- Stratton Mountain Resort, stratton.com

- The Benedictine Monks of Weston Priory, westonpriory.org

- Main + Mountain Bar & Motel, mainandmountain.com

— D.B.

A Golden Ribbon of Craft

Killington to Warren

I was driving north toward Killington Resort when a fairy tale-worthy stone tower popped unexpectedly into view. A hairpin right led me to a white stone church with a red door and discreet rooftop crosses.

Words carved on a huge rock told me that Josiah Wood built his home on the site in 1783, and a plaque nearby indicated that it's on the National Register of Historic Places. I was at the Church of Our Saviour, where another sign listed a schedule of services held in the orchard.

Vicar Lisa Ransom's office hours on the guesthouse porch had not yet started, but she gladly showed me around. Ransom explained that the church was commissioned in 1895 by Josiah Wood's daughter, Elizabeth Wood Clement, who deeded the 180-acre property to the Episcopal Diocese of Vermont.

There are public trails, a small garden, beehives and laying hens. "The church is always open, and the chickens are usually out," Ransom said.

Built from Plymouth granite with a vaulted, wood-paneled sanctuary and jewel-toned stained-glass windows, the beautiful little church set the tone for my journey, which was rich in historic and contemporary craftsmanship.

When I pulled into Stone Revival Gallery & Gift Shop in Stockbridge, John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads" was playing from M. Julian Isaacson's speaker as he chiseled white marble. Local stone drew the sculptor back home to Vermont in 2008, after decades on the West Coast.

Isaacson grew up about 13 miles north in Hancock, where his New York City artist parents moved in 1949 and raised seven kids. He returned to be closer to family. "It's where the marble is," he added.

A tractor trailer of logs rolled by on Route 100. The road still features a couple of lumberyards, but for the most part, Isaacson said, "Vermont has turned from wood and stone to tourism."

He picked the Stockbridge spot to help market his work. "People around here call 100 'the golden ribbon,'" he said. "It's all about exposure."

Located midway along my Route 100 stretch, Rochester boasts an expansive park with the classic bandstand and war memorial. From there, I headed a few minutes into the hills to Jeremy Seeger's modest home and dulcimer workshop.

A nephew of musician-activist Pete Seeger, Jeremy first came to Vermont in 1964 to visit Killooleet, a summer camp on Route 100 in Hancock, then run by another Seeger uncle and his wife and now owned by the next generation. He found his calling in the camp craft shop, which he oversaw for the next 15 summers.

"My gift is working with my hands," Jeremy said, before playing a quick tune on a mountain dulcimer he'd crafted from cherry and mahogany.

From the start, Jeremy felt at home in the valley. "There was a lot of small industry here. There were craftspeople living here," he said. "People like me came to Vermont and found it a good place to live and create."

Jeremy makes a living, but that's not easy in rural Vermont, he said. His dulcimers start at just under $1,000. Customers occasionally drop by, he said, but "everything is far from here."

Remoteness does foster homegrown creative community. Jeremy is devoted to the White River Valley Players, a Rochester theater group, as is artist Judy Jensen. She has a home gallery in a part of Rochester named Talcville, after the long-defunct talc mine.

Jensen started visiting Rochester from Philadelphia as a child. She and her husband moved up in 1972 and raised two kids, as well as 120 sheep. "We were hippies," she recalled as she harvested tomatoes in her prolific garden.

Her barn gallery is open "whenever," Jensen said, and filled mostly with pottery, from whimsical teapots embellished with shells or octopus tentacles to voluptuous, midriff-shaped "sexpot" vases. She recently published an endearing picture book with scratchboard illustrations, and she hosts a weekly live model painting group.

"If you have a couple people doing something in the arts, other people want to be around them," Jensen said of the local creative energy.

Jensen lives across Route 100 from Liberty Hill Farm, a scenic dairy owned by the Kennett family. I spent the night there, joining other farm-stay guests for dinner and breakfast.

While Beth Kennett prepared sausages and rhubarb clafouti, her husband, Bob, paused to chat. When they bought Liberty Hill in 1979, "there were 11 farms shipping milk in the valley. Now, we're the only one," he said.

"All the industries are gone," Bob continued, listing the Rochester bobbin and talc mills, the Hancock plywood mill, and the Granville clapboard and bowl mill.

I set off through the morning mist to visit a rare exception. North of town, up Quarry Hill Road, the Fabbioli family and their small crew still excavate Vermont Verde Antique serpentine stone destined for courthouses, banks and countertops. I climbed onto a rough hunk of dark green stone to peer over the fence and deep into the historic quarry.

Continuing north to Hancock, I turned up a hill past several strongly worded "no trespassing" signs to the home studio of master bird carver Floyd Scholz.

The feathers of a red-tailed hawk looked so real that I initially doubted they were crafted from wood and paint. Scholz works on commission for collectors around the world who pay up to tens of thousands of dollars for each piece. He offers carving seminars in Bennington, has published several popular carving reference books, and is an accomplished banjo and guitar player.

In 1980, the Connecticut native was a National Collegiate Athletic Association decathlon champion headed to the Olympics — until the U.S. boycott. "Feeling sorry for myself," he recalled, he packed his instruments and tools and drove to Granville, north of Hancock, to help build a log cabin.

The young man worked in logging and construction until his hobby generated $7,000 for a prizewinning carved crow, more than he'd earned in the past six months.

Scholz travels a lot, but the peace and woods of Vermont are his anchor. "I'm going to be buried in Hancock," he said.

In nearby Granville, a decrepit industrial complex appeared abandoned, but in an office I found Jeff Fuller, Granville Manufacturing's sole remaining owner-employee.

Fuller's family moved from New Jersey and bought the clapboard and wooden bowl mill in 1981. At its peak, it employed 40, including six family members. "Peggy Potter used to paint our bowls," Fuller said, referencing the mother of musician Grace Potter, a Waitsfield native.

Granville Manufacturing ceased manufacturing in 2008. "We were very good at losing money," Fuller said ruefully. He has since worked alone, selling clapboard made in Moretown and the occasional bowl from the company store's dusty shelves. "I see ghosts," he said.

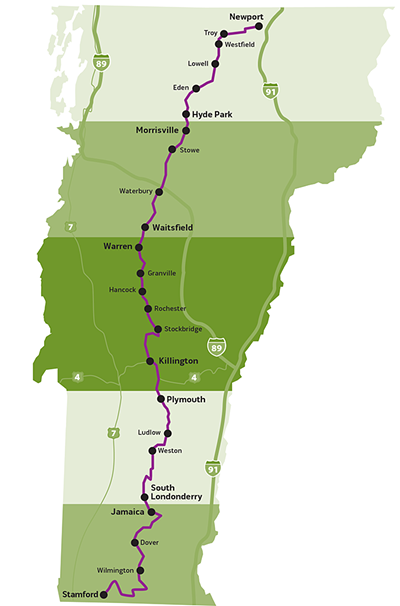

Next door, glassblower Michael Egan was taking a break from hot work on a hot day. Egan said he relishes the physical and artistic challenges of molten glass: "At the end of the day, I'm exhausted but elated."

Egan apprenticed in Burlington but chose to live and work near Waitsfield, where he grew up. He opened Green Mountain Glassworks in 2000. "I thought it'd be good to be between ski areas, but Irene really changed things," he said, noting that tourist traffic never fully rebounded after the storm.

His kaleidoscopic vases and ornaments sell well through craft galleries and museum stores, but studio sales are slow. Egan sometimes wishes he could move north on Route 100, to Stowe.

"This is not a location for business," he said. "It's a location for creativity, inspiration and retirement."

Pit Stops

- Church of Our Saviour and Mission Farm, missionfarmvt.org

- Stone Revival, stonerevival.com

- Jeremy Seeger Dulcimers, jeremyseeger.com

- J. Jensen & Friends Fine Craft Gallery, 2059 Route 100, Rochester

- Liberty Hill Farm, libertyhillfarm.com

- Vermont Verde Antique, vtverde.com

- Floyd Scholz, floydscholz.com

- Green Mountain Glassworks, michaeleganglass.com

See a profile of Art in the Village Gallery and read about Hostel Tevere; both are just off Route 100 in Warren.

— M.P.

Undercover as a Tourist

Waitsfield to Morrisville

I threw the essentials in the back of the car — a cooler and my bathing suit — and hit the road for a day of playing tourist in my home state. My itinerary was guided by two self-imposed rules: Being inside for more than five minutes at a time was forbidden, and so was stopping at big-name tourist destinations. So eating a Cherry Garcia ice cream cone at the Ben & Jerry's factory in Waterbury was out, as was sidestepping 100 to ride the gondola up Mount Mansfield at Stowe Mountain Resort.

Instead, along this well-traveled section of Route 100, I sought out lesser-known places where I could look back in time to learn about Vermont's human and natural history.

click to enlarge

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Molly Ciminello serving an ice cream sandwich at the Sweet Spot in Waitsfield

To the soundtrack of Don Henley's "The Boys of Summer," I drove to my starting point: Mehuron's Supermarket in Waitsfield. The family-owned grocery has been supplying food to people in the Mad River Valley for 80 years. At the deli counter, I got a hummus, feta and olive sandwich and rounded out the purchase with water, chips and ice for the cooler.

With lunch packed away for later, I stopped for a snack at the Sweet Spot, a window-service café by the 1833 covered Great Eddy Bridge in Waitsfield's historic village. Tucked in a courtyard above the Mad River, the Sweet Spot is shaded by a pergola and bordered by flowers. I ate a fabulous coffee ice cream sandwich and watched kids swim in the river. I wanted to join them, but the road beckoned.

Route 100 passes a few farms in the flats along the river, including a dairy with a cow crossing under the highway, before the road divides and 100B leads to Middlesex. I followed the main route past Harwood Union Middle & High School into Waterbury.

Guided by my interest in the history of the highway, I drove through the Waterbury Roundabout and detoured off Route 100 for about a mile, traveling west on Route 2 to get to Little River State Park. The park is the site of the Waterbury Dam, which was built in the wake of the flood of 1927, a catastrophic event in which 84 people died and bridges and other infrastructure were wrecked. The dam was constructed to help prevent future natural disasters of that magnitude and to provide protection and resources to the region — including Route 100.

To walk across the 500-meter expanse on top of the earth-filled dam and look down at the 860-acre reservoir is to marvel at the engineering and construction of both. The 2,000 men who built the dam in the mid-1930s, laying each stone by hand, lived at Camp Charles M. Smith, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp whose relics remain in the woods at the state park.

click to enlarge

- Sally Pollak

- Birdhouse art installation on the Lamoille Valley Rail Trail in Morrisville

Walking the universally accessible path through the camp, I saw old stone fireplaces and building foundations — vestiges of a once-teeming site of 27 barracks and 13 mess halls. The camp had its own water system and police department, along with stores, a library and a skating rink. Notes from a 1937 camp yearbook, reproduced on a sign in the woods, describe the "ominous night of Wednesday, November 2, 1927 when rain, falling gently at first from a sultry sky," set the flood in motion.

From the camp, I drove a few miles north on 100 to Waterbury Center State Park, also on the reservoir. With a beach, a boat launch and mountain views, the park is a terrific place for swimming, picnicking, kayaking or reading. I was delighted to cool off in the water after one walk and before the next.

My second walk started a few miles down the road on the Short Trail, behind the Green Mountain Club visitor center. The club stewards the 272-mile Long Trail, which, like Route 100, traverses the length of Vermont. A hiking teaser, the Short Trail is a half-mile loop marked by signs that describe Vermont's natural history and explain its landscape.

Walking on the path, I learned about the glacier that covered the region 20,000 years ago, the stone walls that were built two centuries ago to contain grazing merino sheep and the evergreen stands that are today's deer habitat.

This oasis in the woods is a few miles from Stowe, the ski town and tourist mecca filled with shops, restaurants and slope-side condos. Driving the road to Stowe, I saw glimpses of Mount Mansfield, Vermont's highest peak, and mountains in the Worcester Range. At the edge of town, I stopped at Mansfield Dairy, which sells milk, cheese and eggs in the annex of a brick farmhouse.

Proprietor Allene Small has lived in Stowe for all but four of her 88 years. "Think I'll be here when I'm 100?" she asked with a smile. Traffic and tourism have increased substantially during her five decades in the farmhouse.

"Sometimes people have to wait five minutes to [drive] out of here," Small said.

We talked about her childhood on a 20-cow farm in Stowe Hollow. She recalled carving her initials into a truss of Gold Brook Covered Bridge, so I drove to the span to look for her inscription.

I didn't find it, but I walked down the hill to the river and waded in the brook. I imagined Small, 80 years ago, playing under the bridge with her siblings and cousins.

"It was a fun thing to do in the summer," she'd told me.

I found summertime fun in Morrisville, the last town on my route, where I stumbled on a country-rock concert at Oxbow Park. The barefoot singer leading the band was Lesley Grant, music teacher at Hyde Park Elementary School. Grant sang country classics as kids ran in the grass and adults played outdoor ping-pong and chatted with friends. The line for cheeseburgers and fries, cooked by the auxiliary of the Morrisville Fire Department, was buzzing.

The sun was sinking behind me as I took the day's last walk, following the Lamoille Valley Rail Trail east along the Lamoille River. The path led past a colorful installation of birdhouses in a field of high grass and wildflowers.

In the still of the evening, I thought of my conversation with Maud Le Guennou, a tourist from Montréal whom I'd met at the covered bridge in Stowe. A 36-year-old graphic artist, Le Guennou was visiting Vermont with her husband and 3-year-old son.

"It's really peaceful here, and it's really about the outdoors," she said. "That's what we were looking for."

Pit Stops

- Mehuron's Supermarket, mehurons.com

- The Sweet Spot, thesweetspotvermont.com

- Little River State Park, Vermont State Parks, vtstateparks.com

- Green Mountain Club, greenmountainclub.org

- Mansfield Dairy, mansfielddairy.com

- Oxbow Park, morristownvt.org

- Lamoille Valley Rail Trail, vtrans.vermont.gov/lvrt

— S.P.

Off-Off-Road

Hyde Park to Newport

The northernmost stretch of Route 100 doesn't make it easy for tourists. "Open" flags and state-sanctioned business directional signs are few and far between. Fancy coffee drinks are nonexistent.

But if you're willing to make the effort, as my significant other and I did on a recent sweltering Saturday, there are some hidden gems along the portion of the road that connects the towns of Hyde Park, Eden, Lowell, Westfield, Troy and Newport. (Route 100 ends just six miles shy of the Canadian border and morphs into Route 105.)

Case in point: A teardrop-shaped pin on Google Maps marks the Vermont International Museum of Contemporary Art + Design, on the east side of Eden. There's no sign for it, but a right turn onto steep, dirt Earle Lane leads to a yellow house on a hillside littered with all manner of rural detritus.

Surprisingly, there's a doorbell. Pressing it summoned acclaimed artist Matt Neckers, who graciously led his two uninvited guests on a tour of his hardscrabble creative wonderland. The centerpiece — a retro camper— is a mobile art gallery filled with marvelous miniature installations. As in the unorthodox galleries of Marfa, Texas, the incongruity of it all enhances the viewer's delight.

Neckers happily provided directions to the next mind-blowing marvel that Edenites don't advertise. Visible over the treetops from some spots on Route 100, a light-colored deposit on Belvidere Mountain distinguishes it from every other peak in the area. A short drive to its eastern flank, on North Road, reveals why: Rising almost as high as the natural summit is an enormous pile of asbestos, the site of an abandoned mine that once operated 24-7 and employed more than 300 people. Now fenced off and guarded, it's an awesome, otherworldly sight.

Such natural resources and their capitalization have literally shaped this part of northern Vermont. In 1993, concerns about the dangers of asbestos led to the Eden mine's closure, which devastated the local economy. Today the industry du jour is a little farther up the road, where a ridgeline dotted with state-of-the-art industrial wind turbines looms above Lowell. You can't drive to them because the service road isn't marked, but you can observe their giant, graceful rotations from much of this stretch of state highway.

But first: long, lovely Lake Eden. Route 100 runs along the water, offering tantalizing glimpses and easy access to the town-run beach recreation area. Nonlocals pay $3 per day to park, picnic and swim.

At the northern end is the Mount Norris Scout Reservation, on 1,000 acres with its own private waterfront. There were signs of life in the main building — phones charging, half-eaten bagels — but it took a while to find camp director Alison Hampson. She explained that a weeklong coed scout camp was just wrapping up, and another group of kids would arrive on Sunday. The property is also available for outside rentals.

Climbing nearby Mount Norris is part of the weekly camp tradition, Hampson said of the property's namesake, but neither the trailhead nor the 3.8-mile, round-trip trail is well marked. We found it by following Hampson's detailed directions and got a beautiful, bird's-eye view of the lake and surrounding hills.

Back at sea level, Route 100 winds past fields and farms, big houses and ramshackle ones. Many of the Vermonters who reside here appear to be living off the land or trying to, whether they're extracting from it wood or stone, milk or maple. Similarly down-to-earth are the masonry, plumbing and heating, trucking, and electrical operations along the road, some of which are barely identified.

Only slightly harder to miss, the sign for Missisquoi Lanes & Lounge in Lowell advertises a vintage bowling alley in a nondescript, warehouse-style building that could just as well house dairy cattle or a brewery. Inside, I found two walls of lockers and Kevin Dumas and his wife cleaning the place. Dumas ran the business for 37 years, but his daughters officially own it now, he said proudly.

By this time, 3 p.m., I was hungry enough to ask Dumas if Missisquoi Lanes served food. It did, but I decided to hold out for Cajun's Snack Bar, a mile and a half up the road.

Open Wednesday through Sunday from 11 a.m. to 8 p.m., this seasonal eatery cooks up everything fried and delicious, including alligator and poutine, plus some healthy options. I ordered a lobster roll with hand-cut fries and a side salad; my S.O. got the whole belly clam dinner, breaking his rule never to order fried seafood out of view of the ocean. Everything tasted really good.

Aside from the no-frills general stores that serve travelers and residents, the only other sit-down restaurant I saw along this 42-mile stretch of Route 100 was the Junction Restaurant in Troy. Located at the intersection of Route 101, eight miles from Jay Peak, it serves lunch and dinner Wednesday through Sunday. Breakfast, too, on weekends.

Pro tip: If you're taking this drive on a Monday or Tuesday, bring provisions.

Thankful for the sustenance, we headed north again with full bellies in search of two other Google Maps locations that had caught my eye. One promised "discalced Carmelite nuns" on a back road between Lowell and Westfield; the other was the Monastery of the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

The Carmelites weren't home, or perhaps they just decided against coming out. ("Discalced" nuns eschew footwear.)

I tried harder at the monastery, which is right on Route 100 but set back from the road. We navigated the winding driveway, and I talked my way inside what turned out to be a concrete convent of 16 cloistered Benedictine nuns.

The woman on duty explained that she was not a sister but a religious layperson known as an "oblate." In response to my questions, she recommended a book called Of Bells and Cells: The World of Monks, Friars, Sisters and Nuns, about the different religious orders and how they worship. These Westfield nuns serve God with prayer. They host a public mass every day at 10 a.m.

I bought the book, which required summoning a nun who could operate the Square app on an iPhone. But a more intimate picture of the place emerged when a woman in a T-shirt and shorts appeared and asked me to accompany her to the visiting room.

Lisa Lucas of Pittsburgh was there to see her daughter, Mary Elizabeth, a 24-year-old novice. A floor-to-ceiling metal grate limited their communication to talking and grasping hands. So Lucas had introduced another sanctioned activity: making pasta. She asked me to take pictures of mother and daughter shaping cavatelli they would eat a few hours later, in separate dining rooms. Lucas seemed to be struggling with the ramifications of her daughter's life choice while accepting what she called "the will of God."

The oblate invited me to stay for vespers, but Newport called. As an alternative to attending the service, she suggested I stand outside, by the front door, and listen.

From the open windows came the sound of women's voices, strong and synchronous, like angels. The hills along this historic Vermont roadway may be rugged, and in some cases worn, but they are very much alive.

Pit Stops

- Vermont International Museum of Contemporary Art + Design, vtmocad.com

- Mount Norris, alltrails.com/trail/us/vermont/mount-norris

- Cajun's Snack Bar, cajunssnackbar.com

- Monastery of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, ihmwestfield.com

— P.R.

The original print version of this article was headlined "On the Road"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Culture, Route 100, Stamford, Jamaica, South Londonderry, Plymouth, Killington, Warren, Waitsfield, Morrisville, Hyde Park, Newport, Cajun’s Snack Bar, Mount Norris Scout Reservation, Mehuron's Supermarket, The Sweet Spot, Little River State Park, Green Mountain Club Headquarters, Oxbow Park, Lamoille Valley Rail Trail, Stone Revival, Honeypie, Stratton Mountain Resort, Main and Mountain Bar + Motel, 1A Coffee Roasters

About The Authors

Jordan Barry

Bio:

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Melissa Pasanen

Bio:

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Sally Pollak

Bio:

Sally Pollak is a staff writer at Seven Days. Her first newspaper job was compiling horse racing results at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Sally Pollak is a staff writer at Seven Days. Her first newspaper job was compiling horse racing results at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Paula Routly

Bio:

Paula Routly came to Vermont to attend Middlebury College. After graduation, she stayed and worked as a dance critic, arts writer, news reporter and editor before she started Seven Days newspaper with Pamela Polston in 1995. Routly covered arts news, then food, and, starting in 2008, focused her editorial energies on building the news side of the operation, for which she is a regular weekly editor. She conceptualized and managed the “Give and Take” special report on Vermont’s nonprofit sector, the “Our Towns” special issue and the yearlong “Hooked” series exploring Vermont’s opioid crisis. When she’s not editing stories, Routly runs the business side of Seven Days — overseeing finances, management and product development. She spearheaded the creation of the newspaper’s numerous ancillary publications and events such as Restaurant Week and the Vermont Tech Jam. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Paula Routly came to Vermont to attend Middlebury College. After graduation, she stayed and worked as a dance critic, arts writer, news reporter and editor before she started Seven Days newspaper with Pamela Polston in 1995. Routly covered arts news, then food, and, starting in 2008, focused her editorial energies on building the news side of the operation, for which she is a regular weekly editor. She conceptualized and managed the “Give and Take” special report on Vermont’s nonprofit sector, the “Our Towns” special issue and the yearlong “Hooked” series exploring Vermont’s opioid crisis. When she’s not editing stories, Routly runs the business side of Seven Days — overseeing finances, management and product development. She spearheaded the creation of the newspaper’s numerous ancillary publications and events such as Restaurant Week and the Vermont Tech Jam. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Latest in Culture

Related Locations

-

1A Coffee Roasters

- 123 W. Main St, Wilmington Brattleboro/Okemo Valley VT 05363

- 42.87144;-72.88139

-

802-265-0284

802-265-0284

- www.1acoffee.com…

-

Cajun’s Snack Bar

- 1594 Route 100, Lowell Northeast Kingdom VT 05847

- 44.81369;-72.44395

-

802-744-2002

802-744-2002

- www.cajunssnackbar.com

-

Green Mountain Club Headquarters

- 4711 Waterbury-Stowe Rd., Waterbury Center Mad River Valley/Waterbury VT 05677

- 44.37919;-72.72187

-

802-244-7037

802-244-7037

- www.greenmountainclub.org

-

Be the first to review this location!

-

Honeypie

- 8811 Route 30, Jamaica Brattleboro/Okemo Valley VT 05343

- 43.14601;-72.84121

-

802-548-4999

802-548-4999

- eatathoneypie.com…

-

Lamoille Valley Rail Trail

- n/a, St. Johnsbury to St. Albans Champlain Islands/Northwest VT 05478

- 0.00000;0.00000

-

802-229-0005

802-229-0005

- www.lvrt.org

-

Little River State Park

- 3444 Little River Rd., Waterbury Mad River Valley/Waterbury VT 05676

- 44.38984;-72.76728

-

802-244-7103

802-244-7103

- www.vtstateparks.com…

-

Main and Mountain Bar + Motel

- 112 Main St., Ludlow Brattleboro/Okemo Valley VT 05149

- 43.39585;-72.69804

-

802-242-1608

802-242-1608

- www.mainandmountain.com

-

Mehuron's Supermarket

- 5121 Main St., Suite 6, Waitsfield Mad River Valley/Waterbury VT 05673

- 44.18411;-72.83512

-

802-496-3700

802-496-3700

- www.mehurons.com

-

Mount Norris Scout Reservation

- 1 Boy Scout Camp Rd., Eden Mills Northeast Kingdom VT 05652

- 44.72982;-72.49209

-

802-635-7415

802-635-7415

-

Be the first to review this location!

-

Oxbow Park

- Portland St., Morrisville Stowe/Smuggs VT 05661

- 44.56366;-72.59841

-

802-498-8611

802-498-8611

-

Be the first to review this location!

-

Stone Revival

- 1354 Route 100, Stockbridge Rutland/Killington VT 05772

- 43.77647;-72.76880

-

802-746-8110

802-746-8110

- stonerevival.com

-

Be the first to review this location!

-

Stratton Mountain Resort

- 5 Village Lodge Rd., Stratton Brattleboro/Okemo Valley VT 05155

- 43.11382;-72.90509

-

Be the first to review this location!

-

The Sweet Spot

- 40 Bridge St., Waitsfield Mad River Valley/Waterbury VT 05673

- 44.18963;-72.82391

-

802-496-9199

802-496-9199

- www.thesweetspotvermont.com

Related Stories

Speaking of...

-

Waterbury: What to See, Do and Eat During the Eclipse

Mar 6, 2024 -

St. Johnsbury: What to See, Do and Eat During the Eclipse

Feb 10, 2024 -

Scrag & Roe Serves Global Plates in Waitsfield

Jan 23, 2024 -

Morrisville’s Lost Nation Brewing Charts a Path Through a Changing Beer Landscape

Jan 9, 2024 -

Backstory: Before She Could Work at Seven Days, Our Summer Intern Had to Learn to Drive

Dec 27, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: