Published October 17, 2007 at 9:31 p.m.

When Jason Gerrard started eighth grade at Edmunds Middle School in Burlington, his formal sex education to that point might have been acquired somewhere between the pharmacy and the produce section of his local supermarket.

“It was just your typical demonstration of how to put a condom on a banana. That’s about it,” Gerrard recalls. “All the kids laughed and asked silly questions. It was nothing special.”

Apparently, Gerrard’s mother wasn’t much more informative on the subject. “She never wanted to talk to me about sex ed, as I found out not too long ago,” adds the now 17-year-old, a freshman at the University of Vermont. “She said, ‘Jason, there are only three words I have to say to you about your sex life: Use a condom.’”

Like millions of other American teens, Gerrard could have gone through his entire secondary education learning nothing about human sexuality beyond some basic anatomy and a few tips for avoiding sexually transmitted diseases. (In many schools across the U.S., even some in Vermont, the official “facts of life” begin and end with the abstinence-until-marriage mantra of “Just say no.”) But then Gerrard’s mother enrolled him in a yearlong, comprehensive sex education class called “Our Whole Lives.”

For 28 hour-and-a-half-long sessions, Gerrard received frank, no-nonsense lessons in human sexuality that would make some adults blush. The discussions, films, role-playing exercises and, yes, even overnight sleepovers covered such sensitive and usually taboo topics as abortion, masturbation, sexual fantasies, incest, rape and gender-reassignment surgery.

“Our Whole Lives” (OWL) isn’t offered by any Vermont school district, nor will you find it at the state health department, the Red Cross or Planned Parenthood. It’s taught every Sunday morning at the First Unitarian Universalist Society of Burlington. And Sunday school has never been so stimulating.

The OWL curriculum was developed nationally by the Unitarian Universalist Association in conjunction with the United Church of Christ. More than a decade and $1 million went into creating the program, which was designed to combat the physical and psychological harm that premature sexual activity can cause, from low self-esteem to STDs to unwanted teen pregnancies. Recognizing that the abstinence-only message leaves young people with too many unanswered questions, OWL provides them with the most powerful tool at their disposal: age-appropriate and fact-based information.

Amelia Schlossberg is a 16-year-old junior at Burlington High School who went through OWL at the UU three years ago. She remembers being nervous, confused and more than a little embarrassed about taking sex ed at her church. “There was a lot of laughing and giggling the first day of class. You’re sitting there telling kids, ‘Oh, my gosh! My parents are forcing me to come to this. I can’t believe I’m here!’” she says. “But of course I was curious. I mean, who isn’t at that age?”

One of their first assignments, Schlossberg recalls, was to build a three-dimensional model of human reproductive organs using nothing more than pipe cleaners, cotton balls, toilet paper rolls and tape. At first, she says, the students were too shy to use the proper anatomical names for male and female sex organs. Soon, however, these seventh- and eighth-graders could not just name the body parts but describe their functions.

Later that year, the students watched a slide show depicting people making love. Using realistic drawings, the slides demonstrate in graphic detail how people get it on, whether they’re thin or fat, tall or short, young or old.

But as Gerrard points out, “OWL teaches you a lot of life skills that don’t necessarily have to do with physically how you go about your business.” In one role-playing exercise, for instance, the teens picked names of their fellow students out of a hat and then practiced asking each other out on dates. The exercise teaches kids how to accept romantic advances, and how to politely decline them.

For Schlossberg, what’s particularly memorable about the lesson is that it didn’t assume people only make overtures to the opposite sex. One of the fundamental principles of OWL is that, in keeping with the Unitarian value of respecting diversity, issues such as bisexuality, homosexuality and gender identity are incorporated into the curriculum as normal aspects of human sexuality. “The course really helped me understand all the different kinds of sexual orientation and how deep and spiritual sexuality can be for people,” Gerrard says.

Reverend Gary Kowalski is the minister of the First Unitarian Universalist Society of Burlington and was instrumental in bringing OWL to Vermont. These days, Kowalski says he’s become “evangelical” about promoting comprehensive sex education. OWL, which has been taught at the UU church since 1996 — the Burlington congregation was the first in the country to “field test” the curriculum before its national release — is offered free of charge, to congregants and non-congregants alike, as space allows.

“I think that our culture is very conflicted about sex,” Kowalski says. “Most of the values education that young people receive is from the broader culture, where they get these terribly, terribly mixed messages.”

In today’s conservative climate, one can find those “mixed messages” emanating from some high offices. In December 2004, Governor Jim Douglas had a historically significant lamp removed from his desk in Montpelier because it depicted a naked woman. The lamp, a replica of the 19th-century statue by Hiram Powers entitled “The Greek Slave,” was an iconic image of the abolitionist movement. But as Jason Gibbs, Douglas’ press spokesman, told the Associated Press at the time, “It may, frankly, be awkward to explain why there is a nude Greek slave on the governor’s desk to a third-grader.”

For his part, Kowalski saw that incident as a missed opportunity. “I suppose you might tell an 8-year-old that nudes have been painted and sculpted by artists for hundreds of years because the anatomy of the human form is considered one of the most beautiful creations of nature,” Kowalski told his congregation in May 2005. “You could tell a child that your body is your most precious possession, and that this sculpture was made to teach us that no one’s body should ever be sold or degraded or abused by another person.

“But with so many teachable moments,” Kowalski continued, “I’m afraid the governor’s office may have inadvertently sent out a bad lesson for any child old enough to watch the evening news — that breasts are dirty and bodies are nasty . . .”

While the story has a 1950s quaintness, Kowalski says it reflects a cultural psyche that’s both obsessed with and deeply repressed about its own sexuality. Fundamentally, there’s no difference between Attorney General John Ashcroft’s spending $8000 on drapes to cover the exposed breast of the “Spirit of Justice” statue in Washington, D.C., and the flight attendant at Burlington International Airport who kicked a woman off a plane last December for refusing to cover herself while nursing her baby. Such incidents, Kowalski says, reveal a collective dysfunctional attitude toward something as commonplace as the human body.

******************

It’s no coincidence that OWL was launched in 1996, the same year that President Bill Clinton signed into law a welfare-reform bill that included an “abstinence-only” provision. Since then, the federal and state governments have spent more than $1.5 billion on abstinence-only-until-marriage programs, including $176 million last year alone. Many of these programs teach scientifically flawed, if not outright false, information.

In December 2004, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) published a report entitled “The Content of Federally Funded Abstinence-Only Educational Programs.” In it, he revealed that two-thirds of the curricula used by federally funded abstinence-only programs contained serious medical inaccuracies, including claims such as these: Pregnancy occurs once every seven times a hetero couple has sex with a condom; sweat and tears can transmit HIV; one in every 10 women who has an abortion becomes sterile; and marriages are more likely to fail when the spouses have had premarital sex.

Ironically, while federal abstinence-only spending has ballooned in the last six years, a 2006 University of Pennsylvania study revealed that most Americans, regardless of their political view or religious affiliation, say they favor medically accurate and age-appropriate education. That education would include information on both contraception and abstinence, according to the study.

The Bush administration’s emphasis on abstinence-only programs has had some disastrous consequences, such as higher rates of STDs, teen pregnancies and teen births. An eight-year study by researchers at Yale and Columbia Universities found that 88 percent of sexually active teens who took an “abstinence pledge” — a central theme in many faith-based curricula — eventually had intercourse before marriage. Moreover, those pledgers who became sexually active were less likely to use condoms and more likely to experiment with riskier activities such as oral and anal sex than those who didn’t make the pledge. They were just as likely to contract an STD.

On the basis of such evidence, in recent years about a half-dozen states have opted out of federal Title V, or abstinence-only, funding. Vermont is not among them. Last year, Vermont accepted about $66,000 in Title V funds, which required a state match of about $49,000. According to Commissioner Sharon Moffatt at the Vermont Department of Health, that money was spent primarily on media campaigns — TV and radio ads, posters and pamphlets — educating parents of young teens about the links between drug and alcohol use and unintended sexual activity. Though Congress put the brakes on abstinence-only funding last spring, on September 27 it reauthorized Title V funding for another three months.

Vermont law does require that students receive a “comprehensive health education” that includes instruction on HIV, other STDs and responsible decision-making surrounding sexual activity. Kate Cassi O’Neill, the HIV prevention coordinator at the Vermont Department of Education (DOE), explains that the state also provides all school districts with “health education guidelines” to help them create their own course curricula.

That said, the DOE does not mandate or endorse a specific sex-education program, nor does it review, monitor or approve of the material students are taught. According to O’Neill, more than half of Vermont’s school districts and supervisory unions teach a locally developed health curriculum — meaning, the material out there can vary widely.

******************

Not surprisingly, local parochial schools have adopted a faith-based approach to teaching human sexuality. For instance, the sex education curriculum at the St. Joseph School in Burlington, which begins in fifth grade, is taught as part of religious instruction and is based on the tenets of the Catholic Church. “We do have an obligation to follow the state’s policies regarding bullying and harassment,” notes Principal Evelyn Rogerson. But when it comes to sexuality, she says, “We talk a little bit about the STDs and that kind of thing, but not a whole lot.”

Similarly, students at Rice Memorial High School in South Burlington are taught the basic biology of human sexuality, and the program places a “strong emphasis” on abstinence until marriage, according to Rice’s principal, Father Bernard Bourgeois. Subjects such as birth control and masturbation are not included in the curriculum, he adds, and any mention of abortion or homosexuality will “follow Catholic teachings to the letter.” That is, they’re both deemed morally wrong.

While public schools in the state take a more comprehensive approach to adolescent sex ed, often they’re limited, too — not by religious dictates, but by the difficulty of cramming a lot of information into a small span of classroom time.

Mike Brown is a health teacher at BFA-Fairfax. He says that in the past three to five years, the school’s health curriculum has “grown by leaps and bounds.” While he believes the community has been “very supportive,” Brown acknowledges that he has only nine weeks to cover a long list of adolescent health issues, ranging from human sexuality to teen suicide, drug and alcohol abuse, eating disorders and negative body images.

Some public schools, like their parochial counterparts, offer less-than-thorough coverage of the birds and the bees. When Amelia Schlossberg was a sophomore at Burlington High School, an instructor with an abstinence-only approach came to speak to her class. The program, called “W8ng: Because UR Worth It,” is taught by Robin Ng of Hanover, N.H.

“She came in and did this two-day presentation that was three hours long, with PowerPoints and all these flashy images,” Schlossberg recalls. “She compared having an abortion to this guy who got his arm stuck under a rock out West and had to saw it off with a dull blade. To me, that was a really bizarre comparison.”

Schlossberg, who had already completed the UU’s OWL program by then, admits she found some of the woman’s presentation convincing. “Basically, her overall message is that if you have a lot of sex, it makes you bond less with your partner,” Schlossberg says. “And if you have a lot of sex before marriage, you’re more likely to get a divorce.”

Seven Days contacted Ng, who confirmed that her lesson compares getting an abortion to sawing one’s arm off in the wilderness, since both can seem like desperate decisions with no other options.

“I try to get [students] to understand that a lot of people who say, ‘I would never have an abortion’ — when they find themselves caught in that situation, they feel trapped, just like that guy out West,” Ng explains. “And they may make a decision that they wouldn’t have thought they’d ever do, because they don’t see any other way out.”

She adds, “I want students to understand that even if they’re pro-life, there’s more than just the baby who is the victim.”

Ng says she also tells students that too much premarital sex can make subsequent relationships falter. That claim, she says, is based on research about oxytocin, a hormone released in the body during an orgasm that purportedly causes couples to bond.

Ng’s assertion may be based on statements made by Dr. Eric James Keroack, a Massachusetts gynecologist whom Bush appointed deputy assistant secretary for Health and Human Services. According to a November 17, 2006, story in The Boston Globe, “Keroack said teenage sexual activity blunts the brain’s ability to develop emotional relationships.” However, the Globe article also points out that scientists conducting research on oxytocin in rodents describe Keroack’s theory as “an extreme reading of the data.”

Finally, Ng was asked what sort of information she imparts to her students about birth control methods. Ng says she tells students that, when it comes to preventing gonorrhea and chlamydia, condoms have a 50 percent failure rate “under real-life conditions.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list the failure rate of male condoms at 2 percent and consider them “highly effective” in preventing the spread of HIV and other STDs — when people know how to use them properly.

******************

Contrary to many of the scare tactics used by abstinence-only proponents, OWL takes a more “sex-positive” approach to educating teens. According to the OWL “bill of rights,” teens may ask any questions they like about sexuality and discuss any sexual issues that interest them. They can expect to receive full and accurate information and be treated with respect by their instructors.

Kecia Gaboriault has been an OWL instructor at the UU Society in Burlington for several years. Gaboriault, who spent 10 years working with kids as a social worker in Chittenden County, says one of the guiding principles of OWL is to create a safe space where teens can explore their own attitudes toward sexuality and interpersonal relationships.

“You may have a kid seated in the classroom who doesn’t even know he’s gay yet. This environment provides him with safety,” she says. “Whereas in a public school, once you out yourself, who knows?” In fact, to protect students’ privacy, the OWL classroom at the UU church remains locked all year long; only students and instructors may enter.

That said, OWL does not preach a non-judgmental, “anything-goes” attitude toward sexuality, says Diane Freiheit, a Burlington sex therapist and OWL instructor. As she points out, the OWL philosophy recognizes that sex can be used to coerce, control, degrade and exploit people. As a result, the curriculum addresses not just physical safety, such as protecting oneself against rape and sexual assault, but also emotional safety, including maintaining positive body images and understanding the power differentials that can exist in relationships. Simply put, Freiheit says, the emphasis is always on expressing one’s sexuality in healthy and life-affirming ways.

But not too early. While it bears scant resemblance to an abstinence-only program, the OWL curriculum for seventh- and eighth-graders remains abstinence-based, in that it strongly discourages teens from having sex prematurely. Moreover, the instructors all say their goal isn’t to usurp the role of parents as primary educators of their kids. Parents of potential OWL students must sit through a two-hour orientation so they know exactly what kind of material their kids will be taught.

“We’re not pushing our morals, we’re not pushing our faith, and we’re not pushing our beliefs,” Gaboriault insists. “We’re there to give them truthful, accurate, trustworthy and real information from adults who care and are willing to work with them in their learning process.”

When anyone questions the efficacy of OWL, Kowalski points to recent data showing that the program’s graduates are more likely than their peers to delay the onset of sexual activity. For his part, Jason Gerrard at UVM says that OWL changed his attitudes for the better.

“One of the personal choices I made was not to engage in anything close to casual sex,” he says. “I now see sex as a spiritual thing and not just a physical thing.”

Eventually, Kowalski hopes to expand the OWL program at the UU beyond the one course currently offered for middle-schoolers. Elsewhere in the country, Our Whole Lives lives up to its name with curricula that begin when children are in kindergarten; others are designed for adults well into their senior years.

And Schlossberg, who just began her junior year at BHS, has moved on from OWL graduate to political advocate. Two weeks ago, she and Leah Marvin-Riley, a fellow OWL grad and student at Essex High School, spent five days in Washington, D.C., lobbying Congress to drop abstinence-only funding in favor of more comprehensive sex education. Not bad for a young woman who, just three years ago, was too embarrassed to say the word “vagina” in front of her peers.

Is there a spiritual component to OWL? Kowalski believes so. “I think love is spiritual. I think feeling at home in your own body is spiritual,” he says. “And I think being able to be intimate with another person, not just physically but emotionally, is spiritual.”

More By This Author

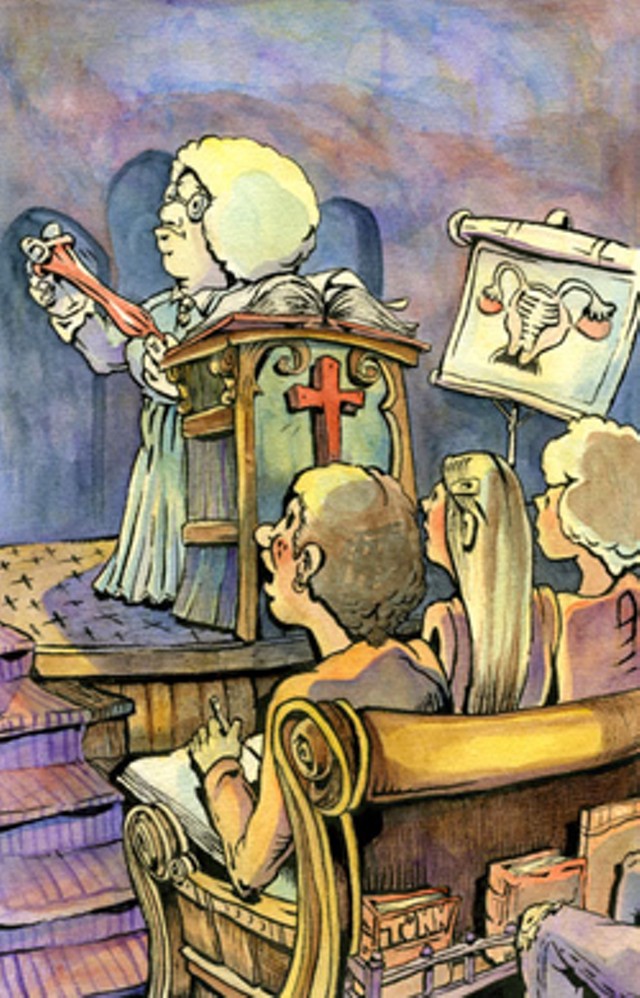

About the Artist

Michael Tonn

Bio:

Michael Tonn is still just eating gummy bears outside the Shopping Bag in Burlington. To see more of his work and to get in touch, go to michaeltonn.com or @dead_moons on Instagram.

Michael Tonn is still just eating gummy bears outside the Shopping Bag in Burlington. To see more of his work and to get in touch, go to michaeltonn.com or @dead_moons on Instagram.

Speaking of...

-

Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote

Apr 24, 2024 -

Senate Education Committee Advances Literacy Bill

Mar 15, 2024 -

Time to Vote! It's Town Meeting Day 2024

Mar 5, 2024 -

Teachers' Union Raises 'Significant Concerns' About Dyslexia Screening Bill

Feb 2, 2024 -

Q&A: Merrymac Farm Sanctuary in Charlotte Provides a Forever Home for Neglected Animals

Dec 6, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.