Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Gardener’s Supply and Intervale Center Founder Will Raap Tackles an Ambitious Farm Project

Published May 4, 2022 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated May 12, 2022 at 10:18 a.m.

Will Raap has questions. "I'm gonna sorta use the Socratic method," he began, sitting in a conference room deep in a barn at Charlotte's former Nordic Farm.

"Oh, shit," responded Shelburne-based investment adviser Frank Koster with a grin.

"This is a failed dairy," Raap said energetically, a shock of white hair flopping above pale blue-gray eyes. "Why did dairies fail, do you think, in Vermont?"

Koster offered several reasons, including lack of scale in a low-margin, commodity business.

"OK," Raap continued, "what do you think the implications have been for the working landscape?"

And with that, their discussion on a recent April afternoon was off and running.

Such professorial interrogation is familiar to Raap's family, friends and colleagues. Constant questioning and the embrace of big ideas have been hallmarks of his work over the last 40 years. During that time, the entrepreneur has literally changed Chittenden County's landscape, and his influence has rippled across the state and beyond.

Raap founded Gardener's Supply, a now-employee-owned Burlington-based company with a second store in Williston — plus two more in New Hampshire and Massachusetts — and a robust mail-order business. COVID-19 propelled annual sales to $100 million worth of gardening gear to a local and national market. He also started the nonprofit Intervale Center, which has spawned dozens of Vermont farms and informed food and farming projects worldwide.

"Will is a leader, a visionary, what you would call 'influence maker' and somebody who really is connected to what land use and agriculture is all about in Vermont," said Roger Allbee, a former secretary of the state's Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets.

Now, at age 73, Raap has a new project, a reboot of Nordic Farm, the high-profile, hilltop former dairy on Route 7 in Charlotte. His ambitious goal for this venture: nothing less than demonstrating a new path forward for Vermont agriculture.

On the property's 583 acres, Raap hopes to build a collective of profitable and environmentally sustainable farm businesses. It's the kind of model, he claims, that could be replicated on other defunct dairy farms.

In December, Raap bought Nordic's assets for $3.4 million, including the equipment previously owned by Peterson Quality Malt, which malted grain grown on the farm to supply Vermont's many craft brewers and distillers. He also inherited a small on-site vegetable farm and a handful of tenant leases, including a flower farm, a shrimp aquaculture operation, a bakery and a beer aging facility.

Raap has renamed the enterprise Earthkeep Farmcommon. It's a big name to match a grand plan, but that's nothing new for Raap. He does not shy away from asking big questions and then puts everything he has into building answers.

"Will always starts with solving a problem, and it's never 'That's not gonna work; there are too many problems in the way.' It's 'Let's figure out how to get there,'" said longtime Intervale Center executive director Travis Marcotte. "There's a force that is Will. Even if people don't want to see something yet, it doesn't really deter him."

An early believer in employee-owned businesses, Raap brought on his colleagues as co-owners soon after founding Gardener's Supply. They are now 260 strong. Fellow Vermont entrepreneur Alan Newman worked closely with Raap at the company's start. Long before business culture became a catchphrase, Newman recalled, "Will asked, 'Why can't we bring our values and our culture into the business like we would in any other situation?'"

While growing his young company, Raap started the Intervale Foundation (later changed to Center), spearheading the transformation of Burlington's de facto city dump into a thriving agricultural and recreation hub. The nonprofit has incubated dozens of farms, advised hundreds more, expanded access to local food and inspired projects around the world.

In creating the center, Raap sought the answer to yet another big question, as he wrote to the Burlington Free Press in 1989: "How can farming compete when our tax system, our banks and our political leaders guide us to see flat, fertile land in terms of its potential for development, instead of for food production?"

A prolific investor and collaborator, Raap has learned, too, from endeavors with mixed results. He played a critical role in building the South Village development in South Burlington. It was intended to demonstrate a new approach to suburban housing that gave priority to open space, agriculture and community over asphalt and fences.

The development changed owners due to the Great Recession, and Raap laments that housing built since then has not stayed true to the original goals. Nevertheless, the neighborhood was among the first in Vermont with a virtual, net-metered solar array, and it continues to host a farm. (See "Root to Rise")

Raap does recognize that in order to reach the finish line, he sometimes has to give a little. "He knows when to change, when not to change and how to make things move forward," Allbee, the former ag secretary, said.

And, Allbee added, Raap has largely managed to do this "without pissing people off."

That skill will be critical to the success of Earthkeep Farmcommon. Indeed, all of Raap's experience and charisma will be required to meet the needs of multiple businesses, raise money and navigate a thicket of potential permitting hurdles.

With Earthkeep, Raap aims to demonstrate "a new way to be a farm." It will involve a cluster of collaborative, valued-added agricultural food and beverage operations that share acreage and infrastructure.

He asserts that the model will provide a good living for farmers and reward them for farming in ways that help combat the climate crisis. The regenerative practices include managing land so that it sinks more carbon and reduces agriculture's impact on the watershed, as well as on-farm renewable-energy projects.

Raap envisions the involvement of University of Vermont researchers and nonprofits that will help prove the project's worth and spread the gospel. They will be based in the farm's century-old white-and-red barn, for which he will soon launch a $5 million restoration campaign.

In his recent conversation with Koster, Raap ended with the big question — and formidable task — that he is taking on: "How can Earthkeep be a catalyst for the future of agriculture?"

After more than an hour of animated discourse, Raap sank back in his chair and said, "I'm tired."

Urgency and Dark Days

Raap had quadruple bypass heart surgery last July. Lynette Raap, his wife of almost 45 years, said that two days later he was back on email. "He told me, 'I want to go out spent and burned up and contributing to the max,'" she recalled.

Lynette said that doctors expect new heart plumbing like her husband's to work for about a decade. "I find it actually kind of refreshing," Raap said of the deadline. "There's an urgency about me — and there's an urgency about what we're trying to do."

When Raap told Newman about his Charlotte plans, Newman remembered saying, "What the hell are you doing, boy? This is a 20-year project."

"Taking on Earthkeep is an absurdity at my age," Raap acknowledged. But, he added, "People think I can get stuff done. I think I have an obligation to use that."

Time and again, Newman said, he has seen Raap set his sights on a big goal, communicate it in a way that people can invest in and then form the right partnerships to get it done. The two have not always gotten along, but even during rocky times, Raap is unfailingly fair, Newman said: "I've never seen him dig in on what's best for him."

Early on at Gardener's Supply, Cindy Turcot, now CEO and president, was working her way up from data entry. Raap wanted to give her a raise that the cash-strapped startup could not afford. "I remember very vividly him taking a pay cut so that I could get an increase," Turcot said. "That speaks volumes to who Will was and is."

Turcot half-jokes that she has often had to remind herself of things like that when she's had to deflect Raap's incessant avalanche of ideas. "He pushes hard. That's who he is," Turcot said. "But that's how he made the difference."

Julie Rubaud, now owner of Red Wagon Plants in Hinesburg, is one of many successful farmers who started out in the Intervale; in the early '90s, she served on the nonprofit's board. Raap "juggled a lot of personalities to make the Intervale work," Rubaud said. One time, Raap pulled her aside and said, "Hey, when you're here at the board meeting, you have to think like a board member, not like an anarchist farmer," Rubaud recalled with a chuckle.

Like a perpetual-motion machine, Raap feeds off the energy he generates. The toughest moments of his career, he acknowledged with some prompting from his wife, have occurred when he lost that sense of forward motion. Twice when Gardener's Supply struggled financially, Lynette said, Raap experienced serious periods of depression.

During the summer of 1992, after the recession obliged the company to lay off about 10 percent of its workforce, his daughter Kelsy was 8. She recalled the shock of seeing her dad "breaking down in a rocking chair and just bawling." Her father was sad for the company and for the employees, her parents explained.

"Progress feeds progress," Raap reflected to Seven Days. "When the world says no, no, no, how do you say yes? The answer is, sometimes you don't. Sometimes you get stuck."

Beyond feeling that he had let down his coworkers, "I was hitting the dead end of what I thought my reason for being was," Raap said. "Our mission as a business was to help people garden the right way so [they] could take care of the Earth."

He was also investing most of the company's profit into the Intervale nonprofit. "My potential to be effective in the world was about Gardener's Supply," Raap said. "That was my fuel."

His darkest days, he added, were when he couldn't see a way to make a difference.

Stakeholders, Not Shareholders

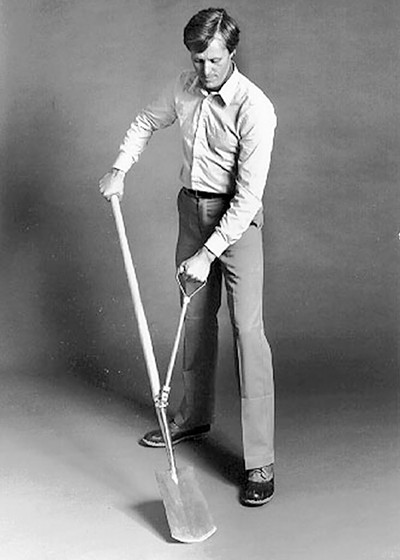

- Courtesy

- Will Raap in 2009 when Gardener's Supply became 100 percent employee-owned

At the Williston Gardener's Supply store on April 14, colorful hanging baskets and potted herbs provided cheery props for a video shoot — even if it was still a little early for outdoor planting in Vermont. Representatives from the Employee Ownership Foundation, a national nonprofit, were there to interview Raap.

Standing in front of spotlights, Raap was about to expound on why he chose employee ownership for his company. But the host started by asking if he had gardened growing up and how it had led to his career.

In Fremont, Calif., Raap's first job as a child was delivering eggs by bicycle, and his second was growing vegetables, Raap replied. Weeding was no fun, he conceded, but as he grew up, Raap was drawn to "working with nature and being a steward of nature."

Later, at the University of California, Berkeley, he earned a combined master's degree in business and urban planning. On the business school side, he explained to his interviewer, it was all about making profit for shareholders. The urban planners were focused on building spaces that worked for what they called stakeholders: "the community, the environment, the birds," Raap said.

He believed that business could be harnessed for the good of all. "Business is the most powerful force in the world," Raap said on camera. But to have a positive impact, "You have to know why you're doing what you're doing in business."

Raap pursued an employee-ownership structure early on, not as a retirement strategy, as many companies do. Rather, he explained, "The general idea of giving people a say in things and an ownership stake in things just makes sense."

Raap recounted how Home Depot approached him in 1999 about buying Gardener's Supply. Saying no was easy. "We never set out to only sell it to the highest bidder," he said.

The day after the video shoot, Raap sat down with Seven Days at the big round dining room table in the family's comfortable but unpretentious Shelburne home. He shared a formative childhood memory from his East Bay hometown: the 1962 construction of a General Motors plant. "I watched the cherry orchard behind our house and the apricot orchard in front of our house go down for housing," Raap said.

That plant now produces Teslas in the middle of Silicon Valley, a region that once blossomed with agriculture. "Now it's all been paved over," he said.

After grad school, Raap headed to Europe to explore ways to balance growth with human well-being.

In 1976, Raap landed at the alternative community of Findhorn in northern Scotland. Characteristically, he sought the answer to a question: "How do we get people living together and designing places together and eating together and growing food together?" And equally important, Raap remembered asking, "What's the economy of that place?"

At Findhorn, Raap met another American looking for answers — the woman who would become his wife. "I was a spiritual seeker," Lynette said. "[Will's] was an intellectual curiosity." The two married six months later, on the summer solstice of 1977.

When Lynette's father became sick, the couple returned to Old Greenwich, Conn., where Raap took a job at the nearby outpost of Garden Way, a Vermont mail-order garden products company. "I liked what they were doing, which was back to the land, alternative energy, grow your own food," he said.

But Connecticut did not suit the couple, and Raap landed a position at his employer's Vermont headquarters.

"I came to Vermont because it seemed special by operating at a community scale, believing working landscapes are a high priority and nature matters," he said. Raap also appreciated what he called the state's "independent thinking and action."

'The Power of One'

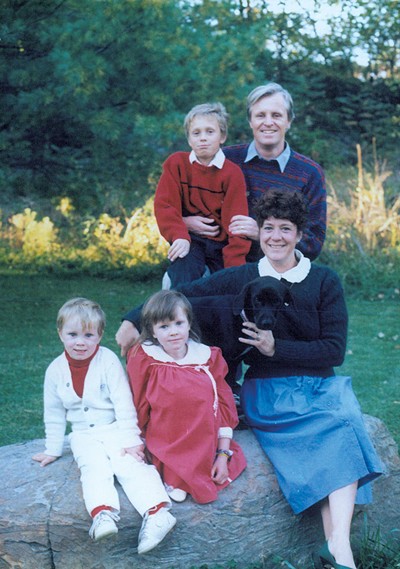

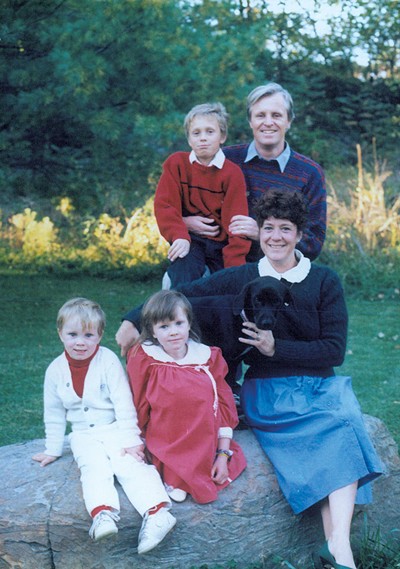

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- Will and Lynette Raap with their children (from left) Addison, Kelsy and Dylan in 1990

With their eldest child in tow, the Raaps arrived in Burlington in 1981 on the day that Bernie Sanders was elected mayor.

A year later, Raap was on loan from Garden Way to the company's nonprofit community gardening arm, Gardens for All. He was sitting in his first board meeting next to Garden Way founder Lyman Wood, when Wood and all the Vermont employees were abruptly fired in a corporate takeover. Raap launched Gardener's Supply the following year so that the family could stay in Vermont.

From Wood, Raap had learned about both mail order and gardening products. He had also absorbed the lesson that a for-profit company could support a nonprofit, which he would replicate when he founded the Intervale Foundation in 1987.

At Garden Way, the aspiring entrepreneur had experienced how business could be a force for positive change — and how a narrow focus on profit could halt that momentum in its tracks. Raap was determined to do things differently.

From the beginning, he invested equally in building the business and building a company that supported and motivated its employees. One early effort involved a workshop hosted by a young motivational speaker, Tony Robbins, in which participants learned how to overcome their fears. As a final test, they walked over hot coals.

Raap wanted to create a culture of big thinkers. "Business is oftentimes about, 'Oh, shit, I can't do that. That's not possible,'" he said. Faced with a bed of red-hot coals, the natural response is exactly that. Yet Raap made it over the coals without getting burned. The ability to control your fear and do something that seems impossible "totally lives with you," he said.

Within two years, Gardener's Supply was generating $3 million in annual sales and had 25 employees. Lynette said that, especially in the early years, her husband worked incessantly, surviving on as little as three hours of sleep a night. His kids can still recite his office phone number by heart, because they called it so many times to ask when he'd be home for supper.

When the family did manage to get away, it was usually to Costa Rica, where Lynette has family ties. Even there, Raap eventually started some projects to support sustainable food and forest redevelopment.

"Will cannot go on vacation," Lynette said. "He has to have a project."

His three now-grown children described the constant volley of questions that propelled conversation around the family dinner table. "Can either of you remember a dinner where we didn't talk business?" Dylan asked his two younger siblings in a conversation at his Burlington CBD company, Upstate Elevator Supply, where all three work.

"We idolized entrepreneurship in our household," Kelsy said. "We revered people who are willing to do whatever it takes, however long it takes, to make their dreams into a reality."

Addison, the youngest, said he's often wanted to beg his father, "Can't you just slow down? Do you need to have all of these irons in the fire? Can you stop inventing for a minute?"

But the three remember their dad helping them with homework and coaching their soccer teams. He pulled them into his world. They weeded and planted at the Intervale. Kelsy and Addison became young entrepreneurs when their father made them the subcontractor of a new product, Mole Control. It involved mixing and bottling a castor-oil-and-dish-soap blend to sell to Gardener's Supply.

The pair also recalled one Christmas during elementary school when their father came home announcing that the company had had its best sales week ever. Raap took the kids to a toy store and gave them equal amounts of money to spend on themselves and for toys to give away. It was a memorable lesson in "what sharing blessings felt like," Kelsy said.

No one is more tickled than Raap that his offspring work together — he often sports Upstate Elevator Supply-branded clothing. Dylan grew the business from the success of Green State Gardener, which he originally incubated, Silicon Valley-style, as a "skunkworks" project at Gardener's Supply.

Dylan believes it was the first CBD retailer in Vermont; it's now poised to hold one of Burlington's first retail cannabis licenses.

click to enlarge

- Daria Bishop

- From left: Addison, Kelsy and Dylan Raap at Upstate Elevator Supply and Green State Gardener in Burlington

Green State Gardener was born after Gardener's Supply decided against marketing explicitly to cannabis home growers, despite Raap's urging. To help manage her boss' constant brainstorms, Turcot had set up a founder's fund for Raap to use at his discretion for ideas he felt compelled to pursue on his own.

Even after stepping back from day-to-day operations at Gardener's Supply just over a decade ago, Raap served as chair of the company's board and "chief disrupter," as he put it, not joking.

In April 2021, the company employee-ownership program paid off its shareholder note to Raap in full. He then stepped down as board chair but remains a board member. Though others held leadership roles at Gardener's Supply, Raap said that until last spring he felt ultimately accountable for the company's trajectory.

"He hates when I call it this, but it's the power of one," said Turcot, referring to the theory that one person's action can change the lives of many.

Wasteland to Cornucopia

Contrary to many published accounts, Raap did not discover the Intervale when police called to tell him his stolen car had been found there in 1984. The theft did happen, but the Raaps were already familiar with the Intervale because they had a community garden plot there.

Crossing the railroad tracks to reclaim his car did open Raap's eyes to other parts of the Intervale. Under hundreds of junked cars, thousands of tires and sewage, he saw the promise of something else in the historic, fertile floodplain.

"He decided, 'Holy shit, this is a great growing region here in the city of Burlington,'" Newman recalled. "'We could have a food basket here that feeds the city — how cool is that?'"

Raap's first step in late 1985 involved moving his young business into the Intervale site of an old McKenzie slaughterhouse. This was not a popular decision with everyone in the office. It's hard to imagine how different the Intervale was back then — most certainly not a cornucopia of organic vegetables, idyllic setting for food and music events, and network of year-round recreation trails.

Peter Clavelle worked closely with Raap, initially as Burlington's director of the Community & Economic Development Office and then as mayor. As a kid growing up in Winooski, Clavelle said of the Intervale, "[It] was not a place you would go unless you wanted to drink underage, do a drug deal, or dispose of a junk car, refrigerator or washing machine. It was a wasteland."

To be fair, it was also still home to the city's sole remaining dairy farm, owned by the legendary octogenarian Rena Calkins. She lived in the brick farmhouse that is now the Intervale Center's office.

Calkins' farm occupied about 187 acres, and befriending her was critical to realizing Raap's vision. According to Newman, "If you came by to talk to her, she aimed the shotgun at you. You had a choice: You could run, or you could hope to get her attention. Most people ran."

Raap didn't run. "He'd say, 'I'm going over to see Rena. If I'm not back in a half hour, send the ambulance,'" Newman said.

Gradually, Raap built a relationship with Calkins and her family. Over the years since, her heirs have sold and donated a combined 141 acres to the nonprofit.

"The idea of making [the Intervale] a productive part of our economy and our ecology made sense," Clavelle said. "How to get there was another question. The ownership was fragmented. The city was spreading sewage sludge on the property."

Raap took each challenge as it came, gathering supporters along the way like the Pied Piper. He had a way of seeding his enthusiasm in others, of convincing them that it was "a journey they wanted to take," Clavelle said.

Over the Intervale nonprofit's first decade or so, Gardener's Supply supported it. Lynette, who worked for the company as a buyer, remembered being troubled by high product markups. "'You don't understand your husband,'" she recalled her manager saying. "'We have to make enough money so we can give it away.'"

Since then, Raap has guided the Intervale Center to self-sufficiency with the creation of for-profit projects under the nonprofit umbrella. One is a conservation nursery that grows and sells native plants for restoration efforts. Another is the Intervale Food Hub, which consolidates food from 60 to 70 Vermont farms and other producers for delivery to customers, food service accounts and the charitable food system. The hub generates about $1 million in annual revenue, of which about 70 percent goes back to producers.

Some critics quibble with a nonprofit entering the business sector, but Raap sees that as an artificial wall. The profitable innovations support the Intervale's broader mission. Their revenue not only funds efforts such as a free farm share for eligible community members, the programs also help protect the environment and expand markets for local food producers.

Entrepreneurship, said Marcotte, is part of "the founding DNA of the Intervale Center."

Occasionally, Raap has had to concede defeat. His dream of capturing waste energy from the McNeil Generating Station in the Intervale landed a major federal grant only to sink under permitting challenges and lack of a significant power customer. Intervale Compost Products became a high-profile victim of its own success when it outgrew its space and ran up against Act 250 — though Raap pointed out that it lives on elsewhere as part of Chittenden Solid Waste District.

Innovation Zone

The specters of permitting and Act 250 hover over Raap's new project. Unsurprisingly, he's confident he can vanquish them.

On April 20, green rows of winter rye and barley snaked across some 180 acres of Earthkeep Farmcommon's softly rolling fields. Farm and land director Jacob Keszey explained that the grains are being grown with minimal tilling practices and will be malted on-site for sale to local brewers and distillers. Another 55 acres are in hay, and about seven are devoted to vegetables, hemp and flowers.

Pointing to an overgrown pasture, Keszey said sheep and goats would soon arrive to reclaim the field from invasive plants and add natural fertility. The animals would spread their manure on the hoof, so to speak.

Raap first considered buying Nordic Farm a few years ago, before it was purchased in 2018 by Andrew Peterson of Peterson Quality Malt and a small group of investors led by Jay Canning, founder of Westport Hospitality, which owns Hotel Vermont.

At the time, the deal was heralded as part of the next wave of Vermont agriculture. Vermont milk was in a perpetual slump, but Vermont beer, the market for Peterson's malted grain, was booming.

That promise did not pan out. It became increasingly clear, Canning said, that "as a group, including the operating partner" — by which he meant Peterson — "we weren't really qualified to scale up the business from a very small malt production business to a very large-scale production business."

When Raap originally looked at the property, he had been working with the Vermont Cannabis Collective, a group of entrepreneurs recommending ways that legal pot could benefit Vermont. His vision then was to develop a Vermont Botanical Commons, a place to grow a variety of plants, including cannabis, that could be used in food and health products, not just to deliver a high.

In early 2021, after Canning approached him, Raap revisited that option. But it turned out that federal funds helped conserve the Charlotte farm in 1997, and that precludes growing marijuana since it remains against federal law. Agricultural conservation also means that the land cannot be subdivided or sold for commercial activity other than farming.

Raap pondered how to put a 600-acre conserved farm to productive use. Commodity dairy was obviously out. Hemp had crashed. Grass-fed beef might work if the land made good pasture. The malting business could be revived, but he did not believe it could support the entire farm infrastructure.

click to enlarge

- Daria Bishop

- From left: Olya Virgalla, Scott Medellin, Marissa Swartley and Keir Schofield making baked goods at Slowfire Bakery

Instead, Raap took a lesson from the incubator model that had proven successful in the Intervale. He envisioned a dozen or so small agriculture-based enterprises. A few would be owned by Earthkeep, but the remainder would not. Raap began by learning about the malting business and the existing tenants: Clayton Floral, Sweet Sound Aquaculture, Slowfire Bakery and House of Fermentology, an offshoot of Burlington's Foam Brewers.

He also started courting new candidates. Hinesburg-based Shrubbly, which produces a line of carbonated, tart, fruity drinks, signed on to grow berries and make its base shrub on the farm as it expands. Vermont Compost of Montpelier is strongly considering a satellite compost operation at Earthkeep, with chickens to help break down food waste and produce eggs.

Other micro-enterprises might include a craft dairy grazing its small herd or flock and making cheese, or a mushroom farm in one of the dark interior rooms of the barn.

"We support them. We incubate them. We accelerate them," Raap said. "Some of those will graduate out of here. Some of those will be models of things we can do on other large dairies that have failed."

In July, Raap and a small team took over running the operation with an option to buy. He rehired two former Peterson Quality Malt employees under a new business called Vermont Malthouse. Raap asked to join the team on weekly calls with a malting consultant to help him better understand their needs.

Raap also had to finish dispatching the rats — "thousands, maybe tens of thousands of rats," he said. Though they stayed largely out of the modern milking barn, the rodents had taken over other parts of the property, attracted by unprotected sacks of barley.

Canning had begun the rat eradication project. Raap's team completed it with the help of a pest-control expert. "Did you know there's a king rat?" Raap asked. "If you can get the alpha rat, you can control the whole nest."

The new team also started tackling another pesky problem, the project's potential Achilles' heel.

For a group of food and beverage businesses to operate on the property, Earthkeep must meet the Town of Charlotte's understanding of what a farm is allowed to do. Otherwise, Raap's project could run into intractable permitting or zoning hurdles.

A key part of his strategy relies on a 2018 state law known as Act 143. The law was written to help farmers run on-farm, agriculture-related enterprises that towns might otherwise consider to be commercial or manufacturing activities. Depending on the town, the latter may not be permitted on farms.

Among the supported activities outlined by Act 143 are storage, preparation and sale of processed farm products, as long as a majority of the farm's total sales are from agricultural products produced on the farm. The ingredients in those products must also be principally grown on the farm, although details of that requirement are currently under review in the Vermont legislature.

Earthkeep's malthouse, for example, likely meets the majority threshold since it sources much of its grain from the surrounding acreage. The shrimp farm, raising and selling whole, unprocessed shrimp, has no issues. Dicier, for now, are the beer aging facility and the bakery. Both use many Vermont ingredients but not a significant quantity raised on the farm — although there are plans to do so.

Raap believes the solution is for all the businesses to meet the guidelines collectively, rather than individually. It may work. The Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets recently determined that the newly formed Earthkeep Farmers Collective constitutes a farm and qualifies to use the property for processing as well as growing. But the final decision lies with the Town of Charlotte.

"If we manage Act 143 successfully," Raap said, "it could result in a force for innovation in Vermont that is congruent with what Vermont has always done best: people working together."

Much remains to be hammered out. The Town of Charlotte is taking a wait-and-see approach, according to town planner Larry Lewack. "We want them to succeed. We want the farmstead to be a thriving example of Charlotte's diversified agricultural operations," he said.

Lewack did note that he would like the Earthkeep team to communicate more with the town about its plans. At minimum, he said, a farm incubator and showcase for Vermont's agricultural future will likely draw enough traffic to warrant more parking, and possibly added turning lanes on Route 7.

The Really Big Idea

click to enlarge

- Daria Bishop

- Jamie Cohen and Jacob Keszey (right) weeding at the Earthkeep Farmcommon greenhouse

Even if Raap can successfully deploy what Dylan describes as his dad's "combination of irrational exuberance and indomitable will [to] brute-force super-complex ideas into reality," the question remains how replicable Earthkeep will be.

Ultimately, Raap's goal is to create something that goes beyond the iconic Charlotte farm's borders, just as the Intervale helped cultivate a new generation of organic farmers and inspired food-system change.

Ellen Kahler is executive director of Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, which coordinates the Vermont Farm to Plate Network. She and her team frequently host guests from afar, including a recent group from South Korea that she brought to the Intervale.

"It really started with the initial seed that Will planted," Kahler said, "and has grown into something that's, quite frankly, world-renowned."

But Kahler cautioned that Raap's new project starts with a higher bar — and that cloning Earthkeep might also require cloning Raap. Many of the pieces, especially research-proven agricultural practices, should be transferrable. But, Kahler said, "It takes a lot of money and vision and leadership to secure that kind of a land base and fund it appropriately to be able to do these kinds of things."

Rachel Nevitt and David Zuckerman of Full Moon Farm have similar concerns. The married couple, who courted in the Intervale, credit Raap's incubator program for helping their farm graduate to its own land in Hinesburg in 2008.

"Will Raap is definitely an idea man, and he does a lot," Nevitt said, "but I do wonder about the overall resiliency that [Earthkeep] is creating in our food system."

Her husband worries that the project sets unattainable standards for farmers without the same deep-pocketed support. "It doesn't seem to function within the economic realities of farming," Zuckerman said.

Raap is already working on an answer to that.

"Have I told you about my really big idea?" he asked with excitement during his dialogue with Koster, the investment adviser, in the Earthkeep conference room.

Just the week before, Raap said, he'd secured $150,000 from a private foundation to explore how to develop a capital fund that would support farms and other enterprises that invest in the environment.

Vermont, Raap said, is uniquely positioned to jump on the growing interest in investment that, more than just rewarding financial returns, also values, for example, farming practices that protect and rebuild the Earth.

"We can fund farmers to be good farmers," Raap said. "Let's have Vermont lead that parade."

Correction, May 5, 2022, A previous version of this story misrepresented Rachel Nevitt and David Zuckerman's concerns about value-added products and has been corrected for clarity.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Growing Green"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Melissa Pasanen

Bio:

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

More By This Author

Latest in Business

Speaking of...

-

Spring Foraging in Burlington’s Intervale Beyond Ramps and Fiddleheads

May 2, 2023 -

High-Profile Charlotte Farm, Site of Entrepreneur Will Raap’s Final Ambitious Project, Is for Sale

Apr 13, 2023 -

Intervale Center Ends Its Food Hub Consumer Program

Jan 24, 2023 -

'Visionary' Vermont Entrepreneur Will Raap Dies at 73

Dec 13, 2022 -

With Nordic Nite Out, Charlotte Agriculture Hub Launches Weekly Market

Sep 7, 2021 - More »

find, follow, fan us: