Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Armed With a Video Camera, One Man Documents Crime and Disorder in Burlington

Published September 20, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated September 20, 2023 at 10:09 a.m.

It was only 10 a.m., but Wayne and Cheryl Savage were driving to Costco for ice cream sundaes on a humid Thursday in early September. Then the police scanner crackled to life, prompting Wayne to take a detour. The treat would have to wait.

"I'm gonna pull into City Hall Park," he said, whipping into a parking spot on College Street in downtown Burlington. "They've got an unresponsive person there."

"Oh, Lord," Cheryl said, because these calls happen all the time, including several already that morning.

Savage, a utility belt circling his generous waist, grabbed his handheld video camera, leaving his wife of 47 years in the air-conditioned comfort of their midsize SUV. He approached the cops clustered around the park bathroom, where a man inside had overdosed. Savage zoomed in on the man, who was being wheeled into an ambulance with an oxygen mask affixed to his face. Another overdose call came minutes later, sending two officers running across the park to Main Street, where a woman who had already been revived with Narcan five times that day was going under again. One of the officers said there must be a bad batch of drugs going around.

His job done, Savage started back toward his car. "As always, good seeing you, Wayne!" a police lieutenant called after him.

Burlington cops have seen a lot of Wayne Savage over the years. Queen City born and bred, he's been documenting emergency scenes for four decades, selling his film and video to news outlets for extra cash or just for the hell of it. Even at 66 years old, he can't resist when the scanner beckons.

And, oh, has it beckoned. Open drug use, gun violence and thefts downtown have generated widespread unease over public safety as the city contends with an opioid epidemic, a mental health crisis and a severe shortage of affordable housing. Savage, literally tethered to the mayhem by an ever-present earpiece connected to his scanner, has captured it all on film. What he doesn't sell to TV stations, he posts on social media.

His prolific dispatches and stark commentaries have sparked online debates about whether he is painting too grim a picture of the city. But Savage, who has a scrappy side, says his camera is merely capturing cold reality — and his neighbors need to wake up to it. His wife agrees.

"The way I see Wayne, he thinks he has a duty to show the public what's really going on," Cheryl said. "He's kinda like the man behind the camera with the truth."

'Wayne's Command Post'

click to enlarge

- Courtney Lamdin ©️ Seven Days

- Wayne Savage talking with Burlington firefighters at a crash scene

The tools of Savage's self-made trade are all accessible from his couch in the living room of his New North End home. A scanner announces one crisis after another, and battery chargers line a nearby shelf. A printout on the wall lists interstate mile marker numbers and their corresponding towns, a handy reference when a call comes in.

Cheryl calls the setup "Wayne's Command Post." He calls it necessary.

Savage discovered photography after taking a class as a sophomore at Burlington High School. He kept up with it after graduation as a newly minted Marine, snapping photos on deployments to Japan and South Korea. Back home, he got a job managing the bygone Abraham's Camera Center on the Church Street Marketplace.

Then, on a summer night in 1981, he took the picture that would launch thousands more. The Savages were eating dinner in their Pine Street apartment when they heard a crash. It was a motorcycle, and the driver was badly injured. Using a 35mm Nikon, Savage photographed the police and EMTs at the scene and donated the shots to the departments to use for training. They appreciated the help, Savage said, so he kept doing it.

Savage sold cameras by day and went to emergency calls at night. He didn't have a car at first, so he'd run to scenes lugging 50 pounds of equipment. His shoestring efforts paid off in 1987, when his photo of an arson fire at an abandoned waterfront grain mill made the front page of the Burlington Free Press. The exposure motivated him to keep going.

Savage had a number of odd jobs — entering invoices at a women's clothing store, painting lines on Vermont roads — and a part-time gig with Burlington's public works department actually helped his side hustle: He memorized the city street grid. He became a regular at scenes, often arriving before professional journalists did. He made a deal with the Free Press' then-chief photographer, Jym Wilson.

"[If] my film's better, he would use it," Savage said. "Most of the time, it was."

Savage won't reveal how much he's made stringing but did say the Free Press paid him a premium for big stories, particularly if they happened at odd hours — such as an early morning fire at Shelburne Farms that destroyed a historic dairy barn in 2016. That same year, he was the first photographer to respond when a wrong-way driver killed five teenagers in a head-on crash on Interstate 89 in Williston.

"If the sun was down and he was calling me, something bad had happened," said Ryan Mercer, the Free Press chief photographer from 2006 to 2019.

Savage has been known to cut dinner short when the tones sound, preferring to feed his hobby rather than himself. He once tried to leave a hospital where he was being treated for a burst appendix to snap photos.

Cheryl is used to it by now and even sleeps through the scanner. Friends have said she needs to rein Wayne in, but she shrugs it off. Wayne supported her work — a three-decade career as head housekeeper at two hotels in Burlington — so she supports him.

But Cheryl does worry that some calls are dangerous. Last year in Burlington, gunfire was reported two dozen times. Savage, who was recovering from major surgery, responded to each call.

"I've been doing it for so long, I can't get it out of my system," he said — "even though I'm trying."

'Bit of a Prophet'

Years on the beat have sharpened Savage's skills. As he drives to a scene, he plots where he'll park so he can get the goods and get gone. When he arrives, he composes his shots so they're made for TV. Vertically oriented video, for instance, is a no-no.

He's also not afraid to get close-ups. One afternoon in July, a five-car crash brought traffic to a standstill on Main Street. Savage took advantage of the relative calm to get into the right position.

His Sony video camera strapped to his hand, he stepped off the sidewalk toward a silver Chrysler, its rear door crumpled like used aluminum foil. The driver shot him a look, undoubtedly curious about the bearded man wearing an earpiece and pink Crocs, but the police officer talking with her paid him no mind.

Savage steadied his camera, breathing carefully, as he'd learned to do while firing his rifle as a young Marine, and walked past the fire trucks to capture the scene in short bursts: an older woman on a stretcher, making a phone call; a blue Honda in the wrong travel lane, its front end buried in a pickup truck's bumper; a firefighter sweeping shattered glass.

"If you're good with the camera and know what you're doing," Savage said, "you can tell the story without having to say a single word."

First responders, including Police Chief Jon Murad and deputy fire Chief Derek Libby, praise Savage for his dedication — and timeliness.

"He's a bit of a prophet," one police officer at an overdose scene said. "He always shows up a minute after we get there. I don't know how he does it."

Savage's subjects, however, aren't so charmed by his savvy. In a video from earlier this year, a man who had been stabbed in the neck was being led to an ambulance when he noticed the camera. One hand stanching his wound, he flipped off Savage with the other.

Sometimes, Savage aggravates such conflicts. One June afternoon, he pulled up to a known drug house on lower Church Street just as police were making an arrest. A man yelled at him from the front stoop.

"Is that WCAX with a fake-ass camera?" the man said, approaching him. "What's your name? How is that you can record me and I can't know your fuckin' name?"

The man followed Savage to his truck and kept heckling him, even after officers explained that Savage had the right to film from a public sidewalk.

Savage could have just stayed quiet. But he didn't.

"Can't fix stupid in this city, can ya?" he shouted, then rolled up the window and drove away.

'Documenting Real Life'

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Wayne Savage

- A fire on North Winooski Avenue in Burlington in the 1980s

Savage starts most mornings with a stroll around his neighborhood.

He checks on the elderly woman who calls him "Angel" because he helps her around the house. He knocks on the window at a home daycare, spinning the kids inside into a frenzy. "Wayne, Wayne, Wayne!" they chant, offering him plastic food from their play sets.

It's a close-knit community, and Savage doesn't want his address published, lest the criminals he films read it in the newspaper.

After decades listening to a police scanner, it's not surprising that Savage has a heightened, if not distorted, sense of danger. He gets frustrated that not everyone shares it.

In recent weeks, Savage has fired off angry emails to WCAX for not running his footage of homeless encampments or people overdosing in public spaces. Instead of considering that the station may have limited funds for freelancers — which is how news director Roger Garrity explains the situation — Savage charges that the "mainstream media" is hiding the truth.

So he found another outlet that doesn't filter his content: a New North End neighborhood Facebook group of 1,900 members, in which he's one of the most prolific contributors.

Some people have complained that videos of crime and disorder downtown aren't relevant to the New North End. Others say the sheer number of Savage's posts creates a false impression that Burlington is dangerous. "I've strongly considered leaving the group because of them," one woman wrote.

A photo of a homeless encampment at Leddy Park that shows the faces of its habitants proved particularly controversial. Some group members said Savage was exploiting people who need help. In a different post, someone suggested he volunteer for a charity. Savage replied that he does, every weekend, at the New North End Food Pantry. He tells his haters to block him.

The group's administrator, Evan Litwin, said he thinks Savage is providing a public service. He pointed to a series of photos Savage posted earlier this month of police officers in pursuit of Eric Edson, a suspect in an armed robbery — the first leg of what would be a weeklong manhunt. Word got out that Savage had the scoop, and nearly 100 people requested to join the Facebook page. Police didn't issue a press release about the incident until late that night.

"Ultimately, what he's doing is documenting real life, real experiences, in real time," Litwin said. "If anything comes out of this, it's that we're having real and difficult conversations."

Savage's motives are twofold. He likes to inform his community, sure, but he also wants to drum up support for the police force, which is slowly rebuilding after a council vote three years ago reduced its size through attrition. He thinks people don't understand the burden the drug crisis has placed on first responders.

"These bleeding hearts [are] making excuses for what these people are doing," he said of people with substance-use disorder, though he wouldn't use that term. "People need to wake up and see what's going on."

After leaving City Hall Park, the Savages made it to Costco without incident. They said hello to a neighbor who was handing out samples of Greek yogurt and wandered to the food court.

Later that day, Savage would see his footage on the news and hear at least four more overdose calls on the scanner. But for the moment, the radio was relatively quiet, allowing Savage to reflect on how chasing sirens has hardened him. He's considered leaving Burlington, maybe for a place like North Carolina.

"I would bet he'd do the same thing down there," Cheryl said, between bites of strawberry ice cream. Her husband said he didn't think so; he wouldn't know the area.

"You'd get to know it," Cheryl said. "I don't think it's out of your blood, ever."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Wayne's World | Armed with a video camera, one man documents crime and disorder in Burlington"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Crime, Burlington, Wayne Savage, Cheryl Savage

More By This Author

About The Author

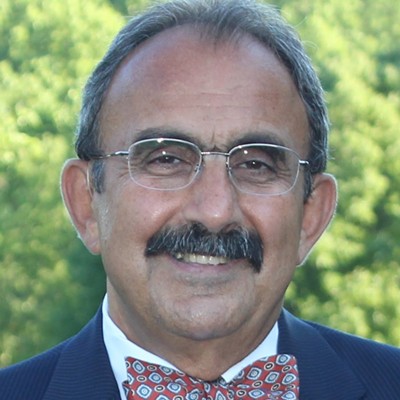

Courtney Lamdin

Bio:

Courtney Lamdin is a news reporter at Seven Days; she covers Burlington. She was previously executive editor of the Milton Independent, Colchester Sun and Essex Reporter.

Courtney Lamdin is a news reporter at Seven Days; she covers Burlington. She was previously executive editor of the Milton Independent, Colchester Sun and Essex Reporter.

Speaking of...

-

Queen City Café’s Biscuits Are Hot at Burlington's Coal Collective

May 7, 2024 -

Abbey Duke Replaces Emma Mulvaney-Stanak in Legislature

May 6, 2024 -

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate

May 1, 2024 -

Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help

May 1, 2024 -

Reinvented Deep City Brings Penny Cluse Café's Beloved Brunch Back to Burlington

Apr 30, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using Banned Pesticide Business

- 2. City to Sell Church Street Office Building to Burlington Telecom News

- 3. Independent Schools Rebuff School Districts' Request for a Tuition Break Education

- 4. Abbey Duke Replaces Emma Mulvaney-Stanak in Legislature News

- 5. Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Heads to Gov. Scott's Desk News

- 6. Renewable Energy Bill Heads to Governor's Desk News

- 7. Bernie Sanders to Run for Reelection to the U.S. Senate Politics

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 4. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 5. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 6. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis