Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Motel Owners Are Withholding Security Deposits Meant to Benefit Homeless Tenants

Published March 22, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated April 11, 2023 at 2:29 p.m.

click to enlarge

- Zachary P. Stephens

- Former hotel resident Michael Hutchins outside the Brattleboro building where he lives

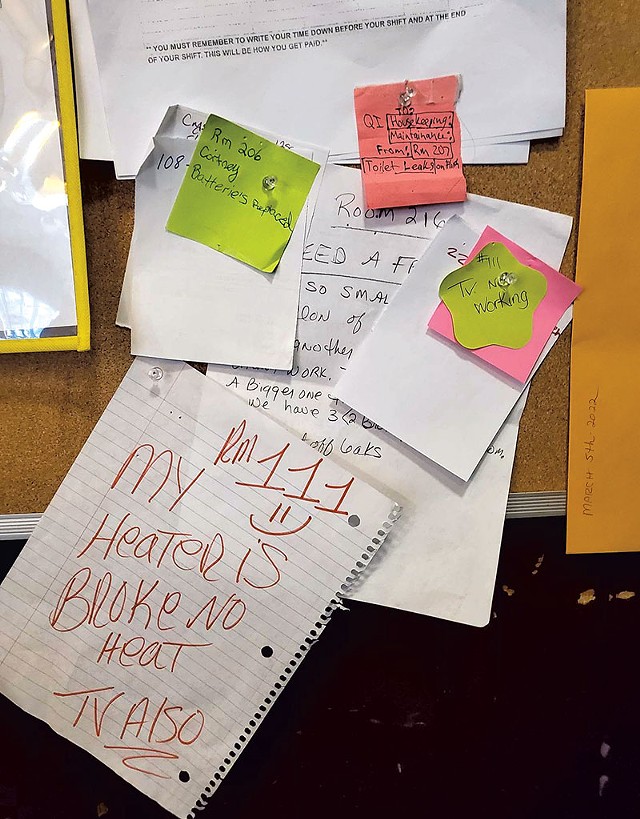

When Brenda Ouellette moved into Room 107 at the Brattleboro Quality Inn last fall, the paint was peeling, the bathroom was rife with black mold, and the sink was separating from the wall. These weren't the worst conditions Ouellette had seen at the Quality Inn, where she'd been living since January 2022 through a state program that assists Vermonters experiencing homelessness by placing them temporarily in motels. Her fellow guests, all of whom were in the program, regularly went without heat or a working microwave, the only cooking appliance allowed in their rooms, Ouellette said. Ouellette, who also worked at the hotel during her stay, said management often took weeks to respond to maintenance requests — if it responded at all.

On at least one occasion, Ouellette said, management told her to hide live wires above ceiling tiles in anticipation of a visit from the fire marshal. Toilets frequently backed up and overflowed; a Vermont Department of Health complaint filed by a social service worker in November 2022 alleged that many of the mattresses were stained with blood. Ouellette briefly lived in a room with such a bad bedbug infestation that she had to see a doctor for the bites. For these accommodations, the hotel was billing the state roughly $3,880 a month per room, almost triple the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Brattleboro.

In October, Ouellette was approved for a subsidized apartment in West Brattleboro. After two years of homelessness, she was relieved to finally have a place to call her own. "I thought, I don't have to worry about all the bullshit," Ouellette said.

For Ouellette and the roughly 1,730 other households enrolled in the program between July and October 2022, the state paid motels a $3,300 security deposit. Because of an agreement she'd signed with the Quality Inn, Ouellette knew she should be eligible to collect the deposit when she moved out in early November. Ouellette suffers from chronic health problems, and that money could have allowed her to buy a winter coat without skimping on other necessities, or get ahead on her rent in case she ended up in the hospital.

Ouellette said she took care to leave her room cleaner than she found it. She scrubbed the furniture with Simple Green, stripped her bed, vacuumed the carpet, scoured the mini fridge and microwave inside and out, wiped the grime and dust from the heater vents, and disinfected the bathroom. A hotel employee inspected her room, Ouellette said, and didn't note any problems. When Ouellette called the front desk the day after she moved out to see whether she'd forgotten anything, she said, she was told that someone else had already moved in.

But nearly five months later, Ouellette still hasn't gotten her security deposit, nor has the Quality Inn's owner, Anil Sachdev, returned her calls and texts. In December, Ouellette contacted Legal Services Vermont, a nonprofit that helps low-income Vermonters with civil issues; two months later, a Legal Services attorney, Mark Hengstler, sent Sachdev a letter ordering him to release Ouellette's security deposit or explain his reasons for withholding it within 10 days. Sachdev has not replied, and Ouellette is now preparing to sue him in civil court, because the state won't intervene. "I did everything right," Ouellette said. "The state knows this guy is robbing them of their money, and I don't understand why they're not jumping in to hold him accountable."

Sachdev did not respond to multiple attempts to arrange an interview. In reply to a text message last week, Sachdev wrote that he was in India, "with limited phone coverage." He didn't return a follow-up message, nor did he reply to a list of emailed questions. Seven Days attempted to reach him again on Monday, after one of his associates indicated he had returned, and got no response.

He told VTDigger.org that his staff members work to fix problems promptly, but he blamed residents for delaying repairs by insisting that motel staff give them notice before going into their rooms. He added that he'll have to invest heavily to make his properties suitable for tourists again when funding for the motel housing program runs out at the end of May.

Since March 2020, Vermont has spent upwards of $180 million to shelter more than 6,000 households in hotels. An infusion of federal aid during the pandemic allowed the state to transform a decades-old program that paid for motel rooms for unhoused Vermonters on the coldest winter nights into a provisional solution to twin crises: the state's dire housing shortage and its rising rate of homelessness, now the second-highest per capita in the country.

The security deposits represent a small fraction of Vermont's spending on the motel program, amounting to just under $6 million. But the state did little to prevent motel owners from exploiting its largesse, nor did it create any mechanisms to ensure that former residents would receive the funds that were meant to help them get on their feet.

Most of that cash, along with the rest of the money the state has poured into the motel program, has wound up in the hands of private business owners such as Sachdev, a principal in seven Vermont hotels whose chief source of revenue is unhoused, low-income guests. Since July, his properties have collectively brought in close to $20 million in monthly payments from the state, according to data from the Department for Children and Families, which administers the motel program. That equals roughly one-third of the department's total spending since April on the program, which encompasses more than 70 lodging establishments.

click to enlarge

- Zachary P. Stephens

- A young child looking through the window and tattered screens at the Quality Inn in Brattleboro

As affordable housing remains in critically short supply, the state has become increasingly dependent on motels to provide shelter for its growing unhoused population. In summer 2022, DCF revised the motel program to more closely resemble a rental arrangement, with a contract between owners and occupants that guaranteed three months of housing at a time, for up to 18 months. To encourage motels to participate, the state threw in an extra enticement: the $3,300 security deposits.

If residents leave the motel after less than four months, according to the contract, hotels are supposed to return the deposits to DCF, minus any damages. Residents who stay four months or longer are eligible to collect the deposits when they move out, as long as their rooms are in good condition.

These rules were intended to offer greater stability for long-term occupants, with a crucial caveat: Motel tenants would be exempt from renter protections under state law, a condition that was spelled out in the Budget Adjustment Act that year. The program guidelines explicitly state that DCF will not get involved in a security deposit dispute between a motel and a resident, nor does the department require motel owners to document their damage claims. DCF confirmed that it only tracks the $1.4 million in security deposits due back to the state. The remaining $4.3 million, ostensibly for people who leave the program, is being held entirely at the discretion of motel owners.

Hengstler, Ouellette's attorney, said DCF officials have been referring people with security deposit complaints to Legal Services. Taking a motel owner to court can present an enormous hurdle for a person who used the program, Hengstler said: "If I've been homeless and I'm exiting a motel, the moment I most need that $3,300 is the minute I step out the door."

Ouellette's Quality Inn room inspection form, which Hengstler shared with Seven Days, noted that "the cost of repairs can be adjusted towards [the] security deposit," without making a distinction between existing damages and damages caused by the occupant. That form, which came from the management of the Quality Inn, doesn't align with the program's stipulation that damage must have been caused by the tenant in order for a motel to withhold the deposit.

Since November, Hengstler has fielded two or three calls a week from former motel residents who say their security deposits have been wrongfully withheld; a substantial number of those calls, Hengstler said, have come from past occupants of Sachdev's properties, which include the Hilltop Inn in Berlin; the Cortina Inn, Quality Inn, Pine Tree Lodge and Econo Lodge in Rutland; and the Econo Lodge in Montpelier. The state hasn't had much luck getting its money back, either. As of mid-March, Sachdev's hotels still owed almost $310,000 of roughly $380,000 they received in deposits for guests who left after less than four months, according to data provided by DCF.

"Somebody like Anil is the product of the state's creation," Hengstler said. DCF, he contends, could have required motels to submit detailed damage claims, mandated that deposits be held in escrow and imposed sanctions on hotels for improperly withholding deposits. "It was a mistake to not create safeguards to get this money to people," he said. "And now that we all see that it's a mistake, I think that we should expect our government to acknowledge it and work to correct it. And that's not what's happening."

According to Hengstler, Mark Eley, who until recently served as director of the general assistance program at DCF, has acknowledged privately that Sachdev "doesn't follow the rules." "But his position appears to be, 'There's not much we can do about it. He's got rooms, and we need rooms.'" (Eley did not respond to questions about these remarks.)

In an interview in February, then-acting DCF commissioner Harry Chen said he was "concerned" about the motels' failure to return security deposits to former residents. In January, DCF sent letters to motel owners encouraging them to document damages, but beyond that, Chen maintained that the department had limited leverage. "The obvious challenge is that these motels don't have agreements with us," said Chen, who stepped down at the end of last month. "I don't know that we have another legal framework on which to do anything other than to put the landlords on notice."

To pay for the program, he explained, the state used funds from the federal Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which required a contract between a building owner and an occupant. The department saw no need to add guardrails to prevent motel owners from abusing the system, because "we weren't exactly sure that would necessarily be a challenge," said Katarina Lisaius, a senior adviser to the DCF commissioner. "So we're mitigating as best we can in real time."

On the whole, Chen said, the motel program has been an imperfect solution to a pressing problem; in deciding how to deal with owners who don't follow the rules, he suggested that the state has to carefully weigh the consequences. "We have people who are not being housed every day, because there aren't enough hotel rooms," he said. "So, you have to balance the need with the supply."

Some motel owners have taken full advantage of DCF's willingness to do business at practically any cost. Before the state imposed a monthly rate cap of $5,250 per room in September, the Bradford Motel was charging $8,000 a month for its rooms while occupants went without air conditioning, an amenity the owner offered only to "regular" paying guests, VTDigger recently reported. The owner told VTDigger that DCF officials encouraged her to name a price that would offset the risk she felt she was assuming by taking in state-funded guests, whom she largely blamed for the problems at the motel.

Between July and September 2022, the Vermont Department of Health received 20 complaints about unsafe and unsanitary conditions at motels in the program, ranging from bedbug-riddled sheets to a lack of heat and hot water for residents. In October, after months of warnings, the health department sanctioned the Colchester Quality Inn for failing to contain a raging bedbug infestation and capped the number of rooms it could rent through the state. During a February visit to Sachdev's Cortina Inn in Rutland, which has raked in more than $5.6 million in state money over the past eight months, inspectors found pools of raw sewage in two rooms. The inn has been such a frequent destination for the town's first responders that, in fall 2022, Sachdev agreed to pay the municipality $22,500 a month, plus a one-time sum of $75,000, to defray the cost of emergency services.

In Berlin, town officials struggled for years to get Sachdev to address their concerns about persistent crime and drug use at the Hilltop Inn, one of Sachdev's highest-grossing properties. After Berlin Police Chief James Pontbriand successfully petitioned DCF late last year to limit the number of rooms the motel could rent to people in the state housing program, Sachdev and his associate, Uday Dholakia, agreed to regular meetings with Pontbriand and Berlin officials, with the goal of reaching an accord that would allow the Hilltop to operate at full capacity.

Earlier this month, after a dramatic decline in 911 calls involving guests at the hotel, the Berlin Selectboard agreed to let Sachdev fill all 80 rooms, up from around 60. During a recent meeting of town officials, Hilltop management, DCF and social service workers, Dholakia attributed this sudden turnaround, in part, to "a beautiful camera right in the front parking lot."

"Once people are here, we want them to stay here for as long as they're able to," Dholakia said at the meeting. "We provide so many things that other hotels don't. You are very fortunate to come here." In exchange for lifting the room cap, Sachdev will pay the town $400 a month, plus $70.75 an hour for every police officer and ambulance worker who responds to the motel.

Pontbriand said he takes no pleasure in accepting money from a private business owner, though he thinks there has been some improvement in Sachdev's willingness to cooperate with the town. At the end of last month, the Hilltop took in several guests who "no sooner hit the ground here and started stealing cars and stealing stuff from Walmart," according to Pontbriand. "We had a conversation with them, like, 'Hopefully, these people aren't going to stick around long,' and they removed them from the hotel within 24 hours. And that's not been my experience dealing with them in the past." But in Pontbriand's view, Sachdev's sudden responsiveness is the result of wanting to increase his monthly billings.

"There's a real financial incentive for them," Pontbriand said. "And there's very little money being put back into that hotel. No one would pay to stay there." The Hilltop's overall condition, in his estimation, is "deplorable."

Just last month, Pontbriand had to confront Sachdev about another issue: The Hilltop management was evicting people and telling them that if they didn't get off the premises, the police chief would shut down the hotel and force everyone out onto the street. Pontbriand — who doesn't have the power to do that — said that kind of fearmongering erodes trust between the town and motel residents, who often need help from first responders for mental health crises, overdoses and other emergencies.

click to enlarge

- Zachary P. Stephens

- Cars filled with personal items and open shipping containers in the parking lot of the Quality Inn

"That's been my chief heartache since the inception of this program — you're placing people here with a lot of needs, and you didn't put any kind of support structure in place, which is a real burden for the municipality," the chief said. At a meeting with town officials in February, Sachdev apologized to Pontbriand for throwing him under the bus and assured him that it wouldn't happen again.

At the Brattleboro Quality Inn, Sachdev would instruct his staff to tell residents that their rooms had been treated for bedbugs when they hadn't, said Bobbie Trujillo, who lived and worked there as a housekeeper and manager between December 2020 and June 2022. "They would rent rooms out where they knew that the plumbing didn't work or something else was wrong," Trujillo said. "They would just tell us to clean it up and get them in there, because they need that money! They need those vouchers! They need those vouchers! Gotta keep those vouchers up!" When someone left the hotel before the end of the month, Trujillo said, Sachdev simply wouldn't report it to DCF so he could continue to collect money for the room; at the same time, he'd rent it out to someone else.

Both Trujillo and Ouellette acknowledged that some guests do trash their rooms. But Trujillo feels that the owners use that as an excuse not to put money back into the property, and then they blame tenants for problems caused by their lack of maintenance. When she lived there, Trujillo said, the top floor flooded every time it rained because of a leak in the roof. "There are so many rooms in there that have mold that's just not gonna go away, no matter how many times you spray it with bleach," she said.

While Ouellette was living at the Quality Inn, at least nine people died in their rooms, mostly from drug overdoses, according to records from the Brattleboro Police Department. In one case, someone had been dead at least four days before her body was discovered, the medical examiner's report noted. Rather than hire a professional hazmat crew, Ouellette said, the hotel management would instruct its own staff — most of whom, like Ouellette, were residents themselves — to clean the rooms where the bodies had been found, so they could be turned over as quickly as possible to the next guest. "They treated us as subhuman," Ouellette said. Trujillo shared that assessment. When she quit her job at the Quality Inn in June, six months after moving into her own apartment, she started going to therapy. "I was pretty traumatized by the stuff I'd seen," she said.

Michael Hutchins, another former Quality Inn resident, has been in the dark about his security deposit since he left the hotel in December. All of his attempts to reach Sachdev have been unfruitful. "He's a ghost," he said. Mostly, Hutchins is frustrated by the indignity of having to chase down money that the state, in theory, had promised him. His caseworker from Groundworks Collaborative, a local social service provider, got him the papers to file a small claims suit against Sachdev, but the courthouse is in Newfane, a 20-minute drive from Brattleboro. Hutchins doesn't have a car, and there's no public transportation that would get him there.

"I'd be willing to go without the money to know that that guy doesn't have it," Hutchins said, referring to Sachdev. "It's the principle of the thing. You shouldn't be able to make money, hand over fist, on people who can't do anything about it."

The original print version of this article was headlined "No Return | Motel owners are withholding security deposits meant to benefit homeless tenants"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Housing Crisis, homelessness, unhoused, motels, Brattleboro

More By This Author

About The Author

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Speaking of...

-

Brattleboro’s Hermit Thrush Brewery to Close

Apr 2, 2024 -

State to Open Temporary Homeless Shelter in Downtown Burlington

Mar 14, 2024 -

Decker Towers Tenant Charged With Pepper Spraying a Woman in Stairwell

Feb 29, 2024 -

Decker Towers Residents Plead for Help From the Burlington City Council

Feb 26, 2024 -

The Fight for Decker Towers: Drug Users and Homeless People Have Overrun a Low-Income High-Rise. Residents Are Gearing Up to Evict Them.

Feb 14, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 3. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 4. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 5. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 6. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 7. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News