Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

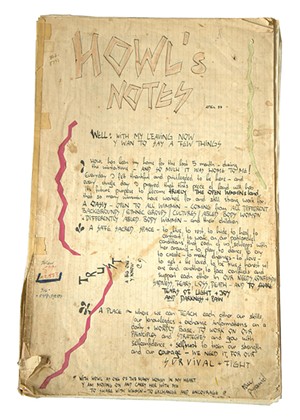

HOWLing at the Moon: A Women's Collective Grapples With a Gender-Fluid Future

Published November 20, 2019 at 10:00 a.m.

click to enlarge

- Karen Pike

- Front, left to right: Anya Schwartz and Glo Daley; Middle: Susan Smith and Xandi McMahon; Back: Lani Ravin, Stephie Smith and Vicky Tamas

In the mid-1980s, two decades before social media began fattening us with its empty-calorie buffet of human connection, a small cohort of lesbians settled a 50-acre parcel of wooded farmland on the edge of Camel's Hump State Park in Vermont. Known as Huntington Open Women's Land, or simply HOWL, this community followed in the footsteps of the back-to-the-land movement, rejecting capitalism and the patriarchy in favor of a life of rugged simplicity.

In the '70s and '80s, "women's lands" like HOWL began cropping up all around the country, drawing thousands of feminist homesteaders who were either gay, fed up with men or both. More recently, the women's land movement has attracted a spate of media attention, purportedly for failing to translate its principles to a generation that no longer views gender as a fixed biological fact.

The headline of a 2016 Vice article asked, "Who's Killing the Women's Land Movement?" as if some perpetrator were on the loose. This August, a New York Times story about HOWL framed the issue with slightly more tact: "Why Doesn't Anyone Want to Live in This Perfect Place?" Earlier this month, Openly, an LGBTQ media outlet sponsored by the UK-based Thomson Reuters Foundation, featured HOWL in a story titled, a bit sensationally, "Evolve or Die: The Stark Choice Facing America's 'Women's Lands.'" The dateline of that story misidentified Huntington as "Hamilton," which somehow seems symptomatic of the way the internet has supplanted geographic specificity.

I went to HOWL for a weekend retreat in mid-October, determined to find my spirit animal. This turned out not to be the point of the workshop; the Facebook post announcing the event invited participants to "engage" with their "anima," which I misread as "animal." Instead, we were supposed to connect with our primordial selves through Jungian scholar Clarissa Pinkola Estés' 1992 tome Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype, a mainstay of the spiritual feminist self-help genre.

But I also went to HOWL for non-spirit-animal reasons. It seemed suspicious to me that a movement so aggressively anti-mainstream in its heyday has drawn such extensive media rubbernecking in its waning years. On some level, the eulogizing of women's lands feels indicative of a deep-seated cynicism about utopian projects in general, and about those that seek to empower women in particular.

The decline narrative also projects a disillusioned longing: Now that these so-called "perfect places" are vanishing, where can we go to escape? Today, the idea that you can change the world by disconnecting from it — that you can even disconnect at all — seems increasingly absurd. In a sense, that's why I had to go see HOWL for myself. As a young queer woman, I'm both deeply skeptical and stupidly hopeful that a perfect, or even just good, place can exist untethered from the crappiness of modern life.

I arrived at HOWL late on a Friday afternoon, equipped with every piece of outerwear in my closet. The two guest rooms were booked, which meant I'd be rolling the dice vis-à-vis hypothermia at one of the campsites on the property.

At the top of the driveway, which marks the end of a dirt road, a weathered-looking barn leans slightly cattywampus on its foundation. Across from the barn is an 1850 farmhouse, whose interior has the warm nubbiness of a well-loved stuffed animal. In the narrow galley kitchen, hung with bunches of dried herbs and cast-iron cookware (labeled "vegetarian" or "omnivore"), you can find separate coffee makers for regular and decaf, but no paring knife. The fridge is a wunderkammer of fermented things in jars; if you run the microwave and the toaster oven at the same time, you'll blow a fuse.

A decade ago, HOWL had as many as six residents at a time living in the farmhouse and the barn, back when the latter was still structurally sound. Today, the HOWL population is one and a half, making it less of a commune than a homeshare. Meg Mass, who works full time at Philo Ridge Farm in Charlotte, rents a room in the farmhouse in exchange for $350 a month and caretaking duties. The other groundskeeper, Robin Baldwin, who can sometimes be spotted traipsing around the premises with a scythe, lives in her Toyota Tacoma until the temperature dips below 20 degrees.

Mass, 47, has a contagious giggle and magenta hair. (Confusingly, one of the other workshop participants, a 41-year-old documentary filmmaker from Montréal named Magenta, had blue hair; such are the perplexities of hanging out with radical queers.)

Since Mass moved in last summer, she's been brainstorming ways to make HOWL more appealing to a younger set.

Her long-term vision is to build some new structures on the property — "maybe some tiny houses, some yurts" — and start a queer farming collective. But to ensure that HOWL survives long enough to see its goldenrod-thicketed hillsides dotted with eco dwellings, Mass believes that the community needs to be more visible, which means targeting a broader audience.

"This is a space available for people to do their thing; you can host a writers' retreat, a soap-making class, anything you want," she said. "HOWL should be an incubator for people's ideas."

An incubator requires a functional physical space, and a cozy farmhouse in the woods isn't necessarily cheap to maintain. The $12,000 annual operating budget, which covers utilities, property taxes and basic upkeep, is a fraction of the cost of some major deferred projects — not that cash flow has ever been anything but worrisome, according to HOWL treasurer Lani Ravin. The farmhouse is in immediate need of about $30,000 worth of repairs to the roof and foundation; in the nearish future, the tilting barn will have to be completely rebuilt, a project that Ravin estimates will cost at least $100,000. The whole property, according to its most recent tax assessment, is worth slightly more than $300,000.

HOWL has matching-donation status through several large corporations, including Google and the Home Depot, and Ravin said the collective is working on plans for a capital campaign. Mass told me she likes the idea of a burlesque party-slash-fundraiser in Burlington.

The weekend I visited, Mass' more proximal concern was figuring out how to repaint the kitchen cabinets, currently the color of pus, without inciting drama. In a place like HOWL, whose five collective members weigh in on every major decision, cosmetic changes are never just cosmetic.

"Every single thing in this house has a story," Mass said. "If I wanted to throw away a mug, it would probably be the mug someone used the first time they shared a cup of coffee with the person who eventually became their wife."

Herstory

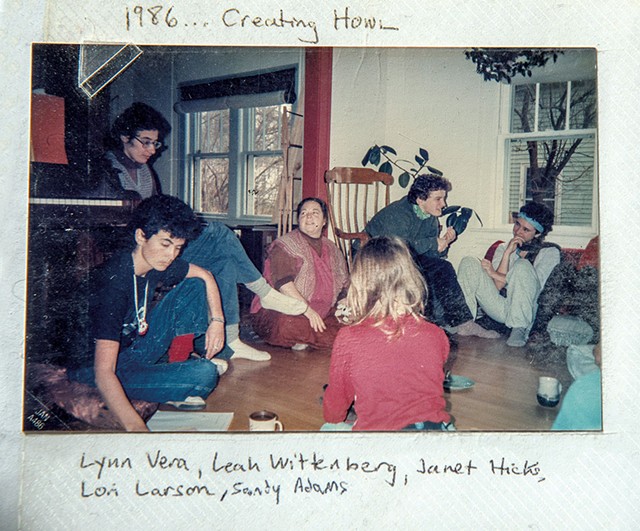

From its inception, HOWL has always been more of a blank canvas than a precisely articulated set of goals. One of its founders, Glo Daley, remains active in HOWL as president of the collective; today, at 79, she's the oldest member of the board and the only one who was around at the very beginning.

"There were a few of us who thought it would be a good idea to have land where you could just hang out naked and not get bossed around by men," Daley told me. "If you look at the smartest animals, they travel in large groups of females. They keep one or two males around just for sperm."

HOWL's founders, who called themselves the Grandmother Council, were predominantly lesbians. But they didn't aim to establish a strictly dyke enclave, unlike some of the more radical separatist factions that sprang up around the same time. These Edens-sans-Adam ranged from women-only music festivals and micropublishing outfits to the Van Dykes, a nomadic troupe of vegan lesbians who, according to a 2009 profile in the New Yorker by Ariel Levy, "shaved their heads, avoided speaking to men unless they were waiters or mechanics, and lived on the highways of North America for several years, stopping only on Women's Land."

Compared to the Van Dykes, the early HOWLers were fairly moderate in their objectives: They sought to create a refuge for all women, regardless of whether they identified as lesbian. In those years, lesbianism signified a political ideology as much as a sexual orientation, a commitment to dismantling the effects of the male gaze. The Furies, a collective based in Washington, D.C., declared in the debut issue of their newspaper that lesbianism was "not a matter of sexual preference, but rather one of political choice which every woman must make if she is to become woman-identified and thereby end male supremacy."

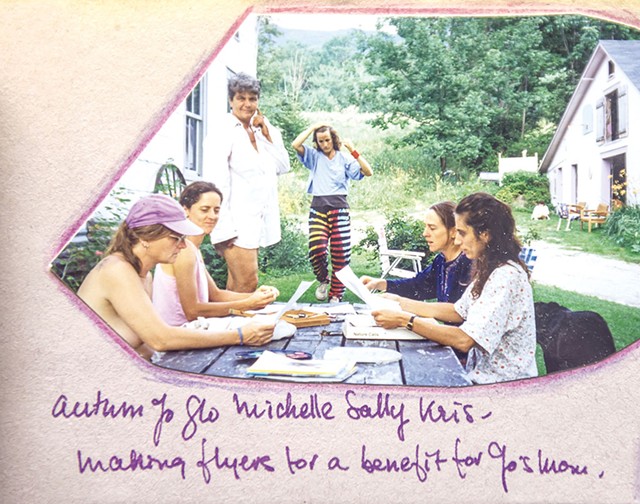

Some of political lesbianism's more zealous adherents decided that the most expedient way to achieve that aim was to create a new spiritual and social order on unspoiled earth. In 1985, an anonymous HOWL supporter purchased a 195-acre parcel at the end of a dirt road in Huntington, with the intention of holding the property until the nascent collective raised enough money to buy a portion of the land. What HOWL's members sought to do on that property, however, was somewhat nebulous from the start. In an April 1986 article in Out in the Mountains, an LGBTQ newspaper published in Vermont from 1986 to 2007, cofounder Alverta Perkins wrote, "A lot of women don't even know what they want from the land yet. They just want the land to happen."

A December 1986 HOWL newsletter offers a glimpse of some of the things that did, eventually, happen: a tepee-raising workshop; a forum on the topics of bisexuality, difference and boy children; and a "no-voice" weekend for hearing-impaired women. In late 1988, after four years of phonathons, fund drives and denied grant applications, the collective managed to purchase 50 of the 195 acres. Shortly thereafter, Daley took up residence in the barn and became HOWL's first caretaker.

In those early days, people came and went as they pleased, doing whatever they felt moved to do on 50 secluded acres with no men around. Daley remembers it as a fearless, heavenly time.

"Just being there was beautiful. We were free. We were at the end of a dirt road. We skinny-dipped in the pond all the time. We weren't afraid of anything. That was back when 'feminist' wasn't a dirty word, but we were tough and willing to do our own thing. Rarely did anything nasty ever happen," she said. She paused a moment to consider. "Maybe someone's cat got devoured once."

Disconnect

click to enlarge

- Karen Pike

- From left: Susan Smith, Lani Ravin, Vicky Tamas, Glo Daley and Anya Schwartz inside the farmhouse at HOWL

In recent years, the word "lesbian" has acquired a passé bluntness within certain circles. A 2016 Slate essay by Christina Cauterucci unpacked its gradual disappearance from the lexicon: "In most young, urban queer communities, at least, lesbian, in its implication of a cisgender woman to cisgender woman ("cisgender" meaning someone whose gender identity aligns with their sex at birth) arrangement, is both inaccurate and gauche," she wrote. Like Cauterucci, my friends and I prefer the more plastic "queer," which reflects a broader range of lived experience and resists the coupling of sexual orientation and gender.

But the transition from "lesbian" to "queer" also represents the erasure of a particular culture. In the same Slate issue, the feminist author and scholar Bonnie J. Morris decried the tacit ageism of de-identification: "The fearless Amazon generation that built an entire network of lesbian music festivals, albums, bookstores, bars, presses, production companies, publications, and softball teams is teetering on the brink of oblivion, just gray-haired enough to be brushed aside with an impatient 'good riddance' by younger activists, yet too recent a movement to enjoy critical historical acclaim."

Lesbian communities, whose existence is largely predicated on a binary understanding of gender, have struggled to adapt to the new queer zeitgeist. In the '70s and '80s, the peak of the women's land movement, some 150 intentional communities were scattered across the country. In 2000, the biennially published Shewolf's Directory of Wimmin's Lands and Lesbian Communities — "wimmin" being one of several variations on "women" that eschew the "men" suffix — listed just 69. In 2015, the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival, an institution on the radical feminist circuit, ended its 40-year run after drawing censure from national LGBTQ advocacy organizations for its policy of excluding trans women. Perhaps most tellingly, Olivia Records, once a thriving production label dedicated to promoting dyke counterculture through music, has pivoted to marketing cruises and resort vacations for lesbians.

This paradigmatic shift has contributed to the steady decline of physical spaces for queer women. In Burlington, where you can't swing a bundle of sage without smudging half a dozen dykes, there hasn't been an official lesbian bar since 135 Pearl closed in 2006 — because, at least in theory, we no longer need that kind of cloistered intimacy when we can be out and proud in almost any establishment.

But 52-year-old Jewels, who was visiting HOWL the weekend I was there, said that greater mainstream acceptance has made her feel invisible to both the lesbian and non-lesbian public. Jewels primarily lives in her green Chevy Express van with her feline companion, Little Buddy, but she occasionally spends periods of time in Burlington; recently, she did a stint as HOWL's caretaker. Over the years, particularly in and around Burlington, she's detected a troubling lack of mutual recognition within the gay women's community.

"There used to be this special handshake when you saw another dyke on the street — just a look, like, 'I see you,'" she said. "Now, we don't acknowledge each other."

The idea of queerness — summed up by Cauterucci as everyone "not cis straight men" — contains a world of identities so vast that most attempts to organize around it tend to collapse on themselves. In 2017, the Winooski gay bar Mister Sister shuttered after just five months amid outrage over its name, a slur used to denigrate trans women. The controversy underscored a larger cultural reckoning: the growing sentiment that any space designated as queer, female-centric or both has a moral imperative to encompass, or at least not blatantly exclude, all identities and marginalized voices.

Where physical spaces have failed to meet the needs of the entire LGBTQ community, not just its white, cisgender ones, online communities have tried to fill the void. In 2015, a group of University of Vermont alumni founded the Facebook group Sensi-Babeington to provide virtual space for anyone who identifies as queer, female, trans or nonbinary, the term for people whose gender identity falls outside the male-female dichotomy. Before joining, potential members are asked to fill out a questionnaire affirming their commitment to prioritizing the needs of queer and trans people of color. But Jas Wheeler, a former Sensi-Babeington moderator, recently decided to leave on the grounds that the group was falling short of its mission.

"With virtual spaces I've found that there's some real difficulty around actually like *prioritizing* queer and trans people," Wheeler wrote in a Facebook message. "I became tired and overburdened by the tasks of modding an online space that is still figuring out how they're trying to prioritize people. Specifically, white cishet [cisgender heterosexual] women in that group are hella entitled and feel like they're able to talk out their neck wild to black and brown people. That's not my ministry."

The denizens of women's lands were — and still are — predominantly white, with access to transportation and the means to support themselves while living off the grid. Modern schools of queer feminist thought, which emphasize intersectionality, have criticized the movement's colonial overtones and appropriation of indigenous traditions.

Both the women's liberation and gay rights movements have historically been fraught with racism and exclusivity. Trans women of color played a pivotal role in the 1969 Stonewall riots, the landmark protest that sparked the gay rights movement in America. But many of the second-wave feminists who staked out land for their penis-free utopias, including some of HOWL's founders, have refused to recognize that trans women are, in fact, women.

A Farmhouse Divided

All five HOWL board members are white; one is trans. According to Ravin, HOWL's treasurer, the collective supports the inclusion of trans women and nonbinary individuals. But the organization's public-facing verbiage doesn't always convey that message. The HOWL website, for instance, proclaims that the land is open to "anyone who identifies as a woman, regardless of assigned gender at birth," which would seem to exclude those who identify as something other than categorically female.

When Meg Mass moved into the farmhouse this summer, she posted a sign on the front door stating that all queer, trans and nonbinary people are welcome. Ravin told me that the collective is working on a new description that will specifically address the nonbinary question.

Part of the lexical disconnect is generational. The youngest board member, Michele Grimm, is in her early fifties. The collective has been actively seeking new members, but recruitment is difficult, said Ravin: "It's the equivalent of getting someone to commit to joining the board of an organization that needs a lot of help." When Ravin joined HOWL a decade ago, the collective consisted of about 10 people, some of whom lived on the land. These days, none of the five board members resides at HOWL.

Mass isn't officially part of the collective, but she gets to weigh in on its management — and, as a representative of a slightly younger generation, she's more attuned to recent cultural shifts in terms of gender and identity. For older HOWLers, in particular, Mass noted, this new landscape can feel like a referendum on their life's work.

"Sometimes, I think, it can be hard for them to hear that something needs to change, but the fact that we need to change doesn't mean that what they did is irrelevant," she said. "It's not about undoing their work but building upon it. At this point, we need to evolve in order to stay alive."

Not everyone has embraced this evolution. A HOWL founder and former collective member, who requested anonymity for fear of being pilloried for her views, told me that about seven years ago, the board began to discuss opening the land to trans women. Ultimately, those conversations became a breaking point in her relationship with the group.

"As a sexual-assault survivor, my view is that it should be a sanctuary for women born women," she said. "But that's not really the latest liberal popular view."

Seventy-six-year-old Stephie Smith, the most recent addition to the HOWL board and its sole trans member, said she's never experienced any pushback or ill feeling from anyone in the collective. She feels that the major bone of contention within HOWL right now isn't so much the inclusion of trans women, but adapting HOWL's governing principles to encompass people who identify as nonbinary.

"We had two board meetings dedicated entirely to discussing whether we should allow nonbinary people at HOWL," Smith said. "Some people on the collective are very intense about this issue, and they want to come up with a rule about it. I think that's a waste of time. I think HOWL is women's land, and we don't need to go any further than that."

In Smith's opinion, the idea of "women's land" is more philosophical than literal. "What matters is that, if you're here, you're not disrespectful or obnoxious," she said.

Daley, for her part, struggles to reconcile the concept of nonbinary-ness with what she views as the original intent of HOWL. In fact, this whole world of gender fluidity doesn't make much sense to her at all.

"I want to be kind to everybody, but I'm not too keen on this movement of people saying what sex they are and changing it back and forth," she said. "I don't even know the language, but I know it's not nature. I grew up as a tomboy. You couldn't put me in a pink dress, but I was free."

But Daley has been willing to yield to consensus, which has tilted decisively toward opening up to all self-identified women, regardless of gender at birth.

"One of my favorite teachers, Pema Chodron, says you can never know what happens next. I'm not going to be around much longer. If the rest of the group wants to do this, they can go ahead, and if HOWL turns into something else, that's the will of the people running it," Daley said. "But I still have to fight against testosterone poisoning, against males running the show. It's not good for the planet, or for us."

Smith, on the other hand, thinks gender is precisely the problem, the source of most hang-ups and discontent. But where would women's land belong in a world without distinct notions of femaleness and maleness?

"I really don't know," she said. "But I won't be around to see it."

Togetherness

As a species, we crave togetherness, even in its complicated and occasionally unpleasant permutations. In recent years, that yearning has taken on a political valence, especially within the LGBTQ community — a search for refuge from the frequently loathsome antics of white, cisgender, heterosexual men. That extends particularly to the one in the Oval Office, who has openly talked about grabbing women "by the pussy" and denied allegations of sexual assault by dismissing the accuser as not his "type." The sense of progress following the U.S. Supreme Court's 2013 decision protecting gay marriage has dissipated in the face of a new crop of conservative-leaning justices, who, later this year, will decide whether an employer has the legal right to fire someone for being openly gay or trans.

Contrary to the media naysayers, Ravin feels that the political climate has reignited interest in places like HOWL. The collective doesn't track visitor numbers, but Ravin said that she has recently witnessed a greater sense of urgency, a desire to align with the anti-patriarchy movement.

"There are attacks on women's rights from all around, and people are waking up," she said. "Anyone who's being oppressed can come to HOWL and be empowered. HOWL is a place to regenerate. I don't see it as a respite but as a model — a safe, inclusive, intersectional alternative to the patriarchy."

For those of us who grew up on the internet, a place like HOWL can feel like a revelation, a wonderland of spontaneous interaction and syrupy late-afternoon light. The privacy curtain in the outhouse is a rainbow flag; the reading material beside the composting toilet is the latest issue of Lesbian Connection. In a cultural moment when the aura of feminism has been deployed as a marketing conceit to sell everything from period-proof underwear to overpriced coworking space memberships, HOWL is thrillingly disinterested in cultivating a brand.

As one of our workshop activities, we drew pictures of the dreams we'd had the night before, then asked each other very gentle questions about them ("Do you think there's some possibility that the figure you're chasing represents some version of yourself?"). Afterward, we took turns performing interpretative dances on the theme of the dream under review (mine: anxiety, elegantly portrayed by Magenta, who just stood there, stiff as a board). The whole exercise felt both pointless and deliriously nice, like a good head rub with one of those Brookstone wire massagers. Politically, we accomplished nothing, but watching three strangers mime my innermost state of being was its own woo-woo reward.

click to enlarge

- Karen Pike

- Meg Mass (left) and Anya Schwartz visiting the Grandmother Tree, a sacred space on the property

On Saturday afternoon, as we lounged around the farmhouse living room after a miscellaneous lunch of bread and all the spreadable substances we could find in the communal fridge, two squeaky-cute young queers arrived. They had driven up from Worcester, Mass., to see Big Thief play at Higher Ground in South Burlington. When they reserved a campsite at HOWL through the online platform Hipcamp, they said, they had no idea that HOWL was a lesbian paradise. As soon as they entered the room, the mood became noticeably bouncier, as if we'd all taken a hit from a helium tank — a side effect of being surrounded, in three dimensions, by other queer people.

Later that evening, we sat around a campfire as Lisa Scanlon, the workshop leader, read aloud a passage from Estés' book that admonished women to respect their bodies by not dietetically diminishing or surgically altering them. Twenty-eight-year-old Lily Fender, visiting for the weekend from Boston, made a disapproving noise. "That's kind of transphobic," she said.

We discussed the consequences of the notion that feminine power resides in a particular body shape, which everyone agreed was bogus. Then, we did something called "authentic movement," which entailed weaving around one another in a sort of manic square dance, extending our arms skyward, sinking to our knees and, finally, prostrating ourselves on the ground. As I lay on my stomach, my right cheek smushed into the damp grass, I overheard perhaps the most lesbian-commune sentence ever uttered: "I'm going to move your chaga mushroom, if that's OK."

While we were all prone, diffusely illuminated by a cloud-covered moon, Scanlon suggested we do a "wonder circle." This involves, apparently, saying aloud the first semi-baked question that enters your mind, the cumulative effect of which makes you feel stoned beyond belief. (I haven't been the same since Magenta opened this can of worms: "How hungry was the first person to figure out how to eat lobster?")

Eventually, we peeled ourselves from the bosom of Mother Earth and huddled around the fire. With a twinge of panic, I grasped what was coming next: We were going to go around the circle and sound our barbaric yawps. For 28 years, I had managed to avoid unleashing a primal scream in the presence of others, and I was somewhat invested in keeping it that way.

Up until the second I opened my mouth, I told myself I was just going to emit a little primal screamlet. And then I thought, Fuck it. I screamed. This was HOWL, after all. If I couldn't lean in to screaming on a hilltop under an almost-full moon, surrounded by queer women, I don't know what I can possibly commit to.

The next day, I hiked Camel's Hump with Fender, who had recently downgraded from an iPhone to a bricky LG flip phone as part of a larger effort to escape the tyranny of constant connectedness. She told me that she had learned about HOWL after reading the New York Times article this past summer, and her initial plan had been to scout it out as a potential camping location for her friend's queer hiking group. But over the course of the weekend, she'd begun to entertain the idea of a farming stint at HOWL after her seasonal gardening job ends later this fall.

"I think this place could be so incredible," she said. "But would my nonbinary or trans friends feel comfortable here? I don't know. I can't speak for them, or for anyone."

The original print version of this article was headlined "HOWLing at the Moon | A women's collective in Huntington grapples with a gender-fluid future"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Culture, LGBTQ, Huntington Open Women's Land, HOWL, Gender

More By This Author

About The Author

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Speaking of...

-

Q&A: Exploring the Haskell Free Library & Opera House With Hannah Miller

Mar 13, 2024 -

Video: Hannah Miller Visits the Haskell Free Library & Opera House in Derby Line, Vt., and Stanstead, Québec

Mar 7, 2024 -

Q&A: A Clinic Has Cared for Old North End Pets for Almost 20 Years

Jan 31, 2024 -

Video: The Old North End Veterinary Clinic Has Kept Costs Low to Help Pets in Burlington for Almost 20 Years

Jan 25, 2024 -

Hey Bub, Citizen Cider's New Light Beer, Brews Trouble With Staff

Sep 25, 2023 - More »

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 3. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 4. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 5. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, April 24-30 Magnificent 7

- 6. Welch Pledges Support for Nonprofit Theaters Performing Arts

- 7. Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April Stuck in Vermont

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse