click to enlarge

- sally pollak

- Left to right: Greg Soll, Christopher Miller and Aaron DellaCroce of Northern Spirulina

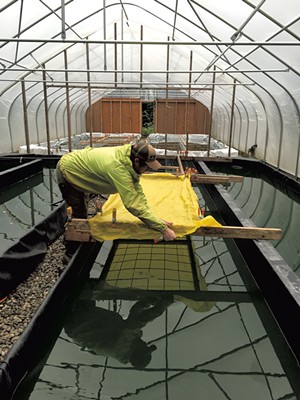

In a greenhouse near the end of a long dirt road in Johnson, three farmers are growing, harvesting and selling a one-of-a-kind crop in Vermont: spirulina. Hidden in the woods on an old goat pasture, Northern Spirulina raises the organism in four pools of water in a greenhouse. The shallow, wood-framed ponds are teeming with hundreds of billions of the specimen that some consider a superfood.

Spirulina, a type of blue-green algae, is high in protein (about 60 percent) and rich in nutrients including iron, beta-carotene, B vitamins and magnesium. NASA has conducted research on astronauts eating spirulina on space voyages. International aid organizations recognize its benefits in combating malnutrition. And the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, a division of the National Institutes of Health, is funding a study to investigate the anti-inflammatory properties and mechanism of spirulina.

Closer to home, at the Inn at Shelburne Farms, diners can eat spirulina in their pesto or butter. The latter turns an "awesome" shade of blue-green when the algae from Northern Spirulina is added to it, said chef de cuisine Weston Nicoll. He's folded spirulina into brioche dough and admires the look of the spirulina butter when it's spread on dark emmer bread.

"The fresh spirulina has a really delicate flavor, and we like the nutritional aspect," Nicoll said. "We have a lot of fun playing with it, I have to say."

click to enlarge

- sally pollak

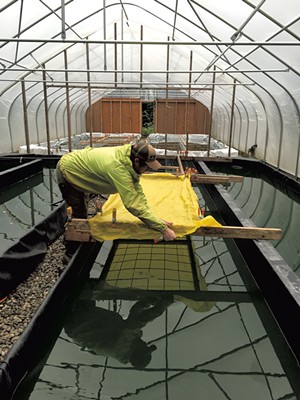

- Straining spirulina

Spirulina has been available for decades as a dietary supplement in powdered or capsule form. Kimberly Evans, a registered dietician at the University of Vermont Medical Center, said she recommends spirulina often for managing the risks of chronic diseases and for helping people meet their nutritional requirements.

"What I love about spirulina is that it is a very concentrated source of nutrition," Evans said. "The fact that somebody is adding that industry [in Vermont] is pretty cool."

Spirulina, a one-celled organism, is a cyanobacterium that gets its energy through photosynthesis. (It is not the kind of cyanobacteria typically called blue-green algae that produces toxic blooms in Lake Champlain and other bodies of water.)

Northern Spirulina is the only farm in Vermont — of some 7,300 agriculture operations — that cultivates spirulina. And it is believed to be the only operation in the Northeast that grows spirulina for human consumption. (A Rhode Island producer raises it for fish food.)

The founder of the employee-owned farm, Christopher Miller, 28, grew up in western Massachusetts and moved to Burlington to attend the University of Vermont. Then an environmental studies major, Miller discovered spirulina during his sophomore year in college when he spent a semester on a commune in southern India.

His plan was to work on a reforestation project, but Miller's interest shifted when he learned about spirulina. His teachers were from the Antenna Foundation, a Geneva-based organization whose projects include local and sustainable production of spirulina in developing nations. When members of Antenna arrived at the commune to teach about and build spirulina pools, Miller was hooked.

"I learned how to grow it eight years ago, and I've been obsessed with it," he said, standing in his greenhouse on a rainy September day. He gestured toward the two friends — Greg Soll and Aaron DellaCroce — he recruited for his endeavor and said, "Now these guys are obsessed with it, too." Miller's girlfriend, Jonna Jermyn, is also a partner in the business. He juggles the spirulina farm with his "day job" with Avaaz, a U.S.-based organization that assists people worldwide with social action and environmental initiatives.

In India, Miller wrote an English-language manual about how to grow spirulina. The method used at the rural commune was rudimentary and inexpensive, with the pool costing less than $100 to build. In a medium that consisted mostly of water, urine was used as fertilizer and mixed with iron, ash and vinegar.

click to enlarge

- sally pollak

- Aaron DellaCroce holding spirulina

"If you have other things available, it tastes a little better," Miller said. "But the fact that you could literally survive off these things that you could more or less scrounge was incredible to me."

At parties, commune members painted themselves with the algae — for fun and skin health. They ate the spirulina raw.

"We'd strain it out of the pool, wash it, put salt and lemon on it," Miller said. "It was a vegan commune, and we'd incorporate it into vegan dishes."

When he returned to Burlington, Miller began experimenting with growing spirulina in aquariums. As he played around with spirulina, Miller harbored a dream of doing more with it, he said. "Once I realized the market and [that] you could only get the dry stuff that was just lifeless, I was dreaming," he said. "It would be so great to have our own pools."

Two years ago on the land in Johnson, Miller started to grow spirulina in outdoor pools. Then, last year, he, Soll and DellaCroce built a greenhouse with double-insulated plastic and four pools, each about one foot deep.

click to enlarge

- sally pollak

- Straining spirulina with squeegee.

The pools hold a medium that fosters growth and mimics the lake environment in a warm locale where spirulina would naturally live, Miller explained. It consists primarily of local spring water, with added iron, sea salt, Epsom salts, green tea and naturally forming nitrogen for fertilizer. A pump agitates the pool water to get light and air into the mixture, which aids in the bacteria's growth. The ideal water temperature for spirulina growth is 98 degrees, Miller said.

"In perfect conditions, spirulina will double in a day," he noted.

DellaCroce does most of the harvesting, a job he usually undertakes three days a week. The spirulina in its medium is pumped into a wooden frame that DellaCroce sets above the pool. The frame holds a fine-mesh fabric that strains the algae; the excess water drains back into the pool. Then DellaCroce uses a small, squeegee-like instrument to gather and further strain the substance, before squeezing the crop with his hands. He's left with a big ball of green glop. This live spirulina is then dumped into a five-gallon bucket. One pound of spirulina contains roughly 25 billion individual spirulina specimens.

DellaCroce likes to skim off the harvest and eat the spirulina raw. He and his partners also mix it into juice, smoothies and salad dressing.

"As of now, I'm avoiding all doctors and I feel great," said DellaCroce, 28. "Physically, I'm not like I was when I played soccer in high school. But I think clearer than a lot of people out there."

click to enlarge

- sally pollak

- Frozen spirulina cube in apple cider

He notices an "energy boost" after eating a lot of spirulina, too, DellaCroce said. But he acknowledged that a healthy young man might not be the prime spirulina consumer.

"Most of the people we grow it for have no idea they need it," he said. "Or what it is."

The bulk of the spirulina cultivated in Johnson is put on ice and trucked to Williston, where the farm partners freeze and package it in a certified kitchen, according to Miller. The product is available raw and frozen via the company website, and it's sold in bags of individually wrapped frozen cubes at area stores, including Pete's Greens in Waterbury and Healthy Living Market & Café in South Burlington.

"It's local, it's extremely healthy, and it's in a new form other than powder and pills," said Eli Lesser-Goldsmith, co-owner of Healthy Living. "New local brands and products like this that are trending can always be attractive to our guests."

A frozen spirulina cube can be dropped in a drink or thawed for about a minute and rubbed onto your face. "It applies like lipstick," Miller said. "You've got yourself an algae mask that costs a dollar."

The Northern Spirulina producers will be at the Burlington Farmers Market most Saturdays through the end of the season and hope to have a spot at the winter market, Miller said.

Because spirulina favors warm conditions for its growth, it's a seasonal crop in Vermont. The greenhouse cultivation likely will come to an end next month, when the farmers will "retire" their pools. They'll save five gallons of spirulina in an indoor aquarium over the winter and start growing the crop again next spring.