Published March 1, 2013 at 4:00 a.m. | Updated April 27, 2017 at 12:49 a.m.

How many species of living things exist in Vermont? Ecologists estimate between 26,000 and 45,000, and that's not counting invisible-to-the-naked-eye bacteria and viruses. But no one really knows for sure how many plants and animals share the state with us humans. The Vermont Atlas of Life project aims to find out. And you can help: During your next walk in the woods, or bird watching in your own backyard, you could contribute to an invaluable research database that will be used to serve the well-being of the state and its environment for years to come.

Earlier this year, the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE), located in Norwich, launched the Vermont Atlas of Life project to foster a greater understanding of every existing species in the state. Plants, fungi, insects, arachnids, mollusks, reptiles, amphibians, fish, mammals, birds and even protozoa are all being carefully photographed by Vermont's residents and visitors. Anyone can participate by submitting photos or adding their two cents on the identity of a species submitted by someone else.

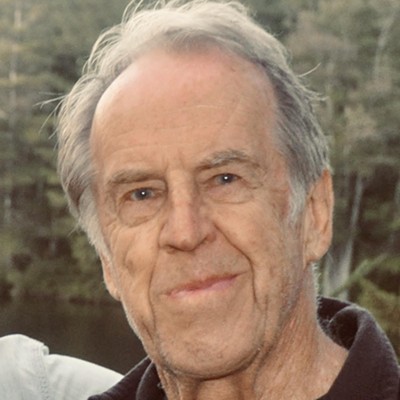

Crowdsourcing such information, says Kent McFarland — the project's creator and a conservation biologist at the VCE — is possible today thanks to the technology of smartphones and apps like iNaturalist. This app allows you to upload a photo of an interesting species you spot while walking your dog, taking a hike or digging in your garden. Then you can attempt to identify it yourself or rely on the help of other participants in the project to determine what you've seen.

While iNaturalist includes similar projects taking place all over the world, Vermont and Ohio are the only two states so far that have set out to document every living species within their borders. One of iNaturalist's most passionate participants in Vermont, Montpelier-based ecologist Charlie Hohn, has contributed more than 2500 photographs, many of which he posted long before McFarland launched the Vermont Atlas project.

"We have some amount of info about rare plants or species that are ecologically useful," Hohn explains, "but for many species, even common or invasive ones, we know very little about their range across the state.

"We know even less about the past," Hohn continues. "Did you know some habitats and natural communities in California were literally destroyed before people had time to figure out what they were? By adding information to iNaturalist and the Vermont Atlas of Life project, I am adding to a global pool of knowledge that could be helpful in the future."

This type of research isn't new to McFarland. His Vermont eBird project has documented more than two million birds in the state over the past two years, and continues to thrive.

"The West Nile virus is a good example of what this kind of crowdsourcing research can do," McFarland says. "When the virus was first introduced in the U.S., it was killing a lot of crows and chickadees; the eBird project was used on a national scale to help see where the biggest drops in species were taking place."

While it's important to observe potentially threatened species, the discovery of a new one is even more exciting, and a realistic goal, according to McFarland. Other conclusions that might emerge from the developing data include the growth rate of a certain type of tree or flower and a better understanding of the spread or specific locations of a particular species in the state. The potential uses for information submitted to the Vermont Atlas of Life are almost endless.

When participants submit their observations through iNaturalist, "there's a lot of interesting conversation that takes place," McFarland says. For example, short-tail and long-tail weasels are almost identical, but discussions among observers have helped identify significant differences between the two breeds.

"Someone entered a photo of a dragonfly they hit with their car," McFarland notes, offering another example. "One of the dragonfly experts in the state saw the posting on iNaturalist and identified it as a species of dragonfly that's actually very rare. With the location automatically tagged on the photo through the program, they were also able to discover a new breeding site."

While anyone can participate, a photograph is essential if you want your observation to be identified by another participant. As soon as someone else concurs with your identification, the data qualify as "research grade" — that is, more reputable.

"If people disagree with your identification, then you can discuss it or realize it is wrong and change it," says Hohn. "If I don't know what something is, but I've taken a good photo, someone else may be able to identify it for me." This project, Hohn says, has turned his routine hikes into "treasure hunts."

As the Vermont Atlas of Life takes off, McFarland is developing an encyclopedia of every living thing with proper names, in the form of a "taxonomic tree of life." Whether or not you contribute observations yourself, you can visit the real-time, constantly evolving website to follow discoveries as they are posted.

"We have the opportunity to log everything in nature and what it looks like now, on a massive scale," McFarland says. "It's an unprecedented baseline of a place we all love now."

The Vermont Center for Ecostudies, Norwich, 802-649-1431.

Le projet Vermont Atlas of Life vise à consigner toutes les espèces vivantes

Combien d'espèces vivantes recense-t-on au Vermont? Selon les écologistes, il en existerait entre 26 000 et 45 000, sans compter les bactéries et les virus invisibles à l'œil nu. En réalité, personne ne sait véritablement avec combien de plantes et d'animaux nous, êtres humains, partageons notre État. Le projet Vermont Atlas of Life se propose de répondre à cette question. Vous pouvez d'ailleurs y contribuer : lors de votre prochaine balade en forêt ou quand vous observerez les oiseaux derrière chez vous, vous pourriez enrichir une base de données de recherche inestimable qui servira à améliorer le bien-être et l'environnement au Vermont dans les années à venir.

Plus tôt cette année, le Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE), situé à Norwich, a lancé le projet Vermont Atlas of Life pour promouvoir une meilleure compréhension de toutes les espèces présentes dans l'État du Vermont. Plantes, champignons, insectes, arachnides, mollusques, reptiles, amphibiens, poissons, mammifères, oiseaux et même protozoaires sont soigneusement photographiés par les résidents et les visiteurs du Vermont. Tout le monde peut participer en soumettant des photos ou en aidant à identifier une espèce soumise par quelqu'un d'autre.

« Il est possible d'avoir recours à l'externalisation ouverte pour recueillir de telles informations, dit Kent McFarland, créateur du projet et biologiste de conservation au VCE, grâce à la technologie des téléphones intelligents et à des applications comme iNaturalist. Cette app vous permet de télécharger en amont une photo d'une espèce intéressante repérée pendant que vous promenez votre chien, que vous faites une randonnée ou que vous bêchez votre jardin. Vous pouvez ensuite tenter de l'identifier vous-même ou vous en remettre à d'autres participants pour déterminer ce que vous avez vu.

Si iNaturalist comprend des projets semblables partout dans le monde, le Vermont et l'Ohio sont les deux seuls États à avoir entrepris de recenser toutes les espèces vivantes à l'intérieur de leurs frontières. L'un des participants les plus passionnés du projet iNaturalist au Vermont est l'écologiste de Montpelier Charlie Hohn, qui a transmis plus de 2 500 photos, dont beaucoup avaient été publiées bien avant le lancement par Kent McFarland du projet Vermont Atlas.

« Nous avons une certaine quantité d'informations sur des plantes ou des espèces rares qui sont utiles sur le plan écologique, explique Charlie Hohn, mais pour beaucoup, même des espèces communes ou envahissantes, nous savons très peu de choses sur l'aire de répartition à l'échelle de l'État.

« Nous en savons encore moins sur le passé, poursuit M. Hohn. Saviez-vous que certains habitats et communautés naturelles en Californie ont été littéralement détruits avant qu'on ait même eu le temps de les identifier? En ajoutant de l'information à iNaturalist et au projet Vermont Atlas of Life, j'alimente un bassin de connaissances susceptible d'être utile dans le futur. »

Ce type de recherche n'est pas nouveau pour Kent McFarland. Son projet Vermont eBird a permis de recenser plus de deux millions d'oiseaux dans l'État au cours des deux dernières années, et il est encore en pleine activité.

« Le virus du Nil occidental est un bon exemple de ce qu'une recherche par externalisation ouverte comme celle-ci peut produire comme résultat, dit-il. Lorsque ce virus a été introduit aux États-Unis, il a causé la mort d'un grand nombre de corneilles noires et de mésanges; le projet eBird a permis de déterminer, à l'échelle nationale, où survenaient les déclins les plus prononcés de ces espèces. »

Selon lui, s'il est important d'observer les espèces menacées de disparition, la découverte d'une nouvelle espèce – objectif réaliste – présente encore plus d'intérêt. Les données recueillies pourront donner lieu à d'autres conclusions, notamment sur le taux de croissance d'un certain type d'arbre ou de fleur, et à une meilleure compréhension de la dissémination ou des emplacements précis d'une espèce particulière dans l'État. Les usages possibles des informations soumises au projet Vermont Atlas of Life sont pratiquement infinis.

M. McFarland raconte que les observations des participants qui collaborent à l'aide de iNaturalist donnent lieu à des conversations très intéressantes. « Les hermines et les belettes à longue queue, par exemple, sont presque identiques, mais les échanges entre observateurs ont permis de repérer des différences considérables entre les deux espèces.

« Quelqu'un a transmis une photo d'une libellule qu'il avait frappée avec sa voiture, poursuit-il. L'un des experts de l'État a vu la photo sur iNaturalist et l'a identifiée comme étant une espèce de libellule très rare. Comme l'emplacement est automatiquement indiqué sur la photo par le programme, il a aussi été possible de découvrir une nouvelle aire de reproduction. »

Tout le monde peut participer, mais il est essentiel d'avoir une photo si on veut que l'espèce observée puisse être identifiée par un autre participant. Dès qu'une autre personne est d'accord avec votre identification, l'information est considérée « de qualité recherche », donc plus fiable.

« Si quelqu'un conteste votre identification, dit M. Hohn, alors vous pouvez en discuter ou bien constater que vous aviez tort et changer le nom. Si je ne connais pas une espèce, mais que j'ai une bonne photo, il se peut qu'une autre personne ait la réponse. »

Pour lui, ce projet a transformé ses randonnées habituelles en « chasses au trésor ».

Avec le projet Vermont Atlas of Life, Kent McFarland élabore une encyclopédie d'êtres vivants, avec les noms justes, sous la forme d'un « arbre de vie taxonomique ». Que vous y contribuiez personnellement ou non, vous pouvez tout de même visiter le site Web en temps réel et suivre les découvertes à mesure qu'elles sont publiées

« Nous avons l'occasion, dit M. McFarland, d'alimenter ensemble un répertoire de tout ce qui existe dans la nature – photos à l'appui. Il s'agit d'une documentation de référence sans précédent sur un lieu que nous aimons tous.

The Vermont Center for Ecostudies, Norwich, 802-649-1431.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Counting Crows... And Everything Else"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Regulators Are Poised to Let Vermont Gas Buy Methane From a Distant Landfill

Oct 21, 2022 -

Video: Talking Trees With Burlington Arborists

May 5, 2022 -

Signs of Fall: Using Free Apps and Phenology to Track the Rhythms of the Year

Aug 24, 2021 -

Increasing Downpours Impede Efforts to Improve Lake Champlain's Water Quality

Aug 18, 2021 -

Vermont Senate Blocks Governor's Act 250 Reform Order

Feb 4, 2021 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

![Spring Amphibian Migration [SIV487]](https://media2.sevendaysvt.com/sevendaysvt/imager/u/square/5357306/episode487.jpg)